Drug War 101: Drug Control Budget

Ok, since there was some confusion generated by some of my previous posts on the drug war, let’s start to simply look at some basic information so that we can perhaps, over time, establish some foundational issues from which discussion can be held.

My general position, so that it is clear, is that we are no getting what we are paying for in the drug war but that the public, in general, thinks that we are. This is evident by the fact that really any serious public discussion of changing the policy by a politician is typically considered political suicide, as any discussion of altering the basic approach of the policy is considered being soft on drugs and crime and surrender (after, all it’s called a war for crying out loud!). Regardless, however, of my position, there are still some basic facts that need to be understood.

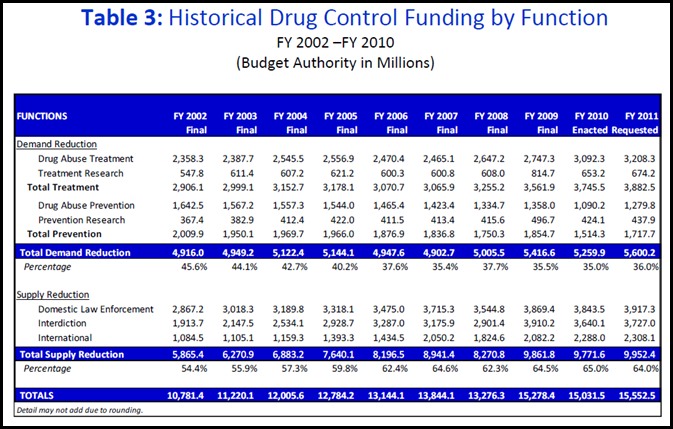

Let’s start with money. The below is taken from FY 2011 Budget Summary (Table 3: Historical Drug Control Funding by Function [PDF]) as published by the Office of National Drug Control Policy, which is part of the Executive Office of the President and is the clearinghouse for US drug policy. The head of the ONDCP is colloquially known as the “Drug Czar.”

A couple of basics that should be noted. First, as I described in a previous post, there are two components to anti-drug policy, the demand side (drug consumers) and the supply side (production, manufacture, transport, and sales). Where one focused the policy is key. It is possible, for example, the focus heavily on the demand side by looking at education and treatment. Some countries pursue policies that are more focused on the demand side. Supply side policies are heavily focused on interdiction and law enforcement.

From this table we can see a few things. First, the annual anti-drug budget is an 11-figure number: the FY2011 request is $15,552,500,000. That is a lot of money, especially in the context of growing budget deficits and debt. It is therefore not unreasonable to ask if the money is being spent efficaciously. That is, by the way, a starting point in a discussion, not an end point.

Second, it is worth noting that our policies are increasingly aimed at the supply side (specifically on the international and interdiction lines). Is that increase achieving its goals? If one looks at Mexico, for example, one would have one’s doubts. Indeed, an NPR story this morning noted that in Mexico “Fighting among the cartels — and between government forces and the cartels — has cost nearly 24,000 Mexican lives since Calderon took office in late 2006.” That is during a period of increasing spending by the US government. We are currently set on spending $1.3 billion specifically on Mexico. I would note, by the way, that some will likely respond that things have gotten better in Colombia of late. This is true, but “better” is a relative term (and itself a very lengthy discussion). Beyond that, in terms of the drug war, all that we have managed to do is shift the locus of the conflict from Colombian to Mexico. It is worth considering if, in fact, that represents a good return on investment. Put another way: one could argue that we have invested tens of billions of dollars to simply move the fight closer to our borders (and the drugs still flow).

I will reiterate the following, as some readers appear not to have understood the following in my previous posts: the key metrics that end up being used by the US government (as well as the UN and others focused on the supply side of the equation) are hectares under cultivation, hectares eradicated, amount of drugs seized, the price of the drugs in question, and arrests. These are not my metrics chosen to make the policy look bad, they are the metrics used by the designers and defenders of the policy.

