Geither: Defaulting on Debt Unconstitutional

The Obama administration is arguing the 14th Amendment renders the debt ceiling moot.

In our recent discussion over whether the 14th Amendment rendered the debt ceiling unconstitutional, commenter Andyman remarked, “I’d like to see someone from the administration (Geithner?) say something sympathetic about this line of thinking. Just to put the marker down that Obama isn’t ruling out just carrying on as if the debt ceiling doesn’t exist.”

Well, someone from the administration (Geithner!) has done just that:

At a Politico Playbook breakfast on May 25, Geithner was asked by host Mike Allen about the negotiations over default and the debt ceiling.

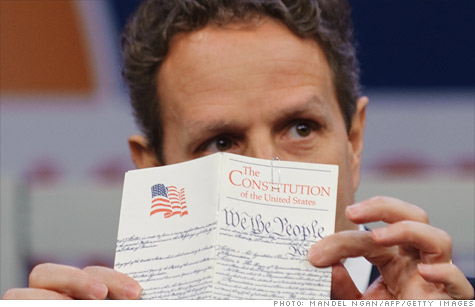

“I think there are some people who are pretending not to understand it, who think there’s leverage for them in threatening a default,” Geithner said. “I don’t understand it as a negotiating position. I mean really think about it, you’re going to say that– can I read you the 14th amendment?”

Geithner whipped out his handy pocket-sized Constitution. Allen tried to brush it aside. “We’ll stipulate the 14th Amendment,” he said.

“No, I want to read this one thing,” Geithner insisted.

“It’s paper clipped!” Allen observed, noting that Geithner’s copy of the Constitution was clipped so that it would open directly to the passage in question.

“‘The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for the payments of pension and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion’ — this is the important thing — ‘shall not be questioned,” Geithner read.

“So as a negotiating strategy you say: ‘If you don’t do things my way, I’m going to force the United States to default–not pay the legacy of bills accumulated by my predecessors in Congress.’ It’s not a credible negotiating strategy, and it’s not going to happen,” Geithner insisted.

Now, as with many constitutional provisions, this clause is subject to interpretation. But Jack Balkan’s essay on “The Legislative History of Section Four of the Fourteenth Amendment” makes a persuasive case that Geithner is on firm ground. It’s worth reading in full but here’s a taste:

Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio was a leader of the Radical Republicans and the President pro tempore of the Senate. He agreed with Howard’s reasons for why the Confederate debt should be repudiated, but he argued that if the concern was to avoid future disruption of American politics, the current proposal did not go far enough. It was also necessary to guarantee the Union debt, because former rebels or rebel sympathizers who returned to Congress after the war might, out of selfish or malicious motives, seek to prevent Union soliders and their widows from being compensated. Moreover, there was no guarantee of what a later Congress, motivated by different priorities, might do. Shifting majorities in a future Congress might be willing to sacrifice the public debt or the interests of pensioners in the name of political expediency. Thus, it was as important to guarantee the Union debt as it was to repudiate the Confederate debt.

[…]

If Wade’s speech offers the central rationale for Section Four, the goal was to remove threats of default on federal debts from partisan struggle. Reconstruction Republicans feared that Democrats, once admitted to Congress would use their majorities to default on obligations they did disliked politically. More generally, as Wade explained, “every man who has property in the public funds will feel safer when he sees that the national debt is withdrawn from the power of a Congress to repudiate it and placed under the guardianship of the Constitution than he would feel if it were left at loose ends and subject to the varying majorities which may arise in Congress.”

Like most inquiries into original understanding, this one does not resolve many of the most interesting questions. What it does suggest is an important structural principle. The threat of defaulting on government obligations is a powerful weapon, especially in a complex, interconnected world economy. Devoted partisans can use it to disrupt government, to roil ordinary politics, to undermine policies they do not like, even to seek political revenge. Section Four was placed in the Constitution to remove this weapon from ordinary politics.

That strikes me not only as a reasonable reading of the Constitutional but a prudent principle of public policy. But, again like many provisions of the Constitution, there’s no specification on the mechanism as to how it should be enforced. Undermining the notion that the Executive has the right to ignore laws that stand in the way of default–in this case, the debt limit–is the next line in the Amendment:

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Rather clearly, it is the legislature, not the executive, which has the responsibility to act. What if it abrogates that responsibility? Presumably, the president can do what presidents do: Act and dare the legislature to do something about it. Impeachment is unlikely, even with a Republican House. And the courts would almost certainly see this as a “political question” and stay away.

