Bachmann, the Constitution, and Slavery

Bachmann's views on the Founders and slavery are more significant than simply a question of how to classify John Quincy Adams.

After the debate yesterday here at OTB and elsewhere in the Blogosphere about Michelle Bachmann, John Quincy Adams, the Founders, and slavery, I decided to go beyond the interview with George Stephanopoulos and look at the speech by Bachmann that sparked the question in the first place.

After the debate yesterday here at OTB and elsewhere in the Blogosphere about Michelle Bachmann, John Quincy Adams, the Founders, and slavery, I decided to go beyond the interview with George Stephanopoulos and look at the speech by Bachmann that sparked the question in the first place.

The segment of significance is as follows:

“we also know that the very founders that wrote those documents worked tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States”

The JQA ref comes next:

“And,” she continued, “I think it is high time that we recognize the contribution of our forbearers who worked tirelessly — men like John Quincy Adams, who would not rest until slavery was extinguished in the country.”

The transcription is via TPM.

If one prefers to hear the words directly, here’s the video (the relevant section is at roughly 10:23):

Now, starting with JQA: if we separate him from “the very founders that wrote those documents” and place him in the category of “our forbearers” then she is on safe ground. And yes, JQA, especially later in his career, did become a vocal opponent to slavery. The degree to which “he would not rest until slavery was extinguished” is debatable, insofar as it makes it sound as if it became the singular focus of his life. Being an opponent, even a public one, is different than being an activist dedicated solely to single issue. Still, within the context of the speech, one can give her the JQA reference. Of course, in the interview with Stephanopoulos she actually made the JQA issue worse rather than better by placing him the “founder” category.

The real problem with her history, however, is the first quote above. The authors of our founding documents in fact did not work “tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States.” Yes, some opposed it and did make efforts to end it (Benjamin Franklin in the best example), others understood the contradictions between said documents and slavery, but were unable to make the hard personal choices that would have been required to align their lives with their principles (e.g., Jefferson and Madison). Even Washington, who did the right thing in death (i.e., freeing his slaves), was unable to do so in life. Other Framers and Founders hoped that slavery would fade in a few decades (but hope is not working tirelessly), while yet others fully supported the institution.

Indeed, the quote makes it sound as if great efforts and whole lives were dedicated by these men to the cause of abolition. This was simply not the case.

Yes, the Declaration of Independence as written scolded King George III for promoting slavery. It was one of a long list of grievances. Indeed, that section of the Declaration is something of a “kitchen sink” list of everything bad that the colonists could blame on the King. However, the irony of that section is that a) Jefferson owned slaves, and b) King George was not actively promoting slavery. Indeed, at the time of the Declaration the movement towards abolition in Great Britain was starting in the courts (and slavery would be abolished there in 1833 sans a civil war). Beyond any of that, the fact that there was no serious movement post independence to free the slaves puts the anti-slavery portion of the Declaration in perspective (i.e., it was am invocation of the issue for rhetorical purposes, not because action was planned or desired on the topic).

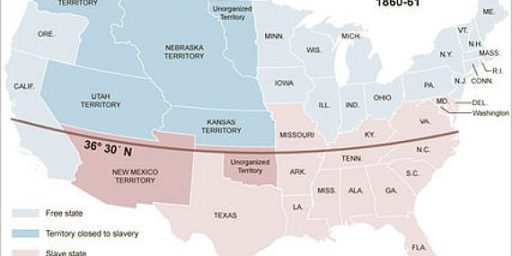

The Constitution has three key sections that can be construed as, at a minimum, tolerating slavery:

1) Article I, Section 2: “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.”

This is the infamous 3/5th compromise which acknowledged, however obliquely, the massive slave population in southern states and also ignominiously assigns them the value of 60% of a free resident.

2) Article I, Section 9: “The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.”

This is the Framers punting for twenty years. Essentially the slave trade would be left off the table for two decades. And note: this provision is focused on the slave trade, not slavery. So all it did was provide for the possibility of ending the importation of slaves after 1808. This was a clear political compromise, but make no mistake: this hardly qualifies as tirelessly working to end slavery. Yes, some thought slavery would fade given two decades, other didn’t. One thing is for sure: this is constitutional endorsement, however vague, of continuation of the slave trade for a period of time that many of the Framers knew would likely be after their deaths.

3) Article IV, Section 2: “No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.”

This, of course, references fugitive slaves.