As such, when I pointed out that from 1990-2007 that the wholesale price of cocaine has declined, the reason for doing so is to demonstrate that despite the considerable expenditure of taxpayer dollars that the policy is not achieving one of its goals. Price is indicative of supply. Yes, as some have noted, it is not the only factor. However, the basic parameters of the black market in drugs (which inflates the price by itself) were well in place by 1990 and there was reason to assume that the pressure placed on producers and traffickers over a sustained period of time would constrict supply. While there has been some, often temporary, effects on supply, the policy has failed to produce the desired results. Pay attention next time that there is even a small spike in price, and the likelihood is that the ONDCP or some other organization will cite it as evidence of drug war success.

The hectares under cultivation issue is also key for drug warriors. The ONDCP and the UN love to point out how many hectares of coca have been destroyed. But the point of my post on the subject is that while there was a marked decrease in cultivation starting in 2002, the trend then flattens out. This suggests that the policies were able to attack the low-hanging fruit, so to speak, initially but that the cultivators were able to adapt. If the policy was really working, each year there ought to be less and less cultivation. Instead, there isn’t. More money and activity have not resulted in less coca being grown from 2002 onward. How is that success? How is that an effective expenditure? (And no, those aren’t rhetorical questions). Again, do look at the charts.

Link up steady production with little effect on price (indeed, a downward trend on price) and we have a situation in which is it fair to call into question the supply side approach by its own metrics.

One thing that would be useful to add to the discussion is an example “what if”. My understanding is that the Dutch went with a total “if it feels good do it” approach to drugs. Tracking their expenditures from before and after would be worthwhile.

For example, a significant piece of the “war costs” you present is for drug abuse treatment. Would legalization just move the costs from interdiction to treatment cleaning up after wide spread availability. Likewise, while drug costs should be significantly lower when legal vs illegal, are the legal drug costs rising or falling in constant dollars. In other words, is there something other than the legal status driving costs. Finally, the unintended consequences. What has the Dutch experience been. Are they losing large swaths of there people dropping out and just doing drugs or is it like alcohol here that while there is abuse, there are functioning, productive people from all strata who participate.

Looking at the results of a real world counter example may show that concerns are real or that unintended consequences are worse. With out going into the merits of the issue, the 40 million+ abortions in the US since 1973 have undoubtedly had an impact on our social security financing issues. That wasn’t the intent or even part of the discussion in the debate, but it is an example of a real world unintended consequence.

Supply has undoubtedly the most significant impact on price, but there are other factors as well. The risk associated with importing and selling contraband also influences price siginificantly, although as you have noted the money spent to increase the risk probably isn’t delivering the bang for the buck that would be expected in any kind of cost benefit analysis to justify its continued expenditure.

I submit that The prohibition of recreational drugs is not the proper role of a free

country’s government.

Every justification for the prohibition of recreational drugs can also be made for the prohibition of hot dogs, cheeseburgers and a long list of other unhealthy foods.

Heart disease kills a lot more people than illegal drugs. Do we want our police arresting and jailing people for eating unhealthy foods? I

hope not. Do we want our police arresting each other for eating doughnuts? Maybe.

There is a great deal of killing, stealing and people prostituting themselves so they can get their doughnut fix. “Sarcasm offâ€

If recreational drugs only harm that person or mild indirect financial cost to others, I wouldn’t have a problem with them. However that is not true. From what I have heard on the Dutch system, legalizing it is not very wise thing to do.

Does the domestic law enforcement figure include the cost of incarcerating minor drug offenders (possession, possession w/ intent)? If not that seems a significant factor to add. Consider also that most of our prisons are overcrowded with some having to set up three high cots in common areas.

What have you heard? When i lived there a few years ago there problems with drugs seemed dwarfed by ours both in terms of % of population using and in terms of violence theft and other crime related to distribution or usage.

Their system certainly has flaws; the most glaring of which is that is is legal to possess soft drugs, it legal for ‘coffee shops’ to distribute some and for ‘smart shops’ to distribute the others, but there is no legal way for the coffee shops or smart shops to acquire the drugs that they sell which leads them to acquire some of their drugs from rather unsavory characters. All in all though it seems a much more sane policy than what we have at present in the US.

