435 Representatives: Unconstitutional?

Is Congress too small and unequal to do its job?

Is Congress too small and unequal to do its job?

The U.S. House of Representatives is the same size it was a century ago — even as the country’s population has grown more than three times as large.

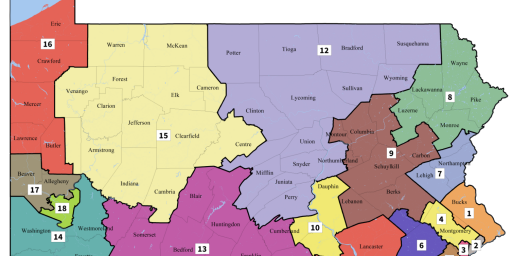

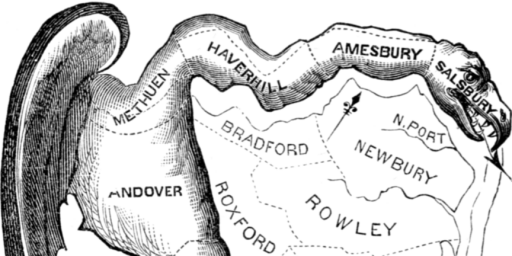

That’s resulted in growing disparities between the largest congressional district and the smallest. When the U.S. Census Bureau releases state-by-state population numbers this month, it’s likely that Montana’s lone congressional district will have about 450,000 more people in it than that of its Wyoming neighbor.The U.S. Supreme Court could decide as soon as today if justices will hear a case on whether those disparities violate the principle of “one man, one vote.” Justices were scheduled to discuss the case behind closed doors Friday.

The lawsuit, Clemons v. U.S. Department of Commerce, seeks a court order to force Congress to add more members so that the sizes of congressional districts would be more equal.

Last July, in a decision that quoted liberally from the Founding Fathers, a special three-judge panel ruled against changing the current system. “We see no reason to believe that the Constitution as originally understood or long applied imposes the requirements of close equality among districts in different states,” it ruled.

Our own Dave Schuler frequently argues that the current scheme is not representative. And he’s doubtless right: The average Congressman has over 700,000 constituents. How much does he actually care about their interests? How likely is he actually to meet most of them face-to-face?

When districts are that large, the likeliest outcome is that the Representative will pay most attention to the organized interest groups who lobby him and donate money to his re-election effort. At best, this is representation once removed.

And that assumes that the district is politically competitive to begin with. In too many cases, the lines are drawn with the specific intent of stacking the deck in favor of the incumbent or his party. At that point, there’s not really any representation to speak of.

All that said, however, the lawsuit is about a different question: Does a fixed size of 435 Representatives violate the Supreme Court imposed requirement of equal representation — the One Man, One Vote principle of Baker vs. Carr?

I don’t see how. The Framers mandated that each state have at least one Representative and that “the number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every 30,000 persons.” So, there was always going to be a disparity.

via Glenn Reynolds

Nor did they mandate that there be one representative for every 30,000 persons. Good thing, too, since we’d need 10,333 Representatives to meet that number.

There’s a practical limit to the size of a working legislative body. It’s probably higher than 435 but it’s certainly much less than 10,333. The smallest state has roughly 500,000 people. Using that as the guide, we’d have 620 reps. If we went down to 250,000 — which would be a significant improvement in representation over present — we’d need 1040. That’s an awfully big legislature.

There is a point at which a difference in degree is a difference in kind. One district having 50,000 voters while another has 60,000 voters? Not a big problem. One district having 250,000 voters while another has 750,000 voters? Problem.

Much of the criticism of a larger House appears to be along the lines of “it’s hard to get to know the other representatives”. Congress isn’t a work group; it’s a representative body. Congressional representatives aren’t supposed to get to know their colleagues, they’re supposed to get to know their constituents.

This isn’t the 18th century. Our modes of communications are enormously more varied and capable. There isn’t even a real need for Congress to meet, physically, any more. They can and should teleconference.

To my mind a better criticism of a larger House is that it would give even more influence to lobbyists. If I were king, I’d prohibit lobbying of House members except by constituents. Coupled with a significantly enlarged House I think that could reduce the influence of paid lobbyists by making it cost prohibitive.

This is coming late to the fore, however, if nothing is done about gerrymandering we could see a further developement of a “slave class”. Whatever happens, the concentration of populations in cities seems to inevitably lead to a loss of individual liberty. Illinois is a clear case in point of a city running roughshod over the interests of small towns and rural areas.

Like a tumor on an otherwise healthy organism, cities suck the life, liberty and treasure out of the dispersed populations. Of course it can be argued that they have the right to do so, but what tumor cell wouldn’t make such an argument?

Properly districted and represented we could hardly do with less than 1500 representatives given one for each 200,000 people.

The real solution might simply be to leave it at 435 and disseminate the power back to the local level and let the local people decide what to have for lunch.

Rising to the defense of the state in which I reside, I don’t think it’s quite that simple, floyd. Chicago may be politically dominant in Illinois but it’s economically dominant, too. Although much of Illinois’s spending goes to Chicago and its collar counties a higher proportion of its revenue comes from the same area.

If Chicago and its collar counties were to suddenly vanish, it wouldn’t be all skittles and beer for Illinois’s small towns and rural areas. They’d be even poorer than before.

Dave;

I too have the misfortune of being an Illinois resident, and while there is some legitimacy to your view, in aggregate I must disagree. Then… there are at least two sides to every story.

Much of the criticism of a larger House appears to be along the lines of “it’s hard to get to know the other representatives”. Congress isn’t a work group; it’s a representative body. Congressional representatives aren’t supposed to get to know their colleagues, they’re supposed to get to know their constituents.

It’s both. While there are definitely arguments to be made in favor of having representatives closer to their constituents and while I am attracted to the NetConferencing legislative model, the biggest issue with 6,000 representatives (to pick a number from Doug’s post) is the lack of structure that would be required. Being a representative is not just about voting on issues. It’s about proposing legislation that you have a reasonable idea will pass.

That’s not to say that this couldn’t work itself out, but it’s absolutely an issue that needs to be addressed. Having 6,000 legislators makes it hard to coordinate to draft bills. You’d need the bills to be primarily written the in Senate (which is problematic in its own way) or you would need to radically redesign the way that bills are proposed and written, possibly resulting in everybody having a corner representative but with a more rigid leadership structure to filter and draft bills. The corner representative may get to vote, but he would have to be in congress for numerous terms before he could actually affect the laws being written.

When districts are that large, the likeliest outcome is that the Representative will pay most attention to the organized interest groups who lobby him and donate money to his re-election effort. At best, this is representation once removed.

And that assumes that the district is politically competitive to begin with. In too many cases, the lines are drawn with the specific intent of stacking the deck in favor of the incumbent or his party. At that point, there’s not really any representation to speak of.

https://www.outsidethebeltway.com/435-representatives-unconstitutional/

This is exactly backwards. A district that is drawn with a distinct partisan bent is one in which a representative must support the general interest or risk a primary challenge. In a district which is “competitive” the representative has no general interest to represent and therefore no reason to do anything but cater to organized interest groups. In all the clamor for competitive districts people forget that partisan affiliation is a basic political choice that individuals make, and it is a good proxy for actual shared representative interests at the local level. A district which has no logical functional coherence, geographically and in terms of shared interest is one that is most at the mercy of outside organized interest groups with resources.

Forgot the final paragraph.

The larger a district is, the less likely it is to be coherent both in terms of geography and actual shared interest, so a balance is required. Violating either one too much causes problems.