The UK’s Problematic Electoral System

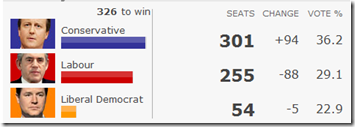

The preliminary results from the elections in the UK underscore the need for electoral reform in that country. Now, the UK uses the same system as the United States to elect the House of Commons, i.e., single-member districts with plurality winners. However, because of the presence of a number of third parties (as Chris Lawrence did a good job of describing yesterday), the results of the elections (and this is not a new phenomenon) are such that the overall preferences of the voters are not reflected in the actual results. Specifically, one can see from the graphic from the BBC that the Liberal Democrats have the support of 22.9% of the voters (less than 7% less than does Labour) and yet they are projected to have 201 less seats than Labour in the new parliament. This is a rather substantial amount of disproportionally. Indeed, the gap between the Conservatives and Labour in terms of the percentage of the vote is almost the same, and yet the difference in seats is rather dramatic.

And yes, I fully understand that the reason for the disparities is that Labour won more constituencies (i.e., districts) than did the Liberal Democrats. However, any electoral system that so poorly translates popular preferences into elected office is problematic from the point of view of basic democratic theory. For what it is worth, US elections actually does not suffer from the same problem, given that there is a fairly close fit between party vote shares and party seat shares which is due to the lack of seriously viable third parties. Indeed, disproportionality in the US is more comparable to many proportional representation systems than it is to other single-member district systems (source: unpublished manuscript). Our two party system is one of the most solidly two party in the world, in fact (almost uniquely so).

Meanwhile, the Conservatives in the UK are going to try and form a government (via the BBC: Election 2010: Cameron to try to form government). Labour may try as well.

If anything, the LibDems and their supporters have to be a bit depressed today, as the polling had them, at times, in second place, and all indications seemed to be pointing to a potentially historic day for them. Instead, they appear to have actually lost seats.

See also, Matthew Shugart: What if they held an election and everyone lost?

UPDATE (James Joyner): I’m blogging this at New Atlanticist: “Britain’s Hung Parliament: What Now?” and “Britain 2010 and America 2000.”

The idea of proportional representation across a whole country when seats are competed for locally district by district should be anathema.

Well, it is pretty much impossible to have PR across a whole country where seats are competed for in single member districts. As such, I am unclear on your point. I think you are basically saying that you just don’t like the idea of PR, yes?

A quick addition: I would note that what typically happens is PR is produced via multi-member districts that both capture local interests as well as better representing the actual preferences of the voters.

The UK didn’t have the tradition of partisan gerrymandering, restrictive ballot access rules and of course outright violence (ask the Populists in the South) that led to the present American two-party system though, did it?

As far as multi-member district PR being anathema, all I can say in the Republic of Ireland, with choicevoting in multi-member districts (3,4 or 5 seaters) the usual complaint is that legislators are too concerned with their district, rather than the opposite.

Isn’t comparing the US to a parliamentary system an apples/oranges thing?

We’re talking two different institutional frameworks, here.

The US has its own proportionality problems–namely the undemocratic allocation of Senate seats (which, in turn, gets translated to the Presidency via the Electoral College).

My sense is that party power in electoral systems are generally a reflection of and a response to institutional parameters.

@Triumph:

While there are clear campaign effects that influence the parliamentary v. presidential party systems in the UK v. the US, comparing House of Reprentative (or even both chambers of Congress) to House of Commons elections is about as apples-to-apples as you can get in a general sense: they are all SMD elections with plurality winners (also known as First Part the Post, or FPTP elections).

The Senate problems are about quality/nature of representation, rather than one of proportionality (which is simply a measure of the differential between vote-shares and seat-shares).

And, really, electoral systems are institutional factors. Although certainly other institutions in the system influence one another.

Still, the basic dynamics of the process to elect the House of Commons and the House of Representatives are quite similar.

The comparison of Congress and Parliament on the issue of correlation between voter preference and outcome seems an apples to apples comparison.

But watching several hours of BBC coverage last night, the British also want a stable government to be produced by the process. There was a smattering of embarrassment, confusion and amusement that the election occurred and a government may not be known for some time. Or as one pundit put it, the people have spoken, the democratic moment is over, now it’s time for closed door deals to decide who governs Britania.

And the deal that seems to be at the center of discussions is some form of proportionate representation preferred by the LibDems that would probably increase uncertainty and instability.

Two quick comments:

1) The LibDems are highly unlikely to get PR. Indeed, it seems rather unlikely that electoral reform will happen. The proposal that Labour was willing to pursue was the alternative vote (aka Instant Runoff) which would keep single member districts and ultimately require 50%+1 to win a seat (more discussion/explanation here).

2) The confusion at the moment is because it is simply unusual for the UK to have this kind of outcome. If the system produced more proportional results, coalition-building to form a government would be the norm, and would not cause instability, rather the parties and the public would adjust to the new normal. It happens around the world all the time.

Yes. I see no way to square PR with “all poiltics is local.” Any electorate that implements PR is further marginalizing a significant share of its population and brings to fruition our Founder’s concerns about a few large population areas (read states) dominating the smaller or weaker ones. In fact, it’s ever closer to a pure democracy, which is supposed to be bad, I think.

@Charles:

A lot could be said about this, but a few thoughts:

1) None of this is about “pure democracy” by which is meant direct democracy (i.e., the people directly governing themselves). This is all about representative democracy (what Madison called a republic in the Federalist papers). The issue is how well the public is represented.

2) The states are simply boundaries around citizens and the states themselves are constructs that have no interests apart from those citizens, as such any system that better reflects the interests of the citizenry is an improvement in democratic (read: representative) quality.

The issue of state representation, per se, is one that is a whole lot more about the politics of 1787 than they are about those of 2010, to be honest (although we are so ingrained with the notion that the original political agreement was so wise that we think that that wisdom persists to this day undiluted by time). There is simply no good reason why the voice/views/vote of a resident of Wyoming should be worth more than mine or yours (let alone of a Californian or Texan–and I was once one of both of those as well).

3) In fact, not all politics are local (with all due respect to Tip O’Neil’s brilliant book title).

4) Still, it is quite possible for a PR system to represent local interests. A comment about this notes one example. However, I can guarantee you that even a body elected nationally (i.e., one national electoral district) can still contain within it politicians oriented to local interests (this is certainly true, for example, in the Colombian Senate, which elects 100 members from 1 national electoral district as well as in the Israeli Knesset, which elects all its members in one national district as well–granted, Israel is geographically small, but Colombia isn’t).

Thank you Prof. Taylor for clarifying my confusion. Wouldn’t an instant runoff system run a significant risk for the LibDems to receive fewer seats? I would think such a system would eventually favor the largest parties. I’ve seen the LibDems described as a none-of-the-above party, chief recipient of tactical votes, and a party lacking a consistent national platform.

@PD:

It is difficult to fully predict the effect of IRV on the UK. I would have to look at constituency-level historical data to make a good guess, but it is my initial gut reaction that IRV would help Labour at the expense of the LibDems. As such, one would think they are likely to be uninterested in that system.

They may, however, be desperate enough about their situation at the moment to roll the dice.

Thank you for your engaging, civil responses. A few months of those and even I might become a reasonable poster.

Charles: thanks.

What would be the voting system you think is best for the USA? There are issues with our system, though for our current makeup, it works OK. But is there a better voting method we should consider?

Funny you should ask–I just posted something that touches (at the end) on that issue.