No it doesn’t.

Depending on where you go for the stats between 20% and 50% of the jail and prison population is there for a drug offense. Taking the lower estimate that amounts to over 400,000 people in prison directly because of a drug offense costing upwards of $20,000 per year which yields a conservative estimate of $8 billion per year. Definitely a cost that should be considered.

You are correct.

Second, it is worth noting that our policies are increasingly aimed at the supply side (specifically on the international and interdiction lines).

These matters don’t usually arise in a vacuum. There could be political pressures, there could be diminishing returns on other alternatives, there could be situation specific factors which mandate a response on the supply side.

The data you provide documents an interesting finding which casts some doubt on how the public interprets your characterization of funding being disproportionately directed at supply side initiatives.

We see that in F2009 $3,561.9 was spent on Drug Treatment and $1,854.7 on Drug Prevention while only $3,869.4 was spent on Domestic Law Enforcement. The American public mainly intersects with Drug Policy in the domestic sphere, so funding dedicated to battling drug trafficking outside our borders has little bearing on how people form their perceptions on the efficacy of Drug War policies. They see police activity, drug dealing, drug arrests, drug violence, consequences of drug use, incarceration data, treatment options, prevention initiatives, and, on balance, we’re spending more on the demand side than we are on the supply side.

The fastest rising spending has been on the Drug War as fought on the battlefields of interdiction and in the international sphere. Domestic law enforcement spending (2003-2009) has risen 35% compared to 104% for interdiction and 111% for international efforts.

This data suggests a few possible interpretations:

1.) There is lower marginal utility in the prevention and treatment programs;

2.) Prevention and treatment programs are not politically saleable;

3.) There is higher marginal utility in interdiction and international operations than in domestic enforcement; and

4.) Spending on interdiction and international operations is more politically saleable than increased spending on demand side reduction or on domestic enforcement in that while the gains might have lower marginal utility they don’t produce any, or as much, political consequence because they have less intersection with the domestic political sphere.

Is that increase achieving its goals? If one looks at Mexico, for example, one would have one’s doubts.

If we posit the following: Drug War on Colombia resulted in some success by moving the Drug War to Mexico.

If that hypothesis has merit, then we need to examine the alternative scenario, which is that the Drug War in Colombia was scaled down and drug influence in that country increased because the US was not exerting external pressure to address the drug infrastructure in Colombia.

So, between these two scenarios, if the US better off with having the “drug industry” completely control the smaller government of Colombia and co-opt their military and other civil institutions in aid of drug industry goals or is the US better off by having the drug industry operating in a country like Mexico which has a population more that twice the size of Colombia’s and an economy that is 5x larger? Which country is better able to mount an internal defense against drug industry activities?

Yes, what we’re seeing is a balloon squeezing effect, but that doesn’t mean that the severity of the problem and the consequences that arise from a shifting of malignancy presents don’t change.

Beyond that, in terms of the drug war, all that we have managed to do is shift the locus of the conflict from Colombian to Mexico. It is worth considering if, in fact, that represents a good return on investment.

The shifting of locus, is on balance, appearing to be a positive outcome, in that the resources of the State now overpower the resources of the drug industry moreso than they did when the battle was between Colombia and the drug industry. As for your second question, it is far too premature to consider return on investment when we lack so much relevant data.

However, the basic parameters of the black market in drugs (which inflates the price by itself) were well in place by 1990 and there was reason to assume that the pressure placed on producers and traffickers over a sustained period of time would constrict supply. While there has been some, often temporary, effects on supply, the policy has failed to produce the desired results.

I’ve repeatedly pointed out to you that supply, when comparing the US market to the markets in other Western nations, is indeed restricted, as reflected by the US having one of the highest street prices for cocaine. This indicates to me that supply-oriented policies are working to a large extent. If you find this argument invalid then you need to actually address it and make your case for why you think it invalid and explain why the US price is so much higher than the price in Denmark or Switzerland.