The only reasonable interpretation of Section Four seems to me to be the one that says that the President has the authority to make sure that debt obligations are paid, even if that means not paying any other government obligations or expenses (including salaries). The argument runs into a problem when you get to the point where it’s claimed that the President also has the authority to incur new debt even if there isn’t a statutory authorization for same.

If nothing else, this entire argument demonstrates how utterly silly the whole “debt ceiling” idea actually is. We’re creating a financial, and now potentially Constitutional, crisis because of a law that no other nation in the world has ever even considered.

Creating a financial crisis is the entire point. Republicans thought that they could get leverage by creating risk that failure to heed their demands would push the global economy back into recession.

Obama should simply refuse to default, and take whatever measures are necessary to pay government obligations including issuing new notes if necessary. The courts won’t intervene due to political question/lack of judicial remedy issues. Moreover, any attempt to impeach Obama would be pretty insane. The optics are all wrong, and there’s a lack of a clear message: “Obama ignored Congress, and relied on a Constitutional provision to pay for the debt our tax cuts incurred!”

It would also probably produce a better debt deal, insofar, as it might be less tilted towards Republican demands to reduce expenditures on the middle class while demanding nothing from corporate and economic elites.

There’s something that puzzles me: how can the debt ceiling (an act of the legislation) and Congress appropriating funds that exceed the debt ceiling both be constitutional?

Let’s see how many wishes I have left. I’d like to see someone from the administration (Locke?) hand out Porsches to internet commenters…

@Dave, I don’t think it’s a constitutional issue; I think the question is how can they be consistent?

I think a problem with the Constitutional argument, is that “validity” is a more limitted concept than default. I don’t think the government is necessarily precluded from, let’s say being one day late with a payment, a condition that would clearly be considered a default from the creditor’s p.o.v., but does not challenge the validity of the debt. From there, the possiblities are endless.

Bachmann has been vocal about ignoring the debt ceiling. This must be what she meant…because as a constitutional scholar she would know this. And as a conservative she wouldn’t advocate not paying debt incurred…right?

Q: Do you “question” that you owe $100,000 on your home mortgage?

A: Nope.

Q: Are you able to pay it?

A: Nope.

Neither the plain text, the original meaning, nor the original intent of A14-4 support this nonsense.

It’s important to understand the historical context of Section Four, and why it was put in the Amendment.

The concern was that when, at some point, the Southern states again sent Senators and Congressmen to Washington, they would be able to use their political power (which would still be quite formidable) to repudiate the debt that the United States had incurred during the war, or to make the U.S. responsible for all or part of the CSA’s debt in the same manner that the United States assumed the debts of the colonies. Section Four was meant to make that impossible.

The suggestion that it was ever intended to give the President the power to essentially ignore Congress on fiscal issues doesn’t seem to me to have any real support.

Let me expand on my thought a bit. Forty-odd years ago the Supreme Court found that the Executive did not have the power to refuse to spend what the Congress had appropriated. IMO the Court decided rightly.

If revenues do not reach what the Congress has appropriated, the only alternatives are for the Executive to refuse to spend or to borrow to make up the difference. If the Executive does not have the power to refuse and the Congress has the power to require spending that exceeds revenues, then, implicitly, the Executive has the power to borrow.

An alternative might be that any Congressional appropriations that exceed actual revenues are null and void.

@Dave Schuler: Article I, Section 8 enumerates, among the Powers of Congress,

So, clearly borrowing is a power of the legislature. And “debt” does not appear again until Article 6; it’s nowhere listed in the two articles addressing the Executive and Judiciary.

So it says we have to pay our debt. That Congress can’t repudiate it. But the executive isn’t able to expend funds not appropriated. So I’m not sure how that makes it possible for Geithner to just blow off the debt ceiling. So if the debt ceiling prevents further borrowing to rollover the debt, we’ll just have to cut all expenditures that are not paying interest or principle. A decidedly ugly scenario, I’ll admit, I believe it is called, austerity, in Greek.

