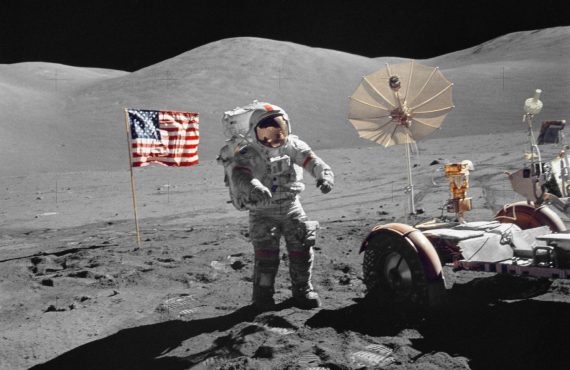

Eugene Cernan, Last Man To Walk On The Moon, Dies At 82

One of the few members of a small fraternity of heroes has passed away.

Eugene Cernan, the last man to walk on the surface of the Moon, died yesterday at the age of 82:

Eugene A. Cernan, the commander of the Apollo 17 lunar-landing mission in 1972 and the last human to walk on the moon, died on Monday in Houston. He was 82.

His death was announced by NASA.

A ferocious competitor with a test pilot’s reckless streak, Mr. Cernan (pronounced SIR-nun) rocketed into space three times, was the second American to drift weightless around the world on a tether, went to the moon twice and shattered aerospace records on the Earth and the moon.

He also slid down a banister on a visit to the White House and once crashed a helicopter in the Atlantic while chasing a dolphin. Skimming the lunar surface in a rehearsal for the first manned landing, he erupted with salty language heard by millions when his craft briefly spun out of control.

But he made spacewalks and romps over the lunar surface look routine, and in a way they were.

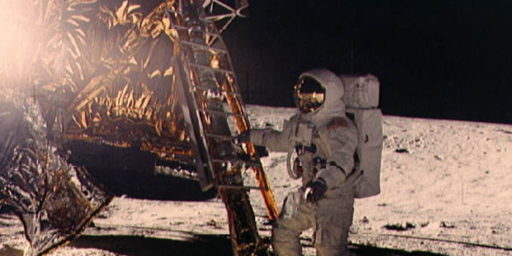

Three and a half years after Neil A. Armstrong took mankind’s first step onto the lunar surface in 1969, Mr. Cernan, a Navy captain and one of the nation’s most experienced astronauts, landed with a geologist-astronaut near the Sea of Serenity in the final chapter of the Apollo program, America’s audacious venture to fulfill President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 pledge to put Americans on the moon.

Captain Cernan was the last of 12 Americans to set foot on the moon in six Apollo landings. Two other missions were lunar orbital test runs, and Apollo 13 was an aborted landing after a malfunction. While Apollo 17 conveyed the drama of televised moonwalks, the awesome historicity of the Armstrong flight had faded, along with public interest in lunar missions that by 1972 had begun to seem repetitive.

Still, his mission was a technological triumph. While Ronald E. Evans, a Navy commander, piloted a command ship in lunar orbit, Captain Cernan and Harrison H. Schmitt, the first scientist to go to the moon, descended to the virtually airless, soundless surface in a four-legged lander that settled in a narrow valley of boulders and craters. After a 250,000-mile voyage from Earth, they put down 300 feet from their target.

“The Challenger has landed,” Captain Cernan announced in a broadcast to the world the Apollo crew saw hanging in the sky. “I’d like to dedicate the first step of Apollo 17 to all those who made it possible.”

He and Dr. Schmitt found themselves in a desolate but recognizable landscape near the Taurus Mountains and the Littrow Crater, a region of hills, cliffs and escarpments littered with tumbled rocks. After establishing a nuclear-powered base station, they set up scientific experiments and began three days of explorations on foot and in a battery-powered rover mounted with a television camera.

As color video pictures streamed across the gulf of space, the astronauts collected bluish-gray and tan rocks four billion years old, drilled eight-foot heat-probe holes and journeyed to a 7,000-foot mountain called the South Massif and to the edge of a deep crater. There they found a fumarole, an ancient vent for volcanic gases, and collected strange orange and red soil samples.

On three rover excursions that took them 21 miles to craters, rock slides and mountain walls, and in 22 hours of moonwalks, they collected 250 pounds of rocks and soil to carry home and left experiments that delivered data for years. The captain also scratched his daughter’s initials — TDC, for Teresa Dawn Cernan — in the lunar dust, a talisman that might last eons on a lifeless world.

The mission completed, the captain took his last steps on the lunar surface and spoke for posterity.

“America’s challenge of today has forged man’s destiny of tomorrow,” he said in words slightly garbled on recordings. “And as we leave the moon and Taurus-Littrow, we leave as we came, and, God willing, we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind.”

Dr. Schmitt climbed into the lander, followed by Captain Cernan. With a graceless farewell from the captain — “Let’s get this mother out of here” — the two astronauts blasted off and rejoined the orbiting command module. The trip back to Earth and the splashdown in the South Pacific, on Dec. 19, 1972, went like clockwork.