Secondly, it would help if you examined what the results for the drug trade would be if all nations imposed interdiction and international eradication efforts similar to those of the US. The balloon effect works on both the production and consumption sides of the economic equation. If the US market poses importation obstacles, then suppliers will prefer to send product to jurisdictions with laxer border control and laxer domestic enforcement schemes, thus supplying the drug cartels with profit so as to cross-subsidize more elaborate schemes to bypass US interdiction efforts.

This concept might be easier to understand if we think of a military front manned by a coalition of armies each responsible for a segment of the front. When the enemy challenges the US held front they encounter quite a bit of resistance so they shift their movements to the fronts controlled by US allies and find that they can breach those segments far easier and loot from behind the lines. Then they use the proceedings of their looting to fund more intensive efforts to break through the US held line. How would the enemy fare if all the fronts were held with the same intensity as the US-held front?

Until we have some understanding of this alternative we can’t responsibly gauge the effectiveness of stand-alone US interdiction efforts because the Drug War/Drug Industry is not simply a two-player game.

This suggests that the policies were able to attack the low-hanging fruit, so to speak, initially but that the cultivators were able to adapt.

I agree. The drug industry has adapted. That doesn’t mean that the effort which forced the adaption was misguided, it only means that the US commanders of the Drug War are still fighting the last war and haven’t yet counter-adapted their tactics in response to drug industry tactics.

that while there was a marked decrease in cultivation starting in 2002, the trend then flattens out. This suggests that the policies were able to attack the low-hanging fruit, so to speak, initially but that the cultivators were able to adapt. If the policy was really working, each year there ought to be less and less cultivation. Instead, there isn’t. More money and activity have not resulted in less coca being grown from 2002 onward. How is that success? How is that an effective expenditure?

It’s a success by keeping the area under cultivation constant since 2002. The data you provide in this post suggest that yield has increased and that this is the factor that is primarily responsible for “more cocoa being grown from 2002 onwards.”

If the US initiative wasn’t focusing on lowering yield, then it’s a bit of a stretch to condemn US efforts for not preventing an increase in yield. It appears to me that the drug industry response to US efforts was to find a way to counter lower amounts of fields under cultivation by boosting the yield of cocaine product from each field.

Response and counter-response are variables that have time-lags built into them. A few of your blogging colleagues here are men with military experience, so perhaps they could add some unique insight from military history on this specific dynamic.

Tango,

Even if one accepts your arguments, why is the default position to spend billions of dollars on interdiction and incarceration?

The most direct evidence for effects can be seen in European countries with much more open drug laws and in this country with alcohol prohibition. Both examples point to interdiction and incarceration being counterproductive.

Even if one accepts your arguments, why is the default position to spend billions of dollars on interdiction and incarceration?

The most direct evidence for effects can be seen in European countries with much more open drug laws and in this country with alcohol prohibition. Both examples point to interdiction and incarceration being counterproductive.

You raise a good point. I’m certainly open to alternative policy ideas but I want to see more analysis on alternatives. As I said in a previous comment, from a quiver of bad choices, I’m tentatively holding to the position that the Drug War is the least of the bad choices.

You make reference to European drug laws as being an alternative model. I’m all for examining such alternatives under properly controlled conditions. We can compare Danish drug use in Denmark to drug use by Danish-Americans in the US, in other words, we control for population variance so that we can isolate the conditions that arise simply from different drug laws. So, for instance, let’s say that we find that Danes who use drugs are 3x more likely to be beneficiaries of generous Danish welfare programs than are Danish Americans who use drugs. That might tell us to expect that laxer American drug laws will induce greater withdrawal from productive work and perhaps a greater reliance on social welfare spending. If we model this properly then we can compare the costs incurred in restricting drugs against the costs expected to arise from increasing our tolerance for drugs in society.

