Are our Problems Based in Leadership or Institutions?

Where should we look to understand the failings of the government?

Conor Friedersdorf asks an interesting question (and one that I have seen in various iterations of late): Is America Suffering from Rogue Leaders or Broken Institutions?

Conor Friedersdorf asks an interesting question (and one that I have seen in various iterations of late): Is America Suffering from Rogue Leaders or Broken Institutions?

For someone like me, whose academic area of study is institutions, this is a rich and intriguing question which spawns a number of possible responses (which means picking a place to start is difficult). Let me lay out here a basic description of the problem as I see it (and as I think it is being discussed elsewhere) and suggest some initial responses to the the question.

First, there is some vagueness to this basic discussion. In a general sense it seems to be asked as a general proposition founded in the fact that the economy currently is running rather poorly, which creates an overall feeling of discontent with government (and frustration from various political factions who think that the solution to the problem is more of whatever it is that they like). Further, we find that we ask questions like “is the government broken?” when the economy is involved in a long-term downturn.* There is also, however, a specific set of examples of perceived failings, a partial list of which follows:

- Bush administration policies on enhanced interrogations/torture, warrantless wiretaps and the like that did not result in significant hearings or investigation.

- The Obama administration and Libya (and its seeming contravention of the War Powers Act).

- The Obama administration’s killing of Anwar al-Awlaki and at least one other US citizen (Samir Khan) via drone attacks in Yemen.

- The entire debt ceiling standoff.

- The pending potential failure of the deficit-cutting joint committee.

I would note that is all of the issues linked to presidential action, one can have an opinion about whether Bush or Obama violated the law, but at the end of the day that is all that it is: an opinion. Absent actual legal proceedings of some kind we are left with ambiguity (and hence a legitimate critique of institutions for not adequately triggering such legal actions or leadership for failing to initiate available institutional tools). The fiscal matters are yet a whole other set of problems (which I will leave aside for the moment).

Regarding the foreign policy/war on terror issues above, I do agree that Congress has appeared unwilling to assert itself, something I have noted (and criticized) in the past. Such unwillingness to more seriously confront the executive branch is a failure of leadership, to be sure. However, I would argue that, on balance, this lack of actions is founded very heavily in a lack of adequate institutional incentives and ability to adequately engage the topics at hand.

Some specifics:

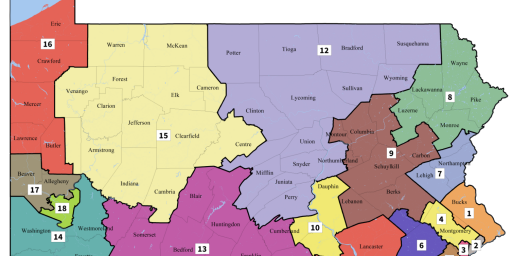

The Feedback Loop. As Madison noted in Federalist 51, “dependence on the people is…the primary control on the government.”** What this ultimately means is that candidates have to fear elections. They have to believe that what they do in office will affect their jobs when they go before the people. However, most of the members of Congress do not have this fear. We have a substantial number of uncompetitive House districts in the country, many of which have been specifically engineered by state legislatures to be that way based on partisan motives. This is an institutional flaw that damages democratic feedback. And for those who do not believe me, we have a natural experiment coming up in November of 2012: we will go into House elections with that chamber having remarkably low approval rates, and yet a massive number of Representatives will be re-elected. If that is not evidence of a problem with democratic feedback, I don’t know what evidence would look like.Of course, there is a broader problem, I would argue, with our electoral system, as the combination of the primary system and single member districts with plurality winners means a party system that is inadequately representative of the political interests in the country and that cements the current rigid bipolarity that dominates our politics (something a lot of gripe about, but really appear unwilling to address). Of course, the issue of serious electoral reform is whole other discussion, but just looking at the system as it exists and judging it by its own design, the massive number of utterly safe districts (especially those gerrymandered to be safe) clearly demonstrates a problem. Lack of competition is bad for democracy.**

