9-9-9 and the Institutional Structure of the US Government

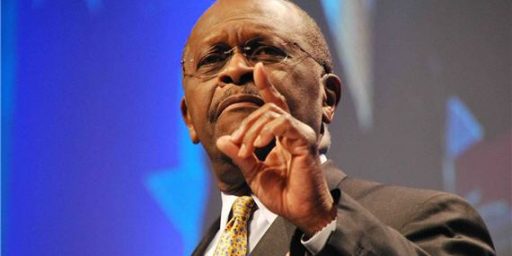

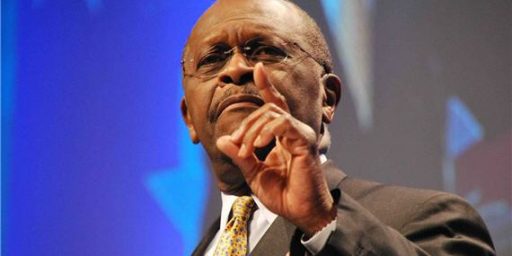

If you are taking 9-9-9 seriously, then you don't understand the way the US government works. Herman Cain, I am looking at you.

Note: this piece fits into an irregular series that addresses the question of the role of institutional parameters in explaining political outcomes int he US. The first in the series was here: Are our Problems Based in Leadership or Institutions?.

The US political system simply does not allow for even the possibility of bold political proposal like Herman Cain’s 9-9-9 proposal. Forget for a moment about the merits of the proposal and concentrate on the significance of both a candidate who would campaign as if the plan is, in fact, politically feasible as well as supporters who would base following said candidate on the basis of such a plan.

I was listening to an excerpt (here) of Cain explaining his 9-9-9 plan in a radio interview and was struck by the sheer impossibility of accomplishing even a fraction of what he was proposing. As an evaluation of the candidate, the 9-9-9 plan indicates one (or some combination) of the following: Cain is a pie-in-the-sky idealist, an utterly cynical opportunist, or a person who simply does not understand the way the government works. In honesty, based on Cain’s views of governance, such as the importance (or lack thereof)of knowing stuff about foreign policy, I have to go with the last option as the most likely fit.

Beyond the candidate, this type of scenario (i.e, a candidate running on an utterly impossible platform) gets to a major problem in US politics: most of us really do not understand the complexities of the legislative process and, therefore, many are too willing to assume that a given president can actually be elected and then implement the policies that the candidate is promising. When it comes to domestic policy, this is manifestly not the way it works and even in foreign policy, where the president has a lot more leeway, it is never as easy as it looks. It is also why we are so frequently disappointed by presidents once elected.

By way of explanatory contrast, if we had a parliamentary system, wherein the party (or coalition of parties) that won the majority in the legislature could implement their policy vision, then the leader of that party could credibly campaign on a bold policy agenda. Because, of course, the only way to become the leader (and presumptive prime minister) is to have support of the party as it is. But of course, we have a system of separated powers wherein the executive and legislative branches have to negotiate one with another to achieve policy outcomes. This reality puts the notion of bold policy initiative into the rare, if not impossible, category.

Consider the following institutional facts about our system that utterly mitigate against a correlation between what a presidential candidate bases a campaign and what that president can deliver if elected, policy wise:

1) Presidential candidates are chosen by citizens adhering to a given party (through the labyrinthine caucus/primary process) and therefore their policy preferences do not necessarily reflect the policy preferences of the legislative manifestation of their party.

2) The president has only influence, not control, of the legislative agenda. While the president does have avenues to influence what is discussed in Congress, the bottom line remains that the actual agenda (from the committee level, to the legislative calendar, to the floor and beyond) are wholly out of the control of the president. Even if the president’s party controls either or both chambers, the ability of the president to control the process is nil. In other words: no member of congress takes orders from the president. The relationship is in no way hierarchical.

3) A list like this, of course, cannot ignore the additional level of complexity added to legislating that bicameralism introduces (passing a bill through two institutional actors is, by definition, harder than through one). And, of course, the Senate adds a plethora of other complexities, including constitutionally baked-in over-representation of numeric minorities, but also the fact that the chamber has become, for all practical purposes, a super-majority (60%) vote chamber for most business.

All of the above is not, by the way, a call to reform, but rather is a call to understanding both in terms of how the US government actually works as well as how to evaluate the probability of the claims of a given candidate.

It would be interesting, not to mention better for the country, if we ran presidential campaigns (both in terms of the behavior of the candidates and the media coverage thereof) with these types of things in mind. However, we instead tend to have campaigns wherein candidate run as political messiahs (in the sense that there election will somehow be transformative of politics in Washington) or, at a minimum, revolutionary leaders who will “take the country back.”

