Right of Confrontation in Sex Cases

David Savage reports that,

The Supreme Court justices, with the exception of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, sounded Monday as if they were likely to bar prosecutors from using in court the words of alleged crime victims who speak to authorities but later refuse to testify. Such a ruling would greatly strengthen the right of defendants to “be confronted with the witnesses against” them, in the Constitution’s words. However, it would be a major setback for victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, who often are afraid to testify against their abusers.

We have a potential 8-1 decision consistent with the Constitution, that follows centuries of tradition, and that preserves the rights of those accused by the state of the most reviled of all crimes. So, what’s the problem?

“The practical reality is many women are scared to death” to testify against a spouse or partner who abuses them, said Ginsburg, now the only woman on the high court. In other instances, “they are so desperate financially” that they decide against testifying, she said. She questioned whether the Constitution should be interpreted to bar prosecutors from using their calls to a 911 line. “This is not just a call. It is a cry for help,” Ginsburg said.

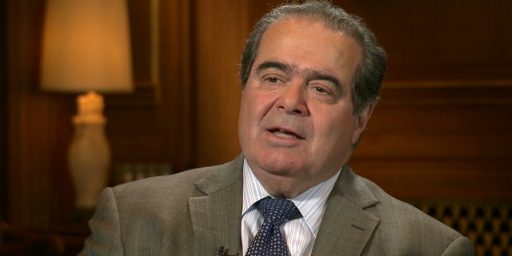

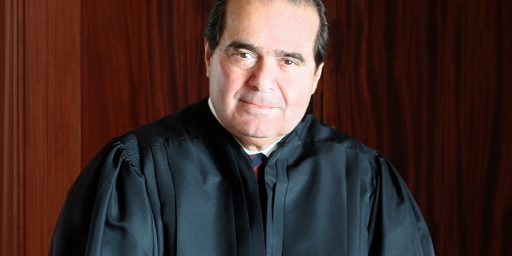

But Justice Antonin Scalia countered that the use of such statements in the place of a witness’ testimony in court violated the principle set in the Constitution. The 6th Amendment says: “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right … to be confronted with the witnesses against him.” Scalia said the court should enforce that right.

“I think the Founders believed in a system where the accused had a right to confront his accusers in court,” Scalia said. “I can’t see why it makes any sense” to allow a taped 911 call in place of a witness’ actual testimony, he said. Under that approach, a defendant loses the right to contest the statements of his accuser, Scalia said.

An ambivalent Kevin Drum responds,

Now, Ginsburg might be right and she might be wrong. But the point is that she was the only one to even raise an argument for allowing the 911 call to be used, and that’s almost certainly because she’s a woman herself and a former director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project. Without her, there apparently wouldn’t have been even a single justice willing to give much weight to the real-world reasons that make it difficult to get victims of domestic violence to testify. Ginsburg’s argument might not be enough to change the result of the case, but it’s something that the male justices should at least be forced to consider.

That’s why they took the case, presumably. It’s just that the plain meaning of the Constitution is in the way of adopting Ginsburg’s view.

While I have a reasonable grounding in Constitutional Law, my background on evidentiary rulings is minimal. I understand that there are exceptions to the strict requirement that a defendant must be able to confront witnesses. FindLaw outlines them. Some of them are rather obvious. If a defendant caused the witness not to be able to appear in court, for example by murdering them, declarations they made previously are often admitted into evidence.

More controversially, the courts have dealt with the issue that Ginsburg addresses: the fear and social stigma attached to victims of sex crimes.

Contrasting approaches to the Confrontation Clause were taken by the Court in two cases involving state efforts to protect child sex crime victims from trauma while testifying. In Coy v. Iowa, 173 the Court held that the right of confrontation is violated by a procedure, authorized by statute, placing a one-way screen between complaining child witnesses and the defendant, thereby sparing the witnesses from viewing the defendant. This conclusion was reached even though the witnesses could be viewed by the defendant’s counsel and by the judge and jury, even though the right of cross-examination was in no way limited, and even though the state asserted a strong interest in protecting child sex-abuse victims from further trauma. 174 The Court’s opinion by Justice Scalia declared that a defendant’s right during his trial to face-to-face confrontation with his accusers derives from ”the irreducible literal meaning of the clause,” and traces ”to the beginnings of Western legal culture.” 175 Squarely rejecting the Wigmore view ”that the only essential interest preserved by the right was cross-examination, 176 the Court emphasized the importance of face- to-face confrontation in eliciting truthful testimony.