I’m completely willing to be swayed by good research and I’m not a moral crusader against drugs, so if the data actually suggests that embracing drugs in our culture will produce “less bad effects” than fighting to restrict the use of drugs and penalizing those involved, I’ll be OK with that.

Dr. Taylor forgets (maybe later he will add it in) the costs of hundreds of innocents shot and some killed by police raids. This hit home with me as one of my closest friends and I had gone to our local range one evening. We each went home separately afterwards. He was beat and put his guns away without cleaning into his safe. An hour later the police mistakenly raided his home. Suppose they raided earlier while he was carrying in his gear or while he was cleaning?

Another important cost, yet difficult to quantify, is the crime committed to acquire drugs. A very large chunk of burglaries and petty thefts are done to acquire money to buy drugs. A number of the convenience store robberies are done for such. Unlike alcohol, where crime is the result of consumption, drug crime is largely related to acts committed to finance the habit. If we know the cost of cocaine when distributed and sold on a free market, we can calculate some of that cost. As marijuana is pretty much a weed, its cost should be minimal.

Steve

Another important cost, yet difficult to quantify, is the crime committed to acquire drugs. A very large chunk of burglaries and petty thefts are done to acquire money to buy drugs. A number of the convenience store robberies are done for such.

That would be an interesting study to ponder. I wonder whether the intuitive case would actually be quantified, for as this graph shows the US burglary rate is surpassed by countries like Canada, Australia and the UK, which I presume have less intensive drug laws. The implication would be that absent drug law disparity the US is a more law-abiding nation than is generally thought.

Prohibitionists dance hand in hand with every possible type of criminal one can imagine.

An unholy alliance of ignorance, greed and hate which works to destroy all our hard fought freedoms, wealth and security.

We will always have adults who are too immature to responsibly deal with tobacco alcohol, heroin amphetamines, cocaine, various prescription drugs and even food. Our answer to them should always be: “Get a Nanny, and stop turning the government into one for the rest of us!”

Nobody wants to see an end to prohibition because they want to use drugs. They wish to see proper legalized regulation because they are witnessing, on a daily basis, the dangers and futility of prohibition. ‘Legalized Regulation’ won’t be the complete answer to all our drug problems, but it’ll greatly ameliorate the crime and violence on our streets, and only then can we provide effective education and treatment.

The whole nonsense of ‘disaster will happen if we end prohibition’ sentiment sums up the delusional ‘chicken little’ stance of those who foolishly insist on continuing down this blind alley. As if disaster wasn’t already happening. As if prohibition has ever worked.

To support prohibition is such a strange mind-set. In fact, It’s outrageous insanity! –Literally not one prohibitionist argument survives scrutiny. Not one!

The only people that believe prohibition is working are the ones making a living by enforcing laws in it’s name, and those amassing huge fortunes on the black market profits. This situation is wholly unsustainable, and as history has shown us, conditions will continue to deteriorate until we finally, just like our forefathers, see sense and revert back to tried and tested methods of regulation. None of these substances, legal or illegal, are ever going to go away, but we CAN decide to implement policies that do far more good than harm.

During alcohol prohibition in the 1920s, all profits went to enrich thugs and criminals. Young men died every day on inner-city streets while battling over turf. A fortune was wasted on enforcement that could have gone on treatment. On top of the budget-busting prosecution and incarceration costs, billions in taxes were lost. Finally the economy collapsed. Sound familiar?

In an underground drug market, criminals and terrorists, needing an incentive to risk their own lives and liberty, grossly inflate prices which are further driven higher to pay those who ‘take a cut’ like corrupt law enforcement officials who are paid many times their wages to look the other way. This forces many users to become dealers themselves in order to afford their own consumption. This whole vicious circle turns ad infinitum. You literally couldn’t dream up a worse scenario even if your life depended on it. For the second time within a century, we’ve carelessly lost “love’s labour,” and, “with the hue of dungeons and the scowl of night,” have wantonly created our own worst nightmare.

So should the safety and freedom of the rest of us be compromised because of the few who cannot control themselves?

Many of us no longer think it should!