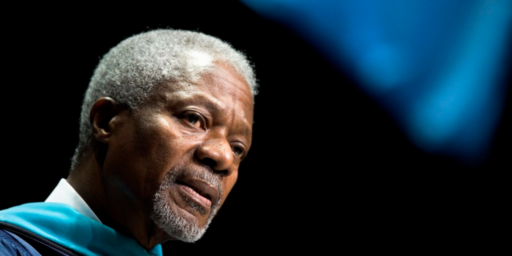

Boutros Boutros-Ghali Dead at 93

The godfather of the Responsibility to Protect doctrine has passed.

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the first UN Secretary General from the African continent, has died.

BBC:

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the former secretary general of the UN, has died aged 93.

His death was confirmed by Rafael Dario Ramirez Carreno, the president of the UN Security Council.

As an Egyptian, Mr Boutros-Ghali was the first Arab to hold the UN’s top position.

He took office in 1992 at a time of increasing influence for the world body following its decisive role in the Gulf War, serving one five-year term.

The 15-member Security Council observed a minute’s silence.

ABC:

Boutros Boutros-Ghali, a veteran Egyptian diplomat who helped negotiate his country’s landmark peace deal with Israel but then clashed with the United States when he served a single term as U.N. secretary-general, has died. He was 93.

Boutros-Ghali, the scion of a prominent Egyptian Christian political family, was the first U.N. chief from the African continent. He stepped into the post in 1992 at a time of dramatic world changes, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the end of the Cold War and the beginning of a unipolar era dominated by the United States.

But after four years of frictions with the Clinton administration, the United States blocked his renewal in the post in 1996, making him the only U.N. secretary-general to serve a single term. He was replaced by Ghanaian Kofi Annan.

The current president of the U.N. Security Council, Venezuelan Ambassador Rafael Ramirez, announced Boutros-Ghali’s death at the start of a session Tuesday on Yemen’s humanitarian crisis. The 15 council members stood in a silent tribute.

Boutros-Ghhali died Tuesday at a Cairo hospital, Egypt’s state news agency said. He had been admitted to the hospital after suffering a broken pelvis, the Al-Ahram newspaper reported on Thursday.

Boutros-Ghali’s five years in the United Nations remain controversial. Some see him as seeking to establish the U.N.’s independence from the world superpower, the United States. Others blame him for misjudgments in the failures to prevent genocides in Africa and the Balkans and mismanagement of reform in the world body.

In his farewell speech to the U.N., Boutros-Ghali said he had thought when he took the post that the time was right for the United Nations to play an effective role in a world no longer divided into warring Cold War camps.

“But the middle years of this half decade were deeply troubled,” he said. “Disillusion set in.”

In a 2005 interview with The Associated Press, Boutros-Ghali called the 1994 massacre in Rwanda — in which half a million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed in 100 days — “my worst failure at the United Nations.”

But he blamed the United States, Britain, France and Belgium for paralyzing action by setting impossible conditions for intervention. Then-U.S. President Bill Clinton and other world leaders were opposed to taking strong action to beef up U.N. peacekeepers in the tiny Central African nation or intervening to stop the massacres.

“The concept of peacekeeping was turned on its head and worsened by the serious gap between mandates and resources,” he told AP.

Boutros-Ghali also came under fire for the July 1995 Serb slaughter of 8,000 Muslims in the U.N.-declared “safe zone” of Srebrenica in eastern Bosnia just before the end of the war.

In 1999, families of the victims listed Boutros-Ghali as one of the international officials they wanted to sue for responsibility in the deaths.

His legacy was also stained in investigations into corruption in the U.N. oil-for-food program for Iraq, which he played a large role in creating. Three suspects in the probe were linked to Boutros-Ghali either by family relationship or friendship.

His cousin, Fakhry Abdelnour, is the head of an oil company called AMEP, which was accused of getting oil concessions through the executive director of the oil-for-food program, Benon Sevan.

Boutros-Ghali frequently took vocal stances that angered the Clinton administration — such as his strong criticism of Israel after the 1996 shelling of U.N. camp in Lebanon that killed some 100 refugees.

In writings after leaving the U.N., he accused Washington of using the world body for its own political purposes and said U.S. officials often tried to directly control his actions.

He wrote in his 1999 book “Unvanquished” that he “mistakenly assumed that the great powers, especially the United States, also trained their representatives in diplomacy and accepted the value of it. But the Roman Empire had no need for diplomacy. Neither does the United States.”

Ghali was rightly controversial and less than stellar as a manager of the UN. His legacy, however, was enormous.

I’m in the midst of teaching my course on US interventions into civil conflicts and Ghali’s name comes up constantly. His leadership was critical in beginning a transformation in how we think of sovereignty. From the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 through the early 1990s, the bedrock principle of international relations was that the leadership of a state had virtually absolute authority to do whatever it wishes internal to that state. The power of the sovereign was, in theory at least, absolute so long as it did not have cross-border effects that impacted the sovereignty over other states. Starting with the demise of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, however, we started to see a view that sub-state actors—groups of people and even individual people—had rights that deserved protection from the international community. Ghali was a principal architect of that view. While the Responsibility to Protect doctrine wouldn’t emerge in full until well after Ghani’s term, he was in many ways its father.

![Military Coup Underway In Egypt [Update: Morsi Deposed]](https://otb.cachefly.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/egypt-flag3-512x256.gif)

This just makes me think of Seinfeld, in the episode where he saw a topless woman on the beach and exclaimed “Boutros Boutros Ghali”

R2P is dead as a doornail at this point. Deader than Boutros-Ghali, may he rest in peace.

@J-Dub:

Ask and ye shall receive:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRTAUVqcYBY

@Dave Schuler:

Isn’t R2P at the heart of the Western intervention in the Syrian civil war, though?

Yes, I realize that’s hardly a recommendation for the success of the idea but it still does seem to be a policy that is prompting the nations of the world to act.

@Doug Mataconis:

That may have been how it started but is that still the reason? I don’t think so. I think that now it’s more to be able to prove we’re doing something about DAESH.

@Dave Schuler: @Doug Mataconis: R2P is quite new, having been enunciated only in 2001 and ratified as customary law in 2005. It was alive an well as recently as the Libya intervention in 2011 and the core of the concept—that leaders of a state have a responsibility to protect their citizens from harm—remains very much intact. What is problematic—and always was—is getting anyone to do anything about it.

In the particular case of Syria, Russia is using its veto power as a Permanent Member of the UN Security Council to block any R2P response. There is precedent for workaround via NATO or another regional coalition but the political will isn’t there. But that doesn’t mean R2P won’t be invoked for a future, less internationally messy, conflict.