Look, I fully understand the political reality on the ground in 1787. I understand the need, as distasteful a fact as it is, for political compromise on the slavery question. However, that was the reality: some of the Founders of the US, and specifically some of the Framers of the US Constitution, were pro-slavery. Indeed, as has been noted, two key Framers, Washington and Madison, themselves were slave owners. These are facts that have to be understood and dealt with.

Instead, Bachmann’s statement that “we also know that the very founders that wrote those documents worked tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States” is simply not true. This matters. And it matters for at least three key reasons:

1) It influences our understanding of the Constitution: too many people, and Bachmann and her supporters in general appear to fall in this camp, like to treat the Constitution as though Madison came down from the mountain with the document inscribed on stone tablets by the finger of God. In this vision, the Constitution is perfection (or nearly so) and it can be quoted as though it is holy writ. However, this is not the case. The Constitution, remarkable though it is for a variety of reasons, is not a perfect document. Further, it s a document that has to be understood as being shaped by politics and compromise.

2) The influences our understanding of the Founders/Framers: this is corollary to the point above. These individuals were a remarkable collection of individuals. Some were clearly geniuses. However, they were not prophets, nor demi-gods, and they certainly weren’t perfect. As such, as much as what they did and what they had to say are interesting, inspiring, and sometimes instructive, they are still just men.

3) It downplays the national sin of slavery: by making it sound as if there was a widespread, elite-driven effort from the very beginning to get rid of slavery is an alteration of the true narrative of the United States. Not only does it absolve, to some substantial degree, the Founders/Framers of sins committed, but it also creates the basis for a narrative in which things really weren’t so bad for blacks, because, after all, there were tireless efforts to free them from the beginning.

Indeed, if the Founders did work tirelessly to free the slave, then doesn’t that absolve us, as a nation, to some degree of said sin? After all, if the Founders fought against slavery, then those who were fighting for slavery were some Other People to whom we do not bear responsibility or allegiance. Don’t’ blame the Founders! No, they hated slavery, blame those Other People. That way we don’t feel so guilty and there no need to even consider the long-term effects of slavery on national development.

Further, this is part of a broader narrative that she weaves in the speech (check out around the 9:00 mark) where she paints the US as as place of perfect equality and integration. And, of course, if that is true, then we really don’t need much of asocial welfare system because if we all started out totally equal, then whatever lot you find yourself in at the moment must be your own fault.

I am not, by the way saying that if one has a more accurate understanding of the past that it necessarily leads to a specific vision for contemporary policy. I am saying, however, that I think Bachmann’s policy views, and indeed by extension some segments of the GOP and the Tea Party are illuminated by their specific interpretations of out past, our forbearers, and our key documents.

Lincoln disagrees and cited quite a few substantive things the Founders did against slavery. It wasn’t all a bunch of rhetoric like you suggest.

http://www.weeklystandard.com/blogs/george-stephanopoulos-historically-illiterate_575904.html

@VV:

That some Founders did some things is not the point.

Any serious discussion of this has to start with the three provisions of the Constitution that I noted.

Vast:

Lincoln was committing politics.

Steve,

You’re trying way too hard to explain this. Occam’s Razor would suggest that Bachmann – like pretty much every single politician since Silent Cal – is simply incapable of Just Shutting Up. If someone gives her an opportunity to talk, she’ll talk. Even if she has nothing to say, even if she doesn’t have the slightest idea what she’s talking about, she’ll talk, and she won’t stop until the cameras are turned off.

That’s not a crime – it’s not even abnormal (in politics). The only reason anyone’s even writing about it is because of her complete inability to backtrack. She has no reverse gear. When she says something, it’s correct, because she said it. You’ve just done a remarkable amount of research & writing in a short time, with full resources available. Do you _really_ think Bachmann had all that information in her head when she made these rambling stump speeches? Do you _really_ think Palin had some deeper insight into Paul Revere’s ride when she stepped on her tongue not too long ago?

No. They each made a minor misstatement. But rather than cop to it, or even move on and forget it happened, they insist that reality itself is wrong. And then well-meaning people like you come along and bend over backwards to avoid calling out what amounts to a dangerous narcissistic complex. Don’t coddle this psychological defect, Steven. It turns out bad for all of us.

@Michael:

A rather important point.

“No. They each made a minor misstatement.”

