A Home Is A Lousy Investment (Unless You Need A Place to Live)

Two economists look at a 30 year investment in a home versus putting the same money in the stock market.

USC economist Robert Bridges takes to WSJ to explain why A Home Is a Lousy Investment.

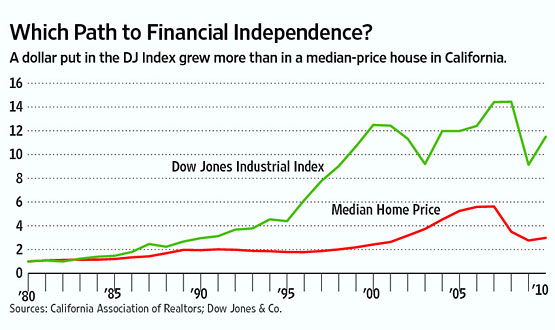

Between 1980 and 2010, the value of a median-price, single-family house in California rose by an average of 3.6% per year—to $296,820 from $99,550, according to data from the California Association of Realtors, Freddie Mac and the U.S. Census. Even if that house was sold at the most recent market peak in 2007, the average annual price growth was just 6.61%.

So a dollar used to purchase a median-price, single-family California home in 1980 would have grown to $5.63 in 2007, and to $2.98 in 2010. The same dollar invested in the Dow Jones Industrial Index would have been worth $14.41 in 2007, and $11.49 in 2010.

Here’s another way of looking at the situation. If a disciplined investor who might have considered purchasing that median-price house in 1980 had opted instead to invest the 20% down payment of $19,910 and the normal homeownership expenses (above the cost of renting) over the years in the Dow Jones Industrial Index, the value of his portfolio in 2010 would have been $1,800,016. The stocks would have been worth more than the house by $1,503,196. If the analysis is based on 2007, the stock portfolio would have been worth $2,186,120, exceeding the house value by $1,625,850.

In light of this lackluster investment performance, and in the aftermath of the recent housing-market collapse, why is there such rapt attention to the revival of the homebuilding industry and residential property markets? The answer is that for policy makers whose survival depends on economic recovery, few activities have such direct, intense and immediate positive economic impact as new home construction.

Berkeley economist Brad DeLong points out that Bridges made a wee omission in his calculation:

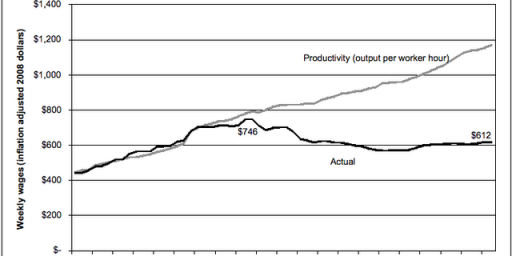

First of all, you get to live in a house. You don’t get to live in your Dow-Jones Industrial index. The choice is not between investing $99,550 in a house from 1980 to 2010 and investing the same amount in the DJIA: it is between:

- Investing $99,500 in a house in 1980 and selling it in 2010

- Investing $99,500 in the DJIA in 1980, and paying rent each year–a rent of $5000 per year at the start, rising gradually to $15,000 per year.

If you have to take the rent out of your DJIA account every year, your dollar invested in the DJIA grows to only $3.42 by 2010–not $11.49.

If you invest your money in the same kind of home that you would live in anyway, the long-run historical record shows that residential housing and equities deliver roughly equal returns as asset classes once you take account of the fact that you get to live in your house.

Now, this only works if you actually live in your house for 30 years. If you move every few years, you’ve got to factor in realtor commission and various loan and preparation fees and the inconvenience of needing to unload the house. And there are not insubstantial maintenance costs and the seemingly irresistible impulse to drop a lot of money into upgrades. So, one’s primary residence should be viewed primarily as a home, not as an asset.

That’s pretty much my philosophy with my home. I didn’t by it to make money with it as an investment. I bought it becuase I wanted a solid roof over my head and I was sick and tired of being beholden to landlords. My loan will be paid off 3 months after I turn 65, and I plan to live in the house long after that.

You can beat this with good location. It is the average result, after all. (And of course it follows that you can do much worse with bad location.)

My other comment would relate to “sizing.” Generally we buy bigger than we’d rent. That makes the smaller rental better in economic terms, but of course the bigger house wins as experience and self-reward.

It’s important not to tangle experience and self-reward with investment. The latter is too often used to justify the former.

Yikes, my CAGR has fallen to 4.25%. That is a smidge better than average, but nothing to write home about.

Use these two pages to calculate yours (I’m not implying that you should share the result):

http://www.zillow.com/

http://www.moneychimp.com/calculator/discount_rate_calculator.htm

I have no problems viewing my house as both a residence and an asset, because that’s what it is. It’s not an IRA, of course, but it’s still an asset which I’m investing in. Is a better “investment” than stocks? Probably not.

But it’s a better investment than 30 years of renting.

It all depends on one’s situation, and I think a lot of boils down to how often one is going to move. We bought our current house almost exactly 9 years ago and ended up refinancing our 30 year note to a 15 year note not long thereafter to take advantage of low interest rates. Now, we will have this house paid off right around my 50th birthday (and the odds we are going to move before then is quite slim). This will help allow me to have more cash on hand at about the time I have kids in college. At a minimum, it will be like getting a huge raise as a 50th b-day gift.

Plus, I also know that my monthly mortgage payment is not that much more than a rental on a nice three-bedroom apartment in the same part of town in which I live. Granted, there are maintenance costs and the upgrade issue.

Still, in my case there is zero doubt that buying is a better financial choice than renting.

Your home is an asset in that once it is paid for your housing expenses drop precipitously. And when you are old, you defer maintenance reaping additional rewards.

Flipping it into cash to fund an expensive retirement community living is probably not going to work out. Same with funding your retirement cruise, vacations, etc.

It is an asset – it is not an investment. Or at least not a very lucrative investment. If I back out the man-hours of labor I have in it I’m losing big-time. But I still have a significant amount of equity.

I find it shocking that

Fox Newsthe WSJ would omit a major financial consideration (as pointed out by DeLong) in order to make their argument.@hey norm: I’m not sure why you (and DeLong) are blaming WSJ. They’re publishing a provocative op-ed by an economist at a solid institution; it’s him, not the newspaper, that gets the blame for weak argument.

James, are you really unaware of how fact-challenged the entire WSJ opinion section is?

@mantis: I read articles, not opinion sections or even newspapers. There are publications hackish enough that I’m loathe to read, much less cite, them. I don’t put WSJ into that category.

houses are a depreciating asset…someday a lot of people are going to learn wood rots, appliances break down…

@James Joyner:

The WSJ editorial/opinion pages certainly belong in the ‘hackish’ category.