Supremes Limit Enemy Combatant Detention

CNN (AP)– A mixed verdict on the terror war

The Supreme Court delivered a mixed verdict Monday on the Bush administration’s anti-terrorism policies, ruling that the U.S. government has the power to hold American citizens and foreign nationals without charges or trial, but that detainees can challenge their treatment in U.S. courts. The administration had sought a more clear-cut endorsement of its policies than it got. The White House had claimed broad authority to seize and hold potential terrorists or their protectors for as long as the president saw fit – and without interference from judges or lawyers. In both cases, the ruling was 6-3, although the lineup of justices was different in the two decisions.

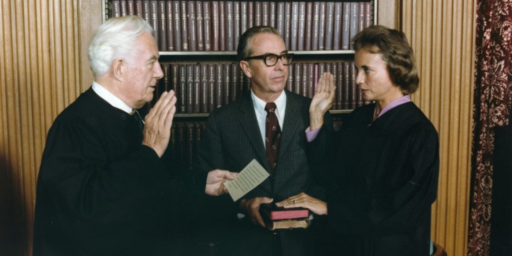

Ruling in the case of American-born detainee Yaser Esam Hamdi, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor said the court has “made clear that a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation’s citizens.” Congress did give the president authority to hold Hamdi, a four-justice plurality of the court said, but that does not cancel out the basic right to a day in court.

The court ruled similarly in the case of about 600 men born outside the United States and held indefinitely at a U.S. Navy prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. The men can use American courts to contest their captivity and treatment, the high court said.

The Supreme Court sidestepped a third major terrorism case, ruling that a lawsuit filed on behalf of detainee Jose Padilla improperly named Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld instead of the much lower-level military officer in charge of the Navy brig in South Carolina where Padilla has been held for more than two years. Padilla must refile a lawsuit challenging his detention in a lower court.

Steven R. Shapiro, legal director of the ACLU, called the rulings “a strong repudiation of the administration’s argument that its actions in the war on terrorism are beyond the rule of law and unreviewable by American courts.”

The administration had fought any suggestion that Hamdi or another U.S.-born terrorism suspect could go to court, saying that such a legal fight posed a threat to the president’s power to wage war as he sees fit. “We have no reason to doubt that courts, faced with these sensitive matters, will pay proper heed both to the matters of national security that might arise in an individual case and to the constitutional limitations safeguarding essential liberties that remain vibrant even in times of security concerns,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote for the court. O’Connor said that Hamdi “unquestionably has the right to access to counsel.” The court threw out a lower court ruling that supported the government’s position fully, and Hamdi’s case now returns to a lower court.

The careful opinion seemed deferential to the White House, but did not give the president everything he wanted. The ruling is the largest test so far of executive power in the post-September 11 assault on terrorism. O’Connor said the court has “made clear that a state of war is not a blank check for the president when it comes to the rights of the nation’s citizens.” She was joined by Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and justices Stephen Breyer and Anthony Kennedy in her view that Congress had authorized detentions such as Hamdi’s in what she called very limited circumstances, Congress voted shortly after the September 11 attacks to give the president significant authority to pursue terrorists, but Hamdi’s lawyers said that authority did not extend to the indefinite detention of an American citizen without charges or trial.

While I wish they had ruled on the Padilla case, the opinions appear to strike the correct balance. Clearly, judicial review is essential to due process–especially when American citizens are involved. The logic of the Padilla sidestep is odd; the jailer is merely a functionary carrying out policy.

The early reactions by the press are mixed, judging from the radically different headlines initially applied to the same AP story:

- NYT — Supreme Court Affirms Detainees’ Right to Use Courts

WSJ [$] — Court Gives Bush Partial Win In Enemy-Combatant Rulings (Hat tip: Barry Ritholtz via e-mail)

LA Times — Justices Say Bush Can Hold Citizens Without Trial

ABC News — Bush Can Hold Citizens Without Trial

USA Today — Court delivers mixed verdict on Bush terrorism detention policies

BBC — Terror suspects get court access

Seattle Post-Intelligencer — Enemy combatants may challenge captivity

Dozens more at GoogleNews

Reuters has its own account, which is essentially identical to the AP story — Court: Foreign Terror Suspects Can Use U.S. Courts

Financial Times uses the Reuters accounts with a more biased headline — Court rules in favour of U.S. terror detainee

Melbourne Herald Sun — Held ‘terrorists’ may sue

Update: WaPo has its own version as well — Detainees, Combatants Can Challenge Detentions

The remainder of the AP story:

Two other justices, David H. Souter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, would have gone further and declared Hamdi’s detention improper. Still, they joined O’Connor and the others to say that Hamdi, and by extension others who may be in his position, are entitled to their day in court.

Hamdi and Padilla are in military custody at a Navy brig in South Carolina. They have been interrogated repeatedly without lawyers present. The Bush administration contends that as “enemy combatants,” the men are not entitled to the usual rights of prisoners of war set out in the Geneva Conventions. Enemy combatants are also outside the constitutional protections for ordinary criminal suspects, the government has claimed. The administration argued that the president alone has authority to order their detention, and that courts have no business second-guessing that decision.

The case has additional resonance because of recent revelations that U.S. soldiers abused Iraqi prisoners and used harsh interrogation methods at a prison outside Baghdad. For some critics of the administration’s security measures, the pictures of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison illustrated what might go wrong if the military and White House have unchecked authority over prisoners.

At oral arguments in the Padilla case in April, an administration lawyer assured the court that Americans abide by international treaties against torture, and that the president or the military would not allow even mild torture as a means to get information.

The cases are: Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (03-6696) and Rumsfeld v. Padilla (03-1027)

I haven’t read the opinions, just the press summaries. If the latter are accurate, though, it reverses that sequence: The president and DoD handle the cases as they see fit and then the prisoners have a right to get judicial redress.

I am truly curious whether or not, as an American soldier held as a POW in another country, I would be given the right (to paraphrase) ‘to use their courts to contest my captivity and treatment.’

While it is popular to take the moral high road and espouse the belief that we should grant anyone we control many of the same rights as American citizens, the reality of terrorism needs to be addressed. We will not win a war againt a group beheading our prisoners on global broadcasts while granting redressment rights once we catch them.

While I am loathe to say it has to be done, rights of certain people must be trampled in order to stop this scourge. Americans at home simply don’t seem to have a grasp on how tenuous this situation really is.

When a terrorist attacks and kills Americans and their interests, the focus quickly becomes who is to blame for not watching them and what rights of those who perpetrated the act need to be protected. The bottom line is that when a terrorist takes up arms against the United States they are the enemy. You destroy the enemy. You don’t coddle and try to retrain him. And you certainly don’t look to your own as a scapegoat for the enemy’s actions.