I am not sure about this. Remember, she went to Regent law school, an explicitly Christian law school (IIRC). I think she comes from a culture that writes and reads its own history books. I dont really know, but she may honestly believe what she has said and does not believe that she made a mistake. Her supporters will also have read the same sources and side with her, viewing this as an attack by people, like Dr. Taylor, who don’t know what they are talking about.

Steve

Actually, it IS the point. The questions of “what The Founders did” cannot be reduced to ONLY three provisions, none of which (pace Dred Scott) actually sanctified slavery or made it a right. They all recognized realities on the ground (a point you say you understand) and ruled on questions that come up in that context.

As for Lincoln “committing politics” (as if you two aren’t now), how does that rebut the historical actions he cites? Did they or did they not occur? And were they or were they not acts of the Founding Generation (i.e., pre-Jacksonianism)?

Here’s why this matters (to me anyway) — the question of whether the Constitution was an anti-slavery or pro-slavery was throughly debated in the 1840s and 1850s *within the abolitionist movement* with Lincoln and Frederick Douglass on the side that it was (and William Garrison Lloyd on the other). Lincoln and Douglass quite well knew of those provisions (Luncoln notes that Congress banning the slave trade as soon as it could as a measure of the Founding Generations’ sentiment). It really is a debatable question, but that’s not how Stephanopoulos and Politifact acted. Their wilding of Bachmann is pure born-yesterday temporal chauvinism (with a healthy dollop of partisanship tossed in).

Well, Bachmann is talking about a fictionalized version of history. Hardly a “minor misstatement”. She is either ignorant or a liar…

“I am not sure about this. Remember, she went to Regent law school”

Neither Bachmann went to Regent Law School.

Which makes the rest of your note read … rather hilariously.

As usual, it’s history as morality tale. Which is an offence not just to the facts but to the reality that the founding fathers were much more interesting than that. Some were indeed moral and intellectual titans, people who stand in the very first rank of historical glory. Some were opportunistic hucksters and cynics whose revolutionary zeal was oiled by the fact that wicked King George was standing in the way of them making shedloads of cash. The same, of course, applies to the other side, not least when it came to the issue of slavery and freed slaves. Cornwallis was a cynic who was quite happy to use blacks as a tool to be taken up or discarded at his convenience. Sir Henry Clinton and Sir Guy Carleton, on the other hand, were substantially truer friends to many slaves seeking liberation than many revolutionaries were.

One also has to wonder, if the Founders were so firm and united in their zeal to root out slavery, why so much effort was put into trying to force the British to return the freed slaves who had rallied to British colours into bondage.

“I am not sure about this. Remember, she went to Regent law school”

Neither Bachmann nor Palin went to Regent Law School.

Which makes the rest of your note read … rather hilariously.

Anjin-san,

I’m assuming (and it’s pure conjecture on my part) that she was confusing John Quincy Adams with his father John A., who actually was a “founding father”. If so, then yes, I’d call it a minor mistake for a stump speech. If, OTOH she actually believes what she’s been saying, then yes – that’s a bigger issue…

OK, attack the Virginians all you want for condemning slavery when their laws never seemed to get passed, but leave Lincoln out of it. He firmly believed that the founders wanted to end slavery and it was inconsistent with their intent for it to expand. It was intervening events, such as the cotton gin, disreputable politicians like Andrew Jackson, and the emergence of a pro-slave morality.

To expand on that last point, if one had asked Washington, Jefferson or Madison about slavery, each would say it was an evil abomination that must be ended. By the antebellum period, such a belief could have no place in the Democratic Party. Slavery had become a moral good. The Declaration of Independence was described as a self-evident lie.

Steven,

Jefferson wrote that provision, but it was removed by Congress. Over John Adams’ strong objection to the point that the Declaration almost never happened, yes. But it was removed.

I can’t agree with you more, though I have to add Frederick Douglass started as a Garrisonite, who believed the county was founded on slavery and then became persuaded and moved to speak to the contrary position later. You can read both arguments from him, and it was an important argument that presaged the Civil War.

Kind of agree with this. Everyone makes mistakes, says things off the cuff which are wrong. But most folks will admit that saying “57 states”, or “Hello Bolivia” were mispeaks, instead of doubling down.

She went to Oral Roberts, which closed the year she graduated. Oral Roberts is very much a Christian university, which makes the rest of his note perfectly relevant. In fact, Oral Roberts donated almost its entirely law library collection to Regent when it closed. Surely some of those books were of the Christian historical revisionist school steve alludes to. Bachmann herself helped move the library.