Limited Options for Congress. The truth of the matter is that the Constitution gives Congress limited options in dealing with the executive. The only real power in question is impeachment, which is really designed for serious malfeasance (“Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors”) not policy disagreements. Even if one thinks that the President violated the law in terms of Libya or al-Awlaki, the impeachment process is a pretty extreme (and blunt) method of dealing with it (and, given the super-majority requirement for removal in the Senate, a basically unrealistic one save in the aforementioned extreme circumstances). Congress, Ron Paul not withstanding, is rather unlikely to use impeachment in these types of situations. Another option, the congressional hearing, ends up being much more show than anything else. Having said that, I personally would prefer to see more hearings, as attention is needed on many of these issues, even if the hearings themselves are flawed and are largely toothless.

As such, the main institutional tool under the Constitution to deal with a president who isn’t doing what the Congress wants him to do is the calendar: i.e., to wait out his fixed term of four years and hope that the election will change the occupant of the White House. We have no “no confidence” vote nor the ability to call early elections.

Impasse, in general, whether it be in terms of formulating complex policies, or whether it comes in the guise of how Congress should address problems it perceives with presidential action is built in to our institutional structure (i.e., bicameralism itself as exacerbated by the internal rules of the Senate). Let me note the obvious: the Congress is currently split between the two parties. As such, serious action against the president is highly unlikely (to put it mildly).

In sum: there are some serious institutional factors that very much are contributing to our policy problems at the moment.

These are just some thoughts on this complex subject. I expect to have a few more posts on this at time allows.

—-

*We can see this question being raised in the later 1970s/early 1980s, for example, including some scholarly attention at the time to the question of whether the presidency was inadequate given the size and complexity of the of the United States.

**Of course, he goes on to discuss “auxiliary precautions” which, ultimately, means institutional design. This is a topic for another post.

***Or, if one prefers, bad for a representative republic.

I think broadly American society misunderstood the transition from Cold War American dominance to “the new order,” whatever that was to be. That the Neocons saw it as a search for an enemy was strange in the first place, that they felt so strongly that they had to push and subvert institutions to make it happen was beyond strange. It is bizarre in retrospect that Iraq became their focus. Of all the problems in all the world …

I think we still have a tin ear and a disconnect (see below).

A new Lost Decade is leading to revolution

That might be overstated in scale, a bit, I hope, but I don’t think its wrong is spirit.

America’s problems are primarily the fault of a particularly dumb and greedy crop of CEOs running out major corporations.

I think the very institution of Government by the People is the problem.

The founders were elites, to a man. But the form of government they devised inevitably leads to government by the lowest common denominator. So in answer to the headline: It is a problem of Leadership that has been created by the Institution.

To be absolutely clear I am not advocating against Government by the People. I am advocating against non-elites.

I think that Hey Norm is onto something but I’m not sure that I agree with the details. Yes, Jacksonian democracy presents some problems. However, Jacksonian democracy still managed to produce quite a number of leaders for 150 years.

I think it’s not the fundamental construction of the institutions but the way in which they have evolved recently. By far the greater number of those in the Congress are apparatchiks and career office-holders. That’s not conducive to cultivating leaders.

Unfortunately, increasingly governors are cut much from the same cloth. That’s particularly true in states that have weak governor systems.

Well, Dave and Norm, remember who our elites are these days. It’s wealth more than class, which ties of course to this week’s protests against “the 1%.”

I don’t see this as 1:1 with Occupy Wall Street, but there is a little overlap. The wrong directions taken in the last 10-20 years produced both the Tea Party and this current event.

I’m not really sure what you mean in practice – do you mean getting rid of elections? An oligarchy of public minded elites running things for the betterment of the unwashed masses? Philosopher-kings (and queens) governing the masses who are too stupid to govern themselves?

That might sound snarky, but it isn’t meant to be – I’m not sure in practice how you have both Government by the People and Government by Elites.

@ George…

Yeah…me neither.

How do you get elites to run for office…and disuade idiots?

Big question…I got nothing.

I just know it’s a problem.