Of course, that means, massive lay offs, withholding grants, suspension of contracts, no more Medicare or Medicaid new claims. And this is where it gets ugly, no Social Security payments since the SCOTUS has ruled that there is no claim to those payments so it can’t be debt. But of course, first, no boondoggle trips for the president to Martha’s Vinyard since such travel requires massive expenditures for government employee support and protection.

Which is worse, default or ignoring the debt ceiling? That’s not a totally legal question. If the real-world effects of default are so severe, then some way will be found to avoid it, with a plausible legal argument added as window dressing.

When two laws are in conflict, the more recent law is generally considered to take precedence. Since the continuing resolution was passed after the most recent setting of the debt level, I’d argue that the president was already authorized to exceed the debt ceiling up to the amounts authorized in the continuing resolution.

@Dave, I assume the SCOTUS was faced with spending that the Congress had appopriated money for. If Congress mandates spending without funding it, I think Congress has passed on to the executive the discretion to do what he can; defer some spending projects for later years. The contrary argument, that unfunded spending gives rise to a Presidential power to borrow or tax without Congressional authorization would seem inconsistent with the Constitution, whatever the Fourteenth Amendment says.

(This is the way it’s handled at the state level, and as far as I know it doesn’t raise concerns under the contract clause that the state is repudiating contractual obligations)

@James:

That’s begging the question. Perhaps I stated my expansion clumsily. The issue is the debt ceiling. I’m suggesting that by authorizing the spending in excess of revenue Congress is implicitly borrowing.

@Dave Schuler: Ah, I see what you mean. Under that interpretation, Stormy Dragon would be correct. The debt ceiling is mere legislation, so any subsequent legislation that exceeded the debt would nullify the ceiling.

I’m not sure that’s dispositive. As noted, the Constitution vests the borrowing power in Congress. If the normal mechanism for that is that Congress authorizes and arranges for a loan, then I don’t see how the president takes that upon himself. If, however, the normal mechanism is for the Treasury to facilitate the loan, it would just be ordinary business.

Dave, I don’t think Congress authorizes spending in excess of revenue:

It passes laws requiring spending;

It passes laws providing for taxes and borrowing.

While the spending is usually fixed, the income produced from taxes is uncertain and depends on what is collected. The mundane point here is at the moment spending is authorized, you can’t say it would exceed government revenue.

I understand the debt ceiling as an open line of credit, authorizing the executive to sell treasury bonds up to a certain amount to cover any shortfalls that occur. That might just be smoothing of irregular income streams, or it might be shortfalls frorm reliance on rosy scenarios. But how can the government borrow more than the legislature authorized?

The thing is, if the administration takes the position that the debt ceiling must be followed, It then must pick and choose what programs and agencies to fund and which not to fund. This is essentially a line-item veto, which I would argue is a larger insult to congressional power than the executive ignoring the debt ceiling.

If the executive ignores the debt ceiling Congress can simply ensure any future debt ceiling and appropriation bill match, thereby solving the problem. But if the executive claims a defacto line item veto, all legislative deal making goes out the window when the opposite party realizes that the president can simply not honor any funding compromises.

I’m pretty certain Republicans in Congress are hoping that Obama take this stance and ignore that the debt limit hasn’t been raised. They will then use it for new attacks on Obama and they will not have to face the effect of a default on the debt.

Only way that all this might end up as a victory for the Democrats is if there’s an actual default. Not sure that’s a victory the Democrats would want, or anyone else.

I doubt voters in general are informed enough about effect that a default will have, they aren’t going to reward Obama for avoiding it.

It’s pretty clear that there’s no adults among Republicans in Congress.

The problem with the Stormy Dragon argument is that if the inability to pay obligations on the public debt allows the President to disregard laws that are old, then the President could ostensibly invalidate the Bush tax cuts without Congressional approval, couldn’t he?

I’m not sure any of this is going to change Republican behavior on the debt ceiling. They have already decided that the debt ceiling and the prospect of US default is fair game for negotiating. So long as people continue to erroneously believe that the debt is only a spending problem, and not a revenue problem or not even some combination of the two, than the optics remain good for the Republicans, who can essentially say:

“We’ve already agreed to increase the debt ceiling, we just need to get the evil Democrats to take tax increases off the table, it’s a spending issue, we need to cut more spending so we don’t incur further debt, they just want to increase taxes so they can spend more which will only put us further into debt.”