PD:

Ask every single politician in Washington and they’ll tell you they want to end deficit spending.

How many are “working tirelessly” toward that end?

Belief is cheap, action counts. The most relevant action taken by the Founders was to enshrine slavery in the Constitution and grant enhanced voting power to slave states. I don’t doubt the compromise was necessary, but talking about it as a relentless effort to end slavery would be laughable.

Anyone who speaks in public as much as politicians do is going to misspeak once in a while, get some facts wrong, etc. Not everyone doubles down though, insisting their misstatements and errors are actually factual.

If Republicans spent less time defending idiotic statements from their leaders and more time finding less idiotic leaders, our country would be a much better place.

And seriously Vast Conspirator, pry the () keys from your computer and try to compose sentences of less than fifty words.

That is all.

micheal, Jefferson’s Virginia constitution provided for the emancipation of slaves. He didn’t get the votes. He proposed that slavery be excluded from the West and this bill lost by one vote. You can’t say he’s all belief, and no action.

To use your analogy, if I say taxes should be raised, but don’t volunteer money from my own pocket to the government, am I a hypocrite?

One thing that usually gets overlooked in these discussions is New York, which had one of the most extensive and established slave systems in the colonies. Founding fathers John Jay, Aaron Burr and Alexander Hamilton worked tirelessly to end slavery in New York.

There’s a much bigger picture here.

Bachmann believes this country was founded in perfection – that’s the very definition of an originalist. There is no room for subsequent interpretation or the influence of time and a changing world. And if that is what you believe then there cannot have been slavery. The fact that there was slavery, and it was widely accepted and practiced by the founders, is too much for Bachmann to process. Reality requires her to think, and to ask questions, and to hold wildly contradictory ideas in her head at the same time. So instead she makes shit up. It’s the only way to rationalize her beliefs.

So the bigger picture is – is this the mental process you want from the person with their finger on the nuke button? As a whacky Congress Person from the mid-west that never actually passes any laws – OK – she’s pretty amusing. President of the United States – no thanks.

NO WARNINGS FOR LIBERAL HIJACKERS? geesh…

I think the more apt analogy would be if you loudly proclaimed your distate of deficits then refused all talk of tax increases and offered no real solutions on the spending side, you’d be a Republican, er, hypocrite.

A group of men go into a room. Some are opposed to slavery — but own slaves themselves and profit by the sweat of their brows. When everyone comes out of the room those men still own slaves, still pocket the profit, still enjoy the lifestyle, and they’ve signed a document that ensures legal status for slavery and offers enhanced, concentrated voting rights to slave owners.

I’m just not seeing where that’s tireless work to end slavery.

Norm,

Spot on. And it fits like a glove with her avowed religious conservatism too. The Word is The Word, and none may question it. As you say, a useful start for a charismatic talking head, but unspeakably dangerous when given any actual power.

First, Steven, brilliant post. It seems to me the summation of it is simply you need to write “some” founders did X. Period. That’s it.

To say the founders were all Christians or abolitionists or slave owners or federalists is a fundamental mistake. Further to constitute the founders as fighting against a “conspiracy” to maintain slavery that was outside the founders is, as you note a danger and a necessary move to make them “Exceptional” in the way that populists need.

Which gets to @Vast’s point:

True that it was not made an explicit right, but you also cannot deny that these provisions sanctioned the continued practice of slavery and made two key moves that help further solidify a difference in the eyes of the law between Slaves and Whites:

1. Article IV, Section 2 — Which as Steven points out implicitly establishes slaves (a human) as property of another human, with no claim to rights of citizens.

2. 3/5 of a man — which again establishes that these people are not equivalent people.

I realize the political work that was necessary to come to these compromises — but they stand as a fundamental reminder that the founders were NOT ALL working against slavery.

I’m not a historian, so please correct me if I’m wrong, but all this appears to break down to the failure by many to recognize that the Founding Father’s were not a monolithic group.

The only extent, to my knowledge, you could attribute uniform agreement include: a vague notion of an American Revolution against the British Empire, the signing and support for the Declaration of Independence, and the framing of the US Constitution. Of course, much of this was the result of argument and compromise itself. Beyond this, it’s pretty unreasonable to suggest there was any monolithic consensus on what their words and actions meant.