(…)

Eugene Andrew Cernan was born in Chicago on March 14, 1934, to Andrew Cernan, a supervisor at a naval installation, and the former Rose Cihlar.

He graduated from Proviso Township High School in Maywood, Ill., in 1952, and received an electrical engineering degree from Purdue in 1956 and a master’s in aeronautical engineering from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., in 1963. As a naval aviator, he logged 5,000 hours of flying time and 200 landings on aircraft carriers.

In 1961, he married Barbara Jean Atchley. They divorced in 1981. He later married Jan Nanna, who survives him, as do his daughter, Teresa Cernan Woolie; two stepdaughters, Kelly Nanna Taff and Danielle Nanna Ellis; nine grandchildren; and a sister, Dolores Riley.

Captain Cernan became a NASA astronaut in 1963. In his first spaceflight, Gemini 9 in 1966, he joined Col. Thomas Stafford of the Air Force on a three-day orbital mission testing rendezvous and docking procedures. He also circled the world twice as a tethered spacewalker. At 32, he was the youngest man to go into space.

His second spaceflight, with Colonel Stafford and Cmdr. John W. Young of the Navy in 1969, was Apollo 10, the final rehearsal for Apollo 11, which months later landed Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the moon. The eight-day Apollo 10 trip included a Cernan-Stafford descent in a lunar module to within eight nautical miles of the surface. It did everything but land. It also photographed landing sites and sent back the first live television pictures from the moon.

Captain Cernan’s final spaceflight, the capstone of the Apollo series, did not generate the worldwide excitement of the Armstrong-Aldrin adventure. But it did set records: the longest lunar landing flight (nearly 302 hours) and the longest lunar surface extravehicular activities (22 hours and 6 minutes). Captain Cernan also set a career record of 566 hours in space, 73 of them on the moon’s surface.

After Apollo 17, Captain Cernan helped develop the United States-Soviet project Apollo-Soyuz. In 1976, he retired from the Navy and NASA and became an executive of Coral Petroleum in Houston. He founded the Cernan Corporation, an energy and aerospace consultant, in 1981 and was chairman of the Johnson Engineering Corporation from 1994 to 2000.

Mr. Cernan, who lived in Piney Point, a suburb of Houston, contributed to ABC’s coverage of space-related news; narrated and was featured in documentaries; and wrote (with Don Davis) an autobiography, “The Last Man on the Moon,” published in 1999.

Cernan was a member of a small fraternity but, other than his media appearances, has been mostly the answer to trivia questions for the past forty years or so. Of the twelve men who walked on the lunar surface from Apollo program, six remain alive, including Buzz Aldrin from Apollo 11, Alan Bean from Apollo 12, David Scott from Apollo 15, John Young and Charles Duke from Apollo 16 , and Harrison Schmitt from Apollo 17. All of these men are in their eighties now, so it’s likely they’ll only be with us for a little while longer.

In later years, Cernan was a frequent television guest on broadcast and cable news networks to comment when events surrounding the space program were in the news. Most recently, he made headlines along with fellow Apollo astronaut Neil Armstrong, the first man on the Moon, when the two men appeared together before Congress and in the media to criticize the decision of the Obama Administration to cut back on what had been NASA’s plan to return to the Moon by 2020 as part of a broader effort for an eventual trip to Mars. Instead of following on previous plans, NASA and the Obama Administration chose to follow a plan that included abandoning the two decade old shuttle program in favor of developing a new launch vehicle that is supposed to be ready by 2020 at the earliest that would lead to an eventual return to the Moon at a future date, again as a prelude to what would hopefully be a trip to Mars that likely wouldn’t occur until at least a decade later. Cernan and Armstrong argued along with other former NASA astronauts and space enthusiasts that even a temporary end to American manned spaceflight would be a mistake. As a result of NASA’s decision, the only manned space missions undertaken by the United States have been those to the International Space Station, and for those the United States remains wholly dependent on the Russian Soyuz program, although NASA is also currently working with SpaceX and other private companies to develop a commercial manned spaceflight capability that could be able to transport Americans to the ISS before Project Orion, the current NASA launch vehicle program, is ready for use.

Here’s a clip from The Last Man On The Moon, a documentary about Cernan and Apollo 17 that was released to critical acclaim in 2014:

Rest in peace, Captain.

Very soon, we’ll be back to the point where no living human has walked on the moon.

Another true hero, gone.

RIP, sir.

He wrote a fine book, also titled “The Last Man on the Moon”. It includes some gentle jabs toward others (*cough* Jim Lovell *cough*) who had taken jabs at Gene in their books. Good stuff.

Sad to see some of my childhood/young adult heroes go. This always makes me think of the XKCD actuary table.

https://www.explainxkcd.com/wiki/index.php/893:_65_Years

These were brave individuals but, inspiring as it is, I’d much prefer to see more emphasis on unmanned flights – and more of them.

Life support systems add a ton of cost, weight and complexity to space missions – and lots of science never gets done because resources are exhausted by O2 generators, food and waste management and seating/cockpit function.

Mars rover is a great example of what can be done if we get humans out of the way.

OT But the CBO report today is a big deal. CBO