California Allows Police To Search Mobile Phones Without A Warrant

California's Governor has vetoed a bill that would have reversed a very misguided decision by that state's Supreme Court.

If you’re arrested in California and you have an iPhone, Blackberry, or Android smartphone on you, chances are the police are going to be looking through it to see what you’ve got on there:

California Gov. Jerry Brown has vetoed legislation requiring police to obtain a warrant before searching through the mobile phones of suspects at the time of arrest.

The veto means that police can search through suspects’ mobile phones anytime they are arrested in California.

(….)

Brown said that the courts were better to resolve the issue of privacy and constitutional search-and-seizure protections in a statement issued after the veto.

“I am returning Senate Bill 914 without my signature. This measure would overturn a California Supreme Court decision that held that police officers can lawfully search the cell phones of people who they arrest. The courts are better suited to resolve the complex and case-specific issues relating to constitutional search-and-seizures protections,” wrote Brown.

The case which Brown refers to in his statement is Diaz v. California [PDF], a case in which the California Supreme Court had ruled that police could search a suspects cell phone incident to a lawful arrest. The California legislature responded by passing a bill that would have limited police authority to search mobile phone incident to arrest to circumstances where the police had requested and obtained a search warrant from a magistrate. Governor Brown, who has not governed as the sterotypical liberal that many remember him being during his tenure in the 1970s, apparently believed that this was an issue that the Courts should decide. However, as Orin Kerr points out, this gets the issue precisely backwards:

It is very difficult for courts to decide Fourth Amendment cases involving developing technologies like cell phones. Changing technology is a moving target, and courts move slowly: They are at a major institutional disadvantage in striking the balance properly when technology is in flux for the reasons I developed in this article. In contrast, legislatures have a major institutional advantage over courts in this setting. They can better assess facts, more easily amend the law to reflect the latest technology, are not stuck following precedents, can adopt more creative regulatory solutions, and can act without a case or controversy. For these reasons, legislatures are much better equipped than courts to strike the balance between security and privacy when technology is in flux.

This strikes me as largely correct, not the least because Courts can only deal with these issues as they are presented to them. It may take years for the “right” case regarding the application of the Fourth Amendment to technology like mobile phones to make it through the Court system. When it does, the courts will base their decision on the facts of the case before them, which may not precisely match the facts of every police-citizen encounter involving these devices. Therefore, it’s unlikely that the Court would create a general rule that is always applicable to cell phones. The number of distinctions that can be made are numerous. Should it matter, for example, if the phone is password protected? What if the owner of the phone uses it to access work and personal email? What if the owner of the phone is an attorney and the material on their includes privileged client communications? Under the California statute, all of these situations would have been dealt with in one simple rule requiring a warrant. The Courts could take years to resolve issues like this.

Typically, when the police arrest someone they are permitted to conduct a search to ensure that the suspect is not carrying weapons, and doesn’t have access to anything that could be a danger to the officer or anyone else. Police are also permitted to conduct inventory searches when an automobile is taken in for impoundment incident to a lawful arrest. If incriminating evidence is uncovered during one of these searches, it is typically considered admissible despite the fact there was no search warrant. The Diaz decision, though, expands that authority to allow police to search through a cell phone as much as they wish without a warrant. There really isn’t any conceivable “safety” exception that can be applied here, nor does there seem to any real inventory excuse here. Nonetheless, thanks to the extent to which Federal and State courts have degraded the 4th Amendment in recent decades in connection with the War On (Some) Drugs and the War On Terror, it’s not at all surprising. In fact, just last week, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to even accept the appeal in Diaz, meaning that the decision stands in California and stands as precedent for other judges to be guided by if they choose. That’s not a good thing.

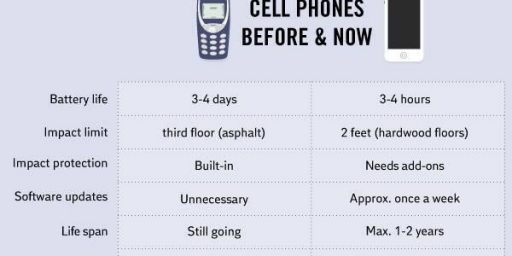

This isn’t an insignificant issue obviously. Smartphones are becoming more and more pervasive in society, and even “dumb” cell phones typically have information stored in text messages, voice mails, and call records. All of which are now available for police to search to their heart’s content once they’ve arrested someone. David Kravetz at Wired points out that there were 332,000 people arrested for felonies in California in 2007, one-third of whom, or more than 100,000, were eventually never charged. That doesn’t take into account people taken into custody on a misdemeanor. Now, it’s entirely possible that they’ll be brought into custody on one charge and end up being charged with something else, all because the police were able to search their phones without a warrant.