The Constitutional framework contains many inherent ambiguities, but can be very clear in certain areas regarding criminal procedures or legislative process. On the war-related matters, Friedersdorf seems unaware of centuries of ambiguity about the role, if any, of the Congress. On the other hand, the notion that we should find ways to punish Presidents is going to run smack into very clear criminal safeguards.

(I hope some of you aren’t saying the answer is to trust the 1% [more])

What’s your definition of “non-elites”?

As the Bard once observed, the fault lies not within the stars but in ourselves.

Abuse of power exists to the exact degree that power exists. That’s why the founders had the notion of limited governmental power… a notion the left rejects.

Not me – I think it was Bertrand Russell who pointed that the opinions and advice of the elite – academic and financial – is as varied and no more accurate than that of the masses, it just tends to be phrased better.

Some of this is because society is extremely complex, I doubt anyone does (or can) really understand it well enough to make useful predictions on how it will react (unlike say a point particle in Newtonian physics), some of it because any elite (academic, financial, football fans) will automatically try to arrange things to benefit what they believe strongly in. I’m an engineer, if in power I’d inevitably overemphasise the importance of science (and then within that, overemphasise the engineering I personally do). I don’t think there’s any way around that, even with well-meaning elites. And the following generation of elites probably won’t be that well-meaning, which is what happened in America I think.

A serial regurgitator of warmed over talking points such as yourself should probably avoid quoting people who actually knew/know how to think and write. The contrast between literate thought and low grade drivel is simply mind-numbing.

Friedersdorf has some valid points, but his piece was triggered by the Awlaki killing and he focused on presidential abuses of power, stuff like the first four items on Taylor’s list. Taylor, however, broadened the discussion to include our economic situation, the paralysis of congress, and our general discontent. If we’re talking about broader failings, Taylor ignores the elephants in the room: Republicans and money.

If you want to understand where we’re at, read Hacker and Pierson, “Winner Take All Politics”. Our government is becoming more and more controlled by corporate money. Look at Citizens United and K Street. Look at this weeks’ article in the New Yorker about how one guy, Art Pope, basically bought the government of North Carolina. And this money leans heavily Republican. Republicans have dominated politics in this country for the last thirty years. They’ve built a huge and effective propaganda apparatus, from AEI to FOX News and the handlers of the Tea Party, that has driven conventional wisdom way to the right.

If you want to look at failings of leadership or institutions, look at the Supreme Court. Unless we make it a requirement that appointees to the court recognize the difference between speech and money, democracy in the United States won’t last another thirty years.

I am amused to see an article which purports to ask the question about whether our problems are the faults of the leadership or the institutions, and then spends so little time with the large number of recent institutional changes (especially in Congress) which have made governing more difficult, from the rise in filibusters to secret holds to the de facto requirement of obtaining the support of the majority of the majority to bring legislation to a vote to the politicalization of the confirmation processes to playing hostage games with routine business of government (such as the debt ceiling). With so many new road blocks thrown in the way of passing legislation, it is hardly a surprise that so little is getting done.

@Moosebreath: Actually, I am planning on addressing the filibuster in a separate post. I did note it here (albeit perhaps too obliquely):

As noted in this post, there is an awful lot to cover on this topic, which is why I said “These are just some thoughts on this complex subject.”

@Steve — if plurality, first past the post single member districts with severe gerrymandering explains the dysfunction in the House, then what explains the polarization in the Senate as the districts don’t change (the electorate’s do change, see Pennsylvania 2006 and 2010 to produce Casey, a fairly generic mostly liberal Democrat, and Toomey, a hard right reactionary Republican)

I think there is more going on, and the biggest thing is that the parties are ideologically sorted and mostly coherent in the technical sense of the term. That produces much stronger party incentives and basic system design of the US government produces dozens of chokepoints that previous norms had discouraged pressure from being continually applied against them.

@Dave Anderson: Well, as I tried to note in the post, I am not trying to explain everything–it is, after a blog post, and this topic is worthy of a book…

I do think that the non-competitive nature of the House districts (Senate districts can’t be changed, so I focus on the House here) are a major, fundamental problem that we largely ignore, which is why it is one of the things I thought worth bringing up first.