Coy’s interpretation of the Clause, though not its result, was rejected in Maryland v. Craig. 177 In Craig the Court upheld Maryland’s use of one-way, closed circuit television to protect a child witness in a sex crime from viewing the defendant. As in Coy, procedural protections other than confrontation were afforded: the child witness must testify under oath, is subject to cross examination, and is viewed by the judge, jury, and defendant. The critical factual difference between the two cases was that Maryland required a case-specific finding that the child witness would be traumatized by presence of the defendant, while the Iowa procedures struck down in Coy rested on a statutory presumption of trauma. But the difference in approach is explained by the fact that Justice O’Connor’s views, expressed in a concurring opinion in Coy, became the opinion of the Court in Craig. 178 Beginning with the propo sition that the Confrontation Clause does not, as evidenced by hearsay exceptions, grant an absolute right to face-to-face confrontation, the Court in Craig described the Clause as ”reflect[ing] a preference for face-to-face confrontation.” 179 This preference can be overcome ”only where denial of such confrontation is necessary to further an important public policy and only where the reliability of the testimony is otherwise assured.” 180 Relying on the traditional and ”transcendent” state interest in protecting the welfare of children, on the significant number of state laws designed to protect child witnesses, and on ”the growing body of academic literature documenting the psychological trauma suffered by child abuse victims,” 181 the Court found a state interest sufficiently important to outweigh a defendant’s right to face-to-face confrontation. Reliability of the testimony was assured by the ”rigorous adversarial testing [that] preserves the essence of effective confrontation.” 182 All of this, of course, would have led to a different result in Coy as well, but Coy was distinguished with the caveat that ”[t]he requisite finding of necessity must of course be a case-specific one;” Maryland’s required finding that a child witness would suffer ”serious emotional distress” if not protected was clearly adequate for this purpose. 183

In another case involving child sex crime victims, the Court held that there is no right of face-to-face confrontation at an in- chambers hearing to determine the competency of a child victim to testify, since the defendant’s attorney participated in the hearing, and since the procedures allowed ”full and effective” opportunity to cross-examine the witness at trial and request reconsideration of the competency ruling. 184 And there is no absolute right to confront witnesses with relevant evidence impeaching those witnesses; failure to comply with a rape shield law’s notice requirement can validly preclude introduction of evidence relating to a witness’s prior sexual history. 185

The bottom line, though, is that the accused’s rights to confront his accuser in a manner that allows the jury to judge the demeanor of said accuser is paramount. A 911 call might be quite compelling but lacks a visual component. For all the jury knows, it could be staged by a spiteful ex-lover. It is harder to lie in open court than via telephone.

The irony here is that it is the liberal Justice (and blogger) taking the side of the accuser while the conservative Justice (and blogger) are taking up for the rights of the accused.

This is a prime example of the what the constitution “ought to” vs “does” say. For those who are outraged at this decision, start a campaign to get an amendment. Do the heavy political lifting to get the amendment passed. And then I suspect that you would find a 9-0 decision in your favor. The constitution is a “living document”, but changes should be thought out, debated, and voted on by those who are answerable to the electorate. Change should not come at the whim of five unelected people.

re: yetanotherjohn

I wish more people understood that point. Too many Americans want to change the constitution by putting activist judges on the bench and thus eventually surrender their rights to a ruling elite – the judiciary.

Do not change the court, change the law.

Yeah, we’re all shocked that Scalia took the wife-beater’s side.

Hey, someone had to say it. (and I was kidding! Relax!)

kevin drum’s remarks are a sexist embarassment

“The irony here is that it is the liberal Justice (and blogger) taking the side of the accuser while the conservative Justice (and blogger) are taking up for the rights of the accused.”

I consider myself a conservative, and I often take up the side of the accused. The Constitution stands on the side of the accused lest there be star chambers.

RJN: Exactly right. And I think liberals and conservatives generally agree on that, actually. But, since the most aggregious decisions of the Warren Court, conservatives have fought against judges letting the guilty off on “technicalities.”

In this case, though, respect for the law outstrips that for consequences. And I suspect Scalia has no more sympathy for rapists than Ginsburg.

I think there is a difference between granting constitutional rights and letting people go on technicalities. For the first, saying the constitution grants a right and thus we should afford the right to the accused is just enforcing the constitution as written. The second starts with a constitutional right and then fashions a remedy that is beyond the constitutional rights scope. As it stands now, if I gather enough explosives to bring down a large building complete with plans and timetable, kidnap a dozen young elementary girls for a sex harem and the tanned hides of a half dozen endangered species and the police discovers this because of an improperly prepared search warrant, all of that evidence may not be returned to me, but it would be fruit of the poisoned tree and can’t be used against me. That requirement is not in the constitution. For example, the evidence could be used in prosecuting me for the crimes, but I could be monetarily recompensed for the government’s violation of my constitutional rights.