This is a helpful and insightful argument on the basis of how our government works. You are right on the subject of how the president is viewed by the masses and what he can actually do while holding office. Just like many other presidents, the power of the president on domestic issues is very limited in scope especially today. I believe that was the ultimate folly of President Obama’s campaign and presidency since many people were caught onto his “hope” and “change,” but it changed when he became the president. Yes there were mishaps that he has done, but I believe no one has become president with the intention to ruin America.

I disqualify Herman Cain from being President just because of his ignorance of foreign policy, an area that is very important to me.

@Eric: So the logical choice would be Newt, who knows the complexities of both domestic and foreign policy?

The only caveat I’d add is that this is hardly a problem unique to Cain. Barack Obama, for example, ran against a mandate when proposing a health care package in the Democratic primaries, yet ended up signing a bill that included one. And realistically we live in a world where the media demands these plans at a level of detail that no president can deliver on, and pundits (like us) immediately jump on minor details of a plan that, in all likelihood, bears little resemblance to what will end up being put before Congress in the end, rather than treating them as initial negotiating positions, which is essentially what they really are.

@Chris Lawrence:

Good point. But, I think you’re violating the pundit code by revealing our errors 😀

@Chris Lawrence:

Of course, it’s also the politicians fault. They don’t say “This is my initial negotiating position but the final plan will probably look very different.” They say “This is MY PLAN. And, I will get it passed.”

@Pete: I have to admit that I have taken Gingrich seriously earlier. But just because he knows of the complexities of both domestic and foreign policies doesn’t make him the ideal candidate. However, I don’t think that he should be discounted. He has proven that he can go against his party on certain policies (with his criticism of Paul Ryan’s medicare plan, calling it “right-wing social engineering”). But I don’t know who the best candidate for the job, yet. It’s not even a year before elections and we have to make up our minds about who should be the candidates for president right now.

@Chris Lawrence:

Indeed. He was just the proximate inspiration. The dynamic I am describing is probably at least as old as the media age, if not older.

And yes: the media is part of the issue.

I would say this: I don’t think that problem is too much criticism, I think the problem is pretending like a president has control of the legislative process.

@Doug Mataconis: Yeah, but whose going to vote for “this is my initial negotiating position…”? Seriously…

We have a few dysfunctions in our government, and congressional RWARS do constrain evolution, but I think the question of the Presidency is a bit different.

It is probably totally unreasonable to think that one guy should be chief executive for 300 million people, but we go there because that is our nature. We are tribal. We need a chief.

@Eric:

No, “hope and change” exactly what a chief is supposed to promise. And if he doesn’t deliver you throw him in the volcano.

Being a somewhat evolved nation, we only figuratively throw him in, leaving Carter and GW Bush to molder at their respective ranches.

@john personna: So a President has to “deliver” the hope and change? This is not the 1800s and the mid 20th century. Presidents have a lot less power than before and that power has slowly been transitioning to Congress. If a President in 4 short years can change everything and anything about the government, then you have an efficient government, which in the words of Harry Truman, “whenever you have an efficient government, you have a dictatorship.”

@Eric:

You will have to explain that one. The basic institutional configuration is no different now than then,

And, really, modern presidents have more power because of military and foreign policy conditions being quite different in the modern era.

@Steven L. Taylor:

The power that I was referring to was more influence than the “basic institutional configuration” toward domestic policies. During the age of Andrew Jackson, he was really one of the more powerful Presidents in history. The power of influence of Presidents declined when Lincoln was assassinated and his VP Johnson, took over. Congress with the Radical Republicans in charge basically made Johnson insignificant over their conflict of how to deal with the South (they made the military answer to Congress when they set up military states in the South, instead of the President). This trend was kept up until FDR took office and changed the entire face of the US government with his New Deal policies and presidents afterwards with dealing with Communists (that part was more toward foreign policies though). The institutions were the same, but how Congress and the President dealt with each other and who held more “influence” changed periodically.

@Eric:

I’m saying there are things “chiefs” have promised for thousands upon thousands of years.

A good harvest, a good economy, the favor of the gods.

(There is more subliminal mojo here than most will admit.)

Well said. And it would be a terrific frame for a book!

I will add a point on the other side, however: It could be argued that in a party system and congressional-electoral process that makes broad national debate about “bold” ideas highly difficult, presidential candidates who talk as if the presidency really could be a vehicle for major policy change are one of the few ways we can get such conversations in this political system.

So candidates with ideas like 9-9-9 are at least raising something outside the current consensus, and potentially nudging the debate.

No, it has no chance of enactment. And it could also be argued that pie-in-the-sky ideas like this only exacerbate cynicism about our politics, given those vanishingly low prospects for enactment.

I’d, of course, be a lot happier if a candidate would talk about political reform. It may be pie-in-the-sky, too, at least in the short run, but it’s the conservation we need, as this post shows.

@MSS:

Indeed!

Indeed. At this point I think that before we even get to that point the public has to understand that their frustration is not a function of failure to pick the right president (or, for that matter, even members of Congress) but is baked into the system. But we are in basic agreement there, I think.