So, if you’re in California and you’ve got a smartphone, be careful what you keep on it I guess.

Absolutely. It is the courts’ job to interpret the laws, and the Legislature’s job to make the laws. If the People, through the Legislature, decide the latest interpretation isn’t sufficient, then the laws can be changed, and the Courts have to deal with it (assuming the new law is constitutional). That’s the way it’s supposed to work. Brown’s action is completely inappropriate – it effectively gives Legislative authority to the Judiciary. WTF?

From a practical standpoint, the next question becomes what limits law enforcement’s ability to compel you to unlock your phone or give them the password.

If you can unlock my phone, search it. Waterboard me for the password, if it means that much to you.

This goes so beyond “Papers, Please” it strains absurdity.

@Boyd:

That’s exactly what I was wondering too. And to Doug’s point:

As more and more devices have access to the cloud, the question becomes what limits the power of the police to conduct warrentless searches.

@mattb: And further to that point, the possibility of unwarranted (as in, without a warrant) searches of my phone by law enforcement is the sole reason why it’s locked with a password (well, technically it’s a “pass gesture”).

Not surprisingly, the Defendant in the Diaz case was a drug suspect, picked up in connection with a buy-and-bust purchase of Ecstacy.

Put security software on your phones, folks. I have automatic backup of all data, a lock on the phone which will wipe all the data if too many failed attempts are made, and I can wipe it out remotely and lock the phone down if I want. I don’t have anything incriminating on my phone, and the security measures were put in place in case I lose it or it is stolen, but it works just as well for the cops. I can’t even be said to be destroying evidence, I don’t believe, because it is being copied elsewhere (somewhere the police would need a warrant to access, of course).

@Boyd:

@mantis:

Doesn’t do any good, the cell manufacturers include an interface for a device sold to law enforcement that allows them to transfer the contents of a phone to a computer for forensic analysis, completely bypassing the security. They don’t need your password to get in.

Yup, you’d have to hotkey it to wipe – which is easy to implement, but kind of a pain if you accidentally wipe it. Probably not worth the effort.

Doesn’t do any good, the cell manufacturers include an interface for a device sold to law enforcement that allows them to transfer the contents of a phone to a computer for forensic analysis, completely bypassing the security. They don’t need your password to get in.

I can wipe it by inputting a password before it is confiscated, or I can do so remotely if I have access to a computer. Honestly, if they are bothering to go through what you describe, I would probably be in custody for something serious. This is highly unlikely, and my main motivation is keeping Officer Traffic Stop from poring through my phone just because he can.

Governor Brown is turning CA into a police state. First, the insane law forcing schools to teach the “gay” agenda (forcing thousands of parents to take their children out of school and move to another state), the law requiring HPV without parents permission (state control of children), now cell phones can be seized. Add to that the scandalously high gas tax in California and the ban on Happy Meals in San Francisco. Very quickly approaching Soviet Union status. Get out before he seals the state lines.

They told me if I voted for Meg Whitman that I would set back personal liberties. Turns out they were right.

@george:

@mantis:

If you wipe the phone, now they have you on obstruction or destroying evidence.

Wow! Whatever happened to Gov. Moonbeam? I thought the court ruling got it wrong, but Brown has made matters even worse by vetoing the legislation. Need to see what’s on a cell phone. Get a warrant. It’s not all that difficult to show probable cause.

@James in LA:

James,

Given that password protecting your computer wont stop them from searching it, I doubt whatever password you have on your phone will slow them down much.

@mattb:

Then they will read your e-mail.

@mantis:

You can’t wipe it while in jail I’m afraid.

@mantis:

Yeah, try fumbling around for your cell phone while being arrested.

@Fiona:

He is a statist. There does that help. And keep on voting it is doing oh so much good.

Suckers….