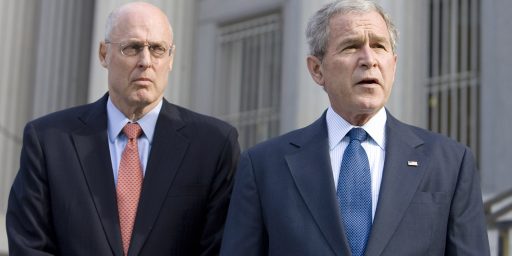

Luigi Zingales on Why Paulson is Wrong

Zingales starts of with an example and then asks a good question,

When a profitable company is hit by a very large liability, as was the case in 1985 when Texaco lost a $12 billion court case against Pennzoil, the solution is not to have the government buy its assets at inflated prices: the solution is Chapter 11. In Chapter 11, companies with a solid underlying business generally swap debt for equity: the old equity holders are wiped out and the old debt claims are transformed into equity claims in the new entity which continues operating with a new capital structure. Alternatively, the debtholders can agree to cut down the face value of debt, in exchange for some warrants. Even before Chapter 11, these procedures were the solutions adopted to deal with the large railroad bankruptcies at the turn of the twentieth century. So why is this wellestablished approach not used to solve the financial sectors current problems?

The short answer is we don’t have time for Chapter 11. But does this mean that the Paulson plan is the right one? No. The Paulson plan is for the government to buy or gaurantee the questionable assets that many of these financial institutions have.

If banks and financial institutions find it difficult to recapitalize (i.e., issue new equity) it is because the private sector is uncertain about the value of the assets they have in their portfolio and does not want to overpay. Would the government be better in valuing those assets? No.

Quite right. The current problem was caused, in part, by the opaque nature of these assets.

The Paulson RTC will buy toxic assets at inflated prices thereby creating a charitable institution that provides welfare to the rich—at the taxpayers’ expense.

I’ve gone through an actual industry crisis unlike most of my co-bloggers and probably many of the commenters. I was there before it started, I was there while the crisis was in full swing, and I was there when the crisis ended. The California electricity crisis. One thing to keep in mind is that the state of California did exactly the wrong thing: they ran out and bought a bunch of energy contracts at crisis level prices. Now we have extremely high energy rates in large part because we have to service these contracts. Brilliant, eh?

And of course as some might recall, the solution to the crisis was a regulatory one. The regulator in charge, FERC, finally stepped in and imposed a flexible price cap that prevented game playing. Of course, what most people don’t realize is that it was also a regulator issue that set the stage for the crisis. State regulators and legislators froze the retail rate while letting the wholesale rate flucutate. Unlike the current crisis, there wasn’t much that was opaque. As I noted the retail rate (the rate consumers had to pay) was set by regulatory fiat. The utilities were legally bound to buy all electricity needed by the consumers at the frozen price. Wholesale suppliers, the generators, were allowed to do pretty much as they pleased. What regulators and those in the industry failed to appreciate is that after decades of having vertically integrated and regulated monopolies the current system was set up with a least cost approach. As such there was just enough transmission capacity. There was just enough generation capacity. This created a situation where the people generating electricity (and this was no longer the utilities in the state) had quite a bit of market power and market power means higher prices

So, will Paulson’s plan work? I doubt it, but even worse is that it will create a situation where good risks are kept private along with the profits while the bad risks are made public along with the losses. That is the financial institutions will get to keep the good stuff and the tax payers will get the toxic stuff. I’d rather do nothing that implement this kind of a plan.

So what should the government do? Zingales suggests debt-foregiveness.

Since we do not have time for a Chapter 11 and we do not want to bail out all the creditors, the lesser evil is to do what judges do in contentious and overextended bankruptcy processes: to cram down a restructuring plan on creditors, where part of the debt is forgiven in exchange for some equity or some warrants. And there is a precedent for such a bold move. During the Great Depression, many debt contracts were indexed to gold. So when the dollar convertibility into gold was suspended, the value of that debt soared, threatening the survival of many institutions. The Roosevelt Administration declared the clause invalid, de facto forcing debt forgiveness. Furthermore, the Supreme Court maintained this decision. My colleague and current Fed Governor Randall Koszner studied this episode and showed that not only stock prices, but bond prices as well, soared after the Supreme Court upheld the decision. How is that possible? As corporate finance experts have been saying for the last thirty years, there are real costs from having too much debt and too little equity in the capital structure, and a reduction in the face value of debt can benefit not only the equityholders, but also the debtholders.

Now one could ask, “Well if this is such a good idea, why isn’t it being done?” Good question.