And yes: the numerous choke points, as you put it, is the most fundamental issue (and it is one of institutional design).

Steven –

This is it right here! When the approval numbers of the POTUS creep towards 40%, there is a great gnashing of teeth. Yet, Congressional approval has hovered under 25% for as long as I can remember and they all keep getting elected. 2010 was widely seen as the ultimate throw the bums out election, yet the reelection rate in the House was still approximately 85%.

Our legislature has no incentive to be responsive to the people and every reason to be responsive to the bagmen. How can we expect this to work?

Choke points? How do they equate to Checks and Balances, and the prevention of evolution of a one-party, one band of elites, total and complete majority rule, or a one-philosophy runaway government? Much of what has transpired I believe has been the attempts at blocking of unilateral legislative directions by one party against the other, opposition party (whether loyal or not, in or out!).

Some of these conflicts really represent several undesirable aspects and inherent difficulties: What is best for the nation versus what is best for the people, versus what is best for the States, versus what is best for the party, versus what is best for the inner group, versus what is best for my constituents, versus what is best for me to get reelected, versus what I decide that is best.

It would seem that we are seeing emphasis on best for the party/inner group/reelection/I decide/constituents well before what is best for the nation/people—and the States only get unfunded solutions. We the people are the losers.

Steven,

I think you misunderstood my point. I would say that there has been a shift in the institutional norms in the last generation, which has prevented Congress from passing anything. I think that if the institutional norms were the same today as those Reagan or LBJ faced, far more would be accomplished.

Do we really want philosopher-kings, singly or in small clusters, to rule the nation? Elites or pseudo-elites, wealthy, middling or poor, or declared czars, do not have a comforting track record for sterling governance in history. Intellectual elites, especially public intellectuals, can be charged with some of the most disastrous eras in history when they somehow managed to grab the reins of power. The image of a Noam Chomsky or a Ward Churchhill at the controls sends me looking for my parachute. Broad spectrum common sense is a rare commodity in elite circles, as are money smarts and military smarts, as well as real and honest appreciation for the true worth of the ordinary citizen, who is immediately relegated to the status of pawn in the games of state. I believe that to a man they have read Machiavelli’s “The Prince” and then developed their own abridged, ego-serving version.

The Founders assumed that each part of the government would jealously guard its powers. They did not foresee how we would evolve into a system where party comes first. Our institution has become much too dependent upon the good will of those who are elected to it.

Steve

@Hey Norm:

Do y’all know where the word ‘idiot’ comes from? It’s from the Greek for ordinary citizen (idiotai). The Athenians distrusted elections, thinking that they led to rule by undesirables. They did have a few elections. For instance, they elected their generals. But all the governmental entities in Athens were populated by lottery. Any Athenian citizen could be selected by lot to serve on any governmental entity. Ordinary citizens, idiots, ran the country. And did so very well for over 200 years, until Athens was undone by its own hubris in the Peloponnesian War. (The Athenian democracy was finally overthrown for good by Phillip; but the Athenians never ceased trying to restore their democracy.)

The final word in Athenian democracy lay with the Assembly. A Council of 500 citizens, in general, proposed decrees that were voted on by the Assembly. The Athenians made a distinction between laws —nomoi–and decrees. Roughly, think the distinction between our constitution and statues enacted under it. The nomoi were handed down by lawgivers in the past, e.g., Solon.

Here’s the part that’s really interesting. In addition to the Counci of 500, any Athenian citizen could, theoretically, propose decrees in the Assembly. In practice, insofar as this was done, it was done by elite citizens, elite by wealth, birth, and — importantly — elite by education in rhetoric. This was an oral culture, remember. One very important reason why the elites took on this task was if one proposed a decree that was deemed illegal according to the nomoi, one was liable to fine and/or imprisonment. The vast bulk of the Athenian citizenry could not afford to pay any fines, and certainly weren’t keen on going to the pokey, so it fell to those willing and able to take the risk — the elites. But imagine that: somebody proposes an illegal (unconstitutional) decree and is severely punished for doing so. That’s something to conjure with.

