A “Republic v. Democracy” Lexicon

Concepts, basic applications, and even a bibliography! Merry Festivus, everyone.

Note: this started as part of another post, but it made more sense to just break it out here. Plus, I think I will want to refer back to this specifically in the future.

Terms

Constitution: A written document that outlines the structure of governance in a given country. These came into vogue in the 19th century–prior to that point in time the discussion of a “constitution” meant collected norms and views that dictated governance, but not in written form (the term, in fact, was used by the ancient Greeks, for example, but not in the way we use the term). Indeed, some countries still have unwritten constitutions (e.g., the UK). However, the norm has been for countries, both democratic and not, to write constitution. Having a constitution, does not make a country a democracy, nor does it make it a republic.

Constitutional Monarchy: A country governed by a constitution that also still has royalty. Usually this refers to a case in which there is both representative democracy and a hereditary head of state (although technically, it might not be a democratic constitution).

Constitutional Republic: A republic (see above) with a constitution. It really doesn’t mean much more than that, strictly speaking.

Democracy: Since the late 18th and as developed in practice in the 19th century, this has meant a government founded on the notion of popular sovereignty (power from the people) that consists of elected representatives as differentiated from some other power system, e.g., rule by the rich, rule by the military, rule by the clergy, rule by the aristocracy, etc. It does not mean direct democracy or pure majority rule. It therefore means, in the modern context, representative democracy, i.e., a system wherein voters choose agents to govern on their behalf for set periods of time. The exact nature of how votes become offices varies from system to system. There is an inherent assumption, however, that the goal of any system of representation is to reflect the will and preferences of the people, and that the will of the majority would be given more weight than that of the minority, even while protecting minority rights (more on that below).

In the modern context the idea of “democracy” is one of representation coupled with majority rule for basic governance and substantial protection for human rights, i.e., minority protections. Indeed, the quality of a given democracy focuses on both the degree to which its electoral system captures an accurate representation of the population (i.e., reflects majority rule) and the degree to which is protects minority rights and preferences (i.e., access to rights, privileges, and representation for all members of its society). I cannot stress enough that what I am here describing is true in all the democracies I have names so far in this piece (as well as any others one might care to name).

I should also note that the issue of how well an electoral system represents its population is a major sub-topic here. For example, the US system favors large parties, so small parties (like Libertarians and Greens) have no shot at election. Other countries (a large number, in fact) provide pathways for electoral minorities to still win seats in the legislature (where, however, majority rule applies to decision-making).

Let me underscore again: there is no country in the world worth of being called a “democracy” that does not respect minority rights. A system wherein the majority can vote away the rights of the minority is anti-democratic.

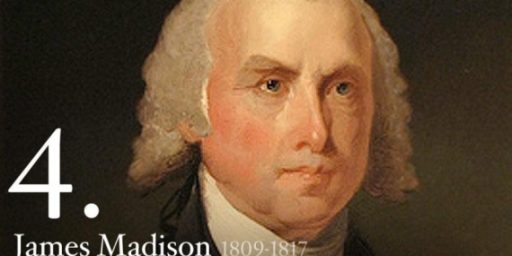

Direct Democracy: A system wherein the people assemble and directly make policy decisions. There are no elections, but rather every citizen is a member of government. This can only happen in very small societies. There is not suitable for governing a country, even a small one like Iceland. (And this is what Madison meant by a “democracy”).

The US, like every other “democracy” in the world, is not a direct democracy.

Majority rule: The idea that when making decisions, the majority preference should have more authority than minority preferences if it is necessary that preferences need to ranked (such as with the passing of legislation or selecting the winners in an election). This comes about as a result of the notion that since all human being should be considered equal (once we dispose of the notion of aristocracy) then how else can decisions be made save to state that if all humans are equal, then each should be afforded that same amount of power.

Minority Protections: The notion that since some human rights are inviolable, that even the will of the majority cannot take them away. The First Amendment of the US Constitution is great example of such protections, as it asserts that no law can be passed (i.e., majority dictate) to remove basic freedoms, such as the right to speak, publish, assemble, or worship. Also: the usage of super-majorities to make decisions, such as is typically the case (but not always) for amending constitutions is a protection of minorities.

Republic: in its most general sense, this just means a system of government where power derives from the people, not an aristocratic class. If one wants to be simplistic, having a republic means not having a monarch. Hence, the UK is not a republic.

There is also a deeper discussion about the Latin roots of the word, and even the way the term was used by Greek and Roman philosophers, but we will leave those aside and stick to basically modern usage. But the whole “no king” this is also why it is not unfair to call The People’s Republic of China and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics both “republics” even though they are decidedly not democracies.

Applications of Terms

So, for example: it would be fair to say that, off the top of my head, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Japan, Sweden, and Spain are not republics, but instead are constitutional monarchies (and, to make matters complicated, NZ and the UK lack written constitutions). They are, however, representative democracies.

Now, some republics would include: Argentina, Brazil, France, Colombia, Chile, Mexico, Peru, South Korea, and the United States. This is because, they have no monarch. These are all, also, representative democracies.

So, it would fair to say, that all the countries listed above are also democracies–because they are all governed by elected representatives, even if they are not all republics. All, too, have constitutions, even though NZ and the UK’s are unwritten.

Suggested Readings

Dahl, Robert A. 1998. On Democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dahl, Robert A. 2001. How Democratic Is the American Constitution? New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dahl, Robert A. 2005. “James Madison: Republican or Democrat?” Perspectives on Politics, 3,3 (September): 439-448.

Elkins, Zachary, Tom Ginsburg, and James Melton. 2009. The Endurance of National Constitutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Kernell, Samuel, ed. 2003. James Madison: The Theory and Practice of Republican Government. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Lijphart, Arend. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries., 2nd edition. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty.

Taylor, Steven L., Matthew S. Shugart, Arend Lijphart, and Bernard Grofman. 2014. A Different Democracy: American Government in a 31-Country Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

For practical purposes Switzerland, with a population of 8 million, has a direct democracy. They call it “direct representation”. It has a bicameral legislature composed of the Federal Council and the Federal Assembly, but any matter of significance is turned over to referendum.

Could direct democracy work in a larger country? Nobody knows. It’s never been tried.

@Dave Schuler: Switzerland does have extensive usage of referenda, but while it is sometimes called a “direct democracy” that description is incorrect.

Perhaps a better way to say it is that Switzerland has more direct democracy elements in its system than do most representative democracies.

@Dave Schuler:

I would think that California typically has more initiatives in a given year than does Switzerland, and its population is five times that of Switzerland.

Incidentally, Switzerland is a republic, with the Federal Council serving as the executive.

When those (often southern conservatives) state that the United States in a “Republic”, somehow alluding to the fact that it was white land owners that had the vote, and by gum we should go back to that…

I bring up the fact that we are a “Democratic Republic” which I have said is a system in which all could vote, but only those that care enough to get off the sofa and vote, rule.

Sadly, the electoral college has proven me wrong now for the 5th time, so…

I, for one, welcome our new Oligarchy.