There a number of reasons. First off is the coordination problem. Imagine you have 10 people holding debt for a company. If some of that debt can be foregiven then the company would be more financially sound and could continue operations, otherwise the company faces serious risk of having to go out of business. Now if 3 people other than myself step forward and forgive their debt I’m strictly better off. This logic is true for everyone who holds the debt, so there is an incentive to not be the first mover. Another thing is if there is a bailout of the company I might get all of my money back or at least a significant chunk of it. This too reduces the incentive to forgive debt. And the Paulson plan has another thing going for it. It is the case of the many, us taxpayers, transferring money to the few. Taxpayers are poorly organized, have no lobbyists, and are ill-represented in Washington. I can’t call up Secretary Paulson, Chairman Bernanke, or any of the other major people involved. But I bet Citi-Groups lobbyists can get on the blower with these gentlemen in fairly short order.

Zingales concludes,

The decisions that will be made this weekend matter not just to the prospects of the U.S. economy in the year to come; they will shape the type of capitalism we will live in for the next fifty years. Do we want to live in a system where profits are private, but losses are socialized? Where taxpayer money is used to prop up failed firms? Or do we want to live in a system where people are held responsible for their decisions, where imprudent behavior is penalized and prudent behavior rewarded? For somebody like me who believes strongly in the free market system, the most serious risk of the current situation is that the interest of few financiers will undermine the fundamental workings of the capitalist system. The time has come to save capitalism from the capitalists.

The whole article is here.

No.

The short answer is that government wasn’t invlved in creation of those liabilities.

No Bithead, in this case we have days possibly weeks to decide on something. Chapter 11 can take years. Time is a luxury we do not have.

Dow Corning took nine years to complete Chapter 11.

There are reasons to believe large financial institutions might be more problematic. The assets and liabilities are in complex arrangements. Many of these assets and liabilities are held by other financial institutions that might be forced into bankruptcy as well.

And while providers of concrete goods and services have been able to continue operations during reorganization, its questionable whether financial institutions, whose stock and trade is “trust,” can do the same.

I think this notion that the government should be using bankruptcy-like powers in some piecemeal fashion is troubling. Zingales seems to be arguing that the greater good would be for the government to go around and reduce debts. Maybe, but in my view the government should only be able to do this if the government pays for the debt reduction.

Perhaps I don’t understand the “cram down”, but if the restructuring plan is forced on the creditors by the government, doesn’t this solve the “I’m not going to be the first debt-forgiver” problem?

Having now read the SCOTUS decision referenced, Perry v. U.S. (1935), I don’t think it has anything to do with what is being proposed.

In the 30s, the government devalued the currency and voided contract clauses that sought to bypass currency devaluation. Five members of the SCOTUS ruled that voiding such contract clauses was within the government’s power to regulate the value of money.

Zingales isn’t talking about revaluing the dollar or printing more dollars, he is talking about selective debt foregiveness in the financial sector. I don’t see the comparison at all. The government doesn’t have the power to go around and write off other people’s debts for the greater good, does it?

Hmm. I would have thought that this conflicted with the Contracts Clause, but evidently SCOTUS thought otherwise. There’s a discussion, initiated by Eric Posner, of the Contracts Clause and the Dodd plan over at the Volokh Conspiracy: The Dodd Plan: A Contract Clause Problem? that might be worth reading on this issue (especially the comments).

You’re arguing practical application and logistics, and in that framework, we don’t disagree. You’re quite right, it would take far too long to be effective.

I’m arguing OTOH, from more of a ethical principle stanpoint.

He appears to be saying that they do since that was the effect of the policy put in place by Roosevelt and upheld by the Supreme Court.

As for the discussion at the Volokh Conspiracy it might be relevant, but it is looking at home mortgages as debt for homeowners. For a financial institution such mortgages would be considered assets, unless I am mistaken.

He’s looking at it from an economist point of view. A lot of things have the effect of reducing a debt, including tax policy.

From a legal p.o.v., I don’t have a problem with the government printing money, or buying companies or their assets. It’s when the government starts retroactively changing the rules by picking debts to reduce, voiding employment agreements it no longer likes, butting in front of prior secured interests, etc.

We fix our mistakes, learn from our mistakes and go forward. We don’t go back and change the rules.

The Contracts Clause only apples to states, but there is another point that Prof. Posner is missing. When a company is insolvent, i.e. it does not have enough assets to pay its creditors, it’s speculative as to whether there are any property or contract rights to speak of.

Shorter version: I owe you $1 million, but I have no assets and minial income expectations. What property or contract rights do you have against me? I believe a court would say that you have none worth mentioning.

So….Does Mario think Paulsen is right? His opinion is important too… since he may wind-up as the head of the SEC!

Hey! Yoshi thinks the plan is Great!