I think one can argue the U.S. is a failed state in terms of how effectively it operates within the confines of its own construction.

Its institutions, born not of divine inspiration as many assume, but of heavy compromise have not maintained sufficient “memory” from the Founding to keep the country more or less “in line” with the restrictions placed within the Constitution. Was this the fault of bad leadership? To a certain extent, yes. There are few nations which have agonized for so long over original intent, and 220 years later we battle over the subject as much as ever, perhaps moreso. But the Founders themselves began violating their own principles almost immediately after the document was ratified; Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson made the Louisiana purchase. Madison invaded Canada in a war of conquest. Hamilton usurped Presidential powers during the Quasi-War. Only Washington and Franklin could be said to have remained “true” in some sense, and interestingly enough, among the Founders their names may be the least invoked for guidance.

I would suggest these acts of naked ambition, opportunism and ego ultimately had more of an impact on America’s future course than the Constitution, and gutted institutional resistance to abuses of power before it could become fully entrenched in the country’s bureaucratic and judicial “DNA” for lack of a better term. Future presidents (some more than others) vigorously followed in the footsteps of this dynamic, aggressively expanding American power at every opportunity. Or perhaps we could say that our institutions haven’t failed, but that the imperial presidency and the permanent pursuit of dominance are, in fact, our institutions. From that perspective America ten years into the War on Terror hasn’t diverged from the Founders’ example, it simply became more itself. The logical conclusion of an imperfect birth.

@mannning:

By chokepoints, I mean anonymous holds, I mean instituting a majority means 60% to rename a Post-Office etc.

It might be rather difficult to measure the distance we have crept from the fresh new Constitution and its original intent and compromises to the current position our laws and practices are in today. The first push/pull was undoubtedly centralized versus distributed power, and centralization has won out in practice. It continues to do so, with the office of the president leading the way. From a purist point of view, we have expanded the scope of our laws well beyond the Constitution and civil laws envisioned in the beginning, most often due to pressures to meet a stream of new needs discovered that the Constitution neither covered nor thought to cover, and with the willing collusion of all three branches of the federal government to cater to these needs, ostensibly of the people, and, of course, for the good of the nation.

Books have been written about the role of the Supreme Court in deviating, in interpreting, and in legislating from the bench to achieve some functional goal not possible to achieve in any other manner. Seizing the decision powers of an autocratic leader by the Presidents has also been a continuing drumbeat pushing us ever further away from a strict adherence to the Constitution. Whole governmental departments, with their missions, functions, budgets, and staffing have been invented through legislation to meet these new needs and functions, and this process is even accelerating today. Earmarks fit into this creep also! I have often pointed out that currently there are over 1,177 separate organizational entities in the government with budget lines, staffing and all the trappings of bureaucracy. In fact they tend to stumble over each other in their zeal to approve or disapprove actions brought before them. Try to obtain approval for a new nuclear power plant and you will be dealing with an entrenched bureaucracy of 23 or so different organizations at last report.

The maze grows yearly, and even Reagan could only kill or rework some hundred of these entities, and it seems that he was about the last to try. We have grown many monster bureaucracies since his time, and Obama has created hundreds more yet to fully surface. To say that this gaggle has become unmanageable and unaffordable is to bring the wrath of entrenched congressmen, lobbyists, and advocacy groups down on your head, as well as the party or parties that stood behind the legislation in the first place.

Why don’t we commission an independent group to take on the decade-long task of streamlining this governmental gaggle, much as BRAC did for military bases? It would be a many-year task, and it would spawn quite a few Constitutional amendments as it went along, I suppose, but the commission would end up paying for itself ten, twenty or more times over I’d guess, to the benefit of our bottom line. ( Avoiding a Constitutional convention would be a prime objective here, since the scope of such a convention cannot be controlled, and we just might end up worse that we began!)

@manning

Yes, well, I’m sure the Founders were able to envision the history of the last 100 years.

@samwide:

Why, I always thought the Founders walked on water! Surely they could perform such a mundane trick as seeing hundreds of years into the future (as if they needed to!). What the hell are you on?