And to expand on this a little, I think the argument can be made, and is in many ways undeniable, that the Founding Father’s did put the wheels of “freedom” in motion. Though this would not be the same as saying they worked collectively towards all the fruits of freedom that came down the road. And the fact is we are still arguing and interpreting the meaning of the word “freedom” today.

@Vast:

There can be no “Pace Dred Scott” for a really important reason. Reviewing Chief Justice Taney’s decision, one discoveres exactly what is dangerous about Michelle Bachmann’s use of history. In the excerpts I reproduce below, you will see he makes exactly the same move — converting the founders into a single cohesive whole — and then proclaiming them “unitied.” Except Taney argues they were united in their:

a. Support of Slavery as an Institution

b. Their belief that People of Color were fundamentally inferior to White.

In fact, one section is particularly telling (and haunting):

The logic of this passage stands in direct opposition to Bachmann and in support of the points many of us are making. If the founders tirelessly fought slavery, than the inclusion of the slave provisions in the Constitution represented the height of hypocrisy and a reason to “rebuke” them.

When faced with the inherent contraditions of words and action, neither Bachmann or Taney can take the difficult path. Each resolves it in the extreme — for Bachmann, we ignore the actions and words of some founders to create a history where they all worked to destroy the institution; for Taney, the only possible answer is that all of the founders must have supported slavery.

Either way, historical fact is twisted in order to justify a political claim (nothing new, but at least in Taney’s case, the assurance that the founders supported slavery — rather than fought it — becomes the basis of denying Scott and all other slaves their freedom).

The entire descision can be found here: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h2933t.html

And below are key excerpts highlighted by me…

mattb, that’s the entire point, Taney was wrong. People who knew he was wrong were outraged (Lincoln returned to policis for one thing) because they disputed his fundamental misconception of history.

Note that the direct implication of Taney’s ruling was that the Northwest Ordiance was unconstitutional. When the founders passed abolition laws, they can’t get credit for it because some twisted, corrupt justice argues it’s inconsistent with their intent.

@PD — I think we’re in (at least partial) agreement. The point of those two posts is that the totalizing move (a la Bachmann and Taney) is often used to provide a lot of cover for taking all sorts of action. Sometimes it can be good, but not always.

Saying the founders worked tirelessly to remove slavery is an “easy path” and gives warm fuzzies by painting a past full of moral heros, helping us to see us and them in the best light.

But what happens when — on some other issue — Bachmann (or anyone else) uses that unity to justify a bad decision (i.e. the founders were all Christian (as was England before) and that demonstrates that the Constitution and Declaration were inherently Christian Documents — so clearly religious freedom was understood by all to really mean “Christian” only — and really was only placed there to prevent the establishment of a Church of the US — Judism, Islam, and other imperfect and/or degenerate religions are clearly not intended to be protected).

Taney stands as a reminder that people should understand that *some* of the founding fathers (and later generations of Americans) fought for what we, today, think is right. And understanding that also means not forgetting that they stood in opposition to other founders (and later leaders of the country) who fought to support — or passively allowed to continue — institutions we deeply regret.

That doesn’t mean we damn Washington or Jefferson, but we don’t give them a free pass in order to make ourselves feel better about ourselves.

Well, as my final post on this topic, I’ll just summarize:

Any descent history book of the early years of the Republic will acknowledge the unprecedented rise of the call for abolishing slavery. Prior to 1770, there is essentially nothing. Zip. Nada. When the colonists became concerned about their rights, they began examining in earnest the implications of their new philosophical tent pole, and most of the founding fathers north of the Carolinas can be attributed to working hard to pass abolition laws, restricting slavery and the slave trade. Indeed, the Northwest Ordinance banning slavery in the Northwest territories passed with only one dissenting vote. Banning slavery from the West entirely lost by only one vote. (OH, the what ifs!!!)

The real historical question is how or why did that effort peter out? There is a lot of finger pointing on this question. I have my opinions and have read a lot of others. But one opinion that emerges a lot is the certainty that slavery was on it’s way out. The last measure of strength was not wasted on a dying institution. Was it self-deception? Was it a trick of fate? I think there are several reasons, but I don’t believe one of them is that the founding fathers made their peace with slavery.

One take-away is history does not always progress the way we think. Pro-slavery sentiement became stronger, not weaker, as many founders hoped or expected. Similarly, racist sentiments grew stronger, not weaker after the Civil War. The Whig view of history has to take into consideration setbacks and turns.