Eduard Shevardnadze, Icon Of The Final Years Of The Cold War, Dies At 86

Eduard Shevardnadze, who became an icon of the last years of the Cold War as Soviet Foreign Minister under Mikhail Gorbachev and then President of his native Georgia,has died at the age of 86:

Eduard A. Shevardnadze, who as Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s foreign minister helped hone the “new thinking,” foreign and domestic, that transformed and ultimately rent the Soviet Union, then led his native Georgia through its turbulent start as an independent state, died Monday. He was 86.

Irakli Garibashvili, the prime minister of Georgia, praised Mr. Shevardnadze for his “important role in finishing the Cold War and founding a new world order.” Mr. Gorbachev issued a statement offering his condolences to the family of Mr. Shevardnadze, as did President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia.

Mr. Shevardnadze was a committed Communist from a Communist family who had spent his working life as a Communist official when Mr. Gorbachev called him on June 30, 1985 with an astounding proposition: Would he manage the foreign policy of one of the two most powerful countries in the world?

Flabbergasted, Mr. Shevardnadze stammered that he had no experience in diplomacy, other than playing host to foreign delegations as the top Communist official in the Soviet republic of Georgia. He had visited just nine countries and spoke no foreign languages. And shouldn’t the foreign minister be Russian?

“The issue is already decided,” Mr. Gorbachev answered, Mr. Shevardnadze wrote in his memoirs, “The Future Belongs to Freedom” (1991). Mr. Shevardnadze was to report to work the next day.

“The decision to make Shevardnadze foreign minister was the first obvious display of Gorbachev’s remarkable political creativity,” Robert G. Kaiser wrote in “Why Gorbachev Happened: His Triumphs, His Failure, and His Fall” (1991).

In his memoirs, Mr. Gorbachev, whose title was General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, said that “experienced people” had understood his thinking: He had assured himself “a free hand in foreign policy by bringing in a close friend and associate.”

Together, the two men revolutionized Soviet foreign policy. They withdrew troops from Afghanistan, where the Soviet Union had waged a fruitless war; negotiated treaties on medium-range and strategic nuclear arms; took military forces out of Europe and away from the China border; allowed the reunification of Germany; and accepted human rights as part of policy discussions.

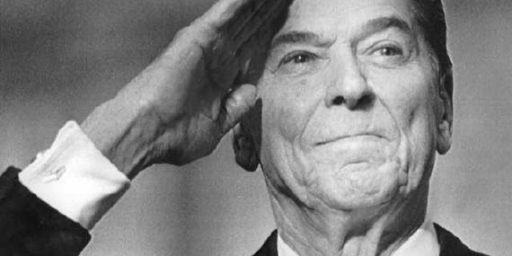

Mr. Shevardnadze was architect, spokesman and negotiator for the new policy, and the white-haired visage that earned him the nickname Silver Fox was nearly ubiquitous on the world stage from 1985 to 1991. The magazine The New Leader said in 2004 that his diplomatic accomplishments had been equal to those of Mr. Gorbachev and President Ronald Reagan.

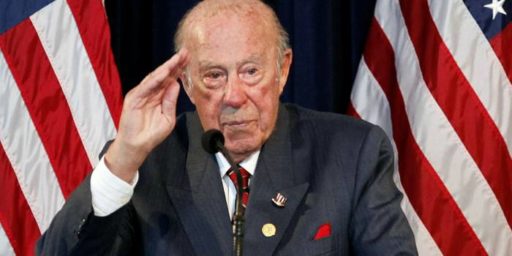

Part of his success was forging relationships with Secretaries of State George P. Shultz and James A. Baker III, who became proponents of reconciliation in administrations that were intensely anti-Soviet. Just as difficult, he helped convince Soviet hard-liners that it was time for rapprochement with the United States.

Mr. Shevardnadze was actually in the process of renouncing his Communist past. He had come to believe that the ideology was both wrong and doomed. In 1988, he was the first Soviet official to say that the clash with capitalism no longer mattered — an act of “true ‘sedition’ in the eyes of the official ideologues,” Mr. Gorbachev said in his “Memoirs” (1995).

Mr. Shevardnadze’s revisionist thinking was actually outpacing that of Mr. Gorbachev. “He thought he was refining socialism while I was no longer a socialist,” Mr. Shevardnadze told The New York Times Magazine in 1993.

Mr. Shevardnadze became worried that Mr. Gorbachev was increasingly falling under the influence of the hard-liners. He ultimately shocked his boss by resigning on Dec. 20, 1990, warning, “Dictatorship is coming.” After a botched coup attempt by hard-liners in August 1991, the Soviet Union dissolved itself on Dec. 26, 1991. It was the victim of economic chaos, political opposition from many of the constituent republics and chaos in the Kremlin. Three months later, Mr. Shevardnadze agreed to head the council governing Georgia after a coup there. He was elected president in 1995 and helped hold his country together, establish democratic reforms and stabilize the economy.

But his second term, won in 2000, was a disaster, as armed civil clashes proliferated, the economy deteriorated and cronyism and corruption flourished. He resigned on Nov. 24, 2003, after protesters’ chants of “Get out! Get out! Get out!”

The proximate cause of Mr. Shevardnadze’s fall was his involvement in rigged elections in 2002 and 2003, a violation of the electoral reform laws he himself had sponsored. His own Supreme Court invalidated the fraudulent elections.

In a television interview after being driven from office, Mr. Shevardnadze no longer spoke of perestroika or glasnost, the Russian words for rebuilding and openness that Mr. Gorbachev had popularized.

“It is not good to have too much democracy,” he said. “I think that was a mistake.”

Much like Boris Yeltsin in Russia, albeit for very different reasons, Shevardnadze’s post-Soviet career symbolized how and why it was so difficult to transition from 70 years of dictatorship to something resembling democracy, especially under the glare of the media. Leaving aside that part of his life, though, Schevardnadze deserves much credit for guiding the world to a peaceful end to a conflict that, for some 45 years, had carried with it a threat of devastating annihilation and, on at least one occasion, came close to crossing the line into just that. Shevardnadze replace Andrei Gromyko, who had served as Soviet Foreign Minister under every Soviet leader going back to Nikita Kruschev and, as the world soon learned, the change could not have been any different not just in tone but, eventually in policy. Along with Gorbachev, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and American diplomats such as George Schultz and James Baker, he helped bring to a peaceful end a conflict that very easily could have ended quite differently.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHylQRVN2Qs