So lets say the Obama Administration threatens to ignore the debt ceiling, citing it as unconstitutional, how does that threat change the optics for Republicans?

Does it give Republicans more cover in their hard line stance by taking away the threat of a default?

Does it give the Republicans more ammunition against the President? “Runaway President ignores Congressional negotiations on the debt to keep spending levels high and tax increases on the table.”

So basically, in what sense does laying this out there as an option do anything to change Republican behavior? Or does it only further encourage more of their brinkmanship?

To be clear, I’m not saying if Congress fails to get a deal that the Administration should let the US default, I’m just wondering what good it is for them to make clear at this point that Republicans have cover for sticking to their guns.

I think there’s a big difference between resolving the contradiction via a normal process (the issuance of bonds by the treasury) and via something the executive branch has never had the authority to do (change tax structure).

@Doug Mataconis: Actually the Executive branch is suppose to support the constitution and enforce all laws. If the debt ceiling is unconstitutional then Obama must take it to the Supreme Court. The fact that no other President questioned the Debt ceiling is odd… they didn’t just discover the Constitutional implications… I actual am surprise after all the political use of the budget and debt for decades this is the first I am reading about it. It’s my fault for not looking at the Constitution, but law makers had to know there was an issus at play here.

No other president was put in a situation of congress authorizing appropriations, but then denying the debt to cover them.

I think the proper response to the unprecedented GOP demands regarding the debt ceiling is to only negotiate for a complete repeal of the debt ceiling, so this shouldn’t happen again. The debt ceiling doesn’t make sense, if Congress doesn’t like the debt they can raise revenue or cut spending, there’s no sense in having a separate debt limit.

All that matters is how the Supreme Court will respond and they will respond the way the Chamber of Commerce and Wall Street wants them to respond. Yep – it will be found unconstitutional.

What would happen if the administration then decided they would not pay for any programs (infrastructure projects, postal delivery et al) in districts represented by House Republicans?

Could it be argued that by charging the Department of the Treasury (an agency of the executive branch) with management and servicing of the debt, Congress has implicitly granted such authority?

@JKB:

But that is the point, they WERE appropriated. The debts were appropriated when the budget passed. This debt ceiling authorization is a strange deal. Congress appropriates the money to be spent when the the budget passed but now says, no we wont pay it. Like ordering your meal and after you eat, saying you are not going to pay for it.

I admit, I do not understand this. How come the republicans are so gung ho to not pay the debts now but were not gung ho about cutting the spending when they did the budget. THAT is when you cut spending, when you pass the budget.

@Scott F.:

Man I would really hope Obama has the guts to do that. Shut down all the Fed programs in Republican districts first but I doubt he does.

I have read some places where tax loop holes are actually authorized as spending items. If true then the president would be able to close tax loop holes as part of the emergency powers. That could get interesting.

I actually think the 14th amendment gets the republicans out of a jam here. If it was not for the 14th amendment then they would be granting the executive branch dictatorial power over the budget. The money HAS been authorized by the budget process. If the president can close loop holes then he can raise revenues.

But the 14th amendment means that we just ignore the debt limit, the budget is what matters and what ever congress authorizes gets spent.

@Dave Schuler, there is no rule that laws have to be mutually consistent. They should be for sure, and if they were, the debt ceiling would always track the legislated tax and spending levels.

Overall, I’d say the Administrative Branch would have a responsibility for triage, in event of any financial calamity. They would probably use what credit lines they have available, and that is probably much more complicated than any of us here could fathom. And I’d fully expect some high profile “austerity” moves.

Actually, I’m coming around to a new opinion with respect to 2012. I still see it as a referendum on tax, and that Democrats and Republicans are both delaying as much as possible, killing time until that vote.

But now I’m beginning to suspect a worse subtext. That is, that both parties see full austerity as a necessity, but neither wants to say something so sad, so pessimistic, before the 2012 election cycle.

So both parties will pretend solutions, pretend that the outcome will be easy for voters, until whoever gets elected … and then it will be “whoops, we have less money than we thought,” and (with or without small tax increases), it will be austerity.