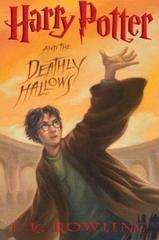

Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows

I wanted to have this posted in a more timely fashion but, between starting a new job and a hard drive crash that kept me offline for over a week, it ended up on the backburner. Nevertheless, for that as might be interested, here’s my review of the final Harry Potter book.

I wanted to have this posted in a more timely fashion but, between starting a new job and a hard drive crash that kept me offline for over a week, it ended up on the backburner. Nevertheless, for that as might be interested, here’s my review of the final Harry Potter book.

I won’t go as far as Sophie Masson and say that Harry Potter is the best fantasy series ever. But it is delightful, engaging, and compelling. Yes, they’re intended as juveniles but, in the tradition of the best such works (Narnia and Earthsea being the most obviously relevant examples), are eminently enjoyable by adults, as well. One finds oneself increasing attached to the characters and concerned for their fates. The end of the series is accordingly leavened by the bittersweet realization that one won’t get any further opportunities to spend time with these wonderful people.

Perhaps most importantly, now that it’s all said and done, the moral lesson of the series is neither trite nor obvious but, rather, important and thoroughly developed.

*** SPOILERS BELOW – READ ON AT YOUR OWN RISK ***

Turning to this last point first, note that it is especially significant because the first indications of the lesson being taught appeared in the early books suggested that we were in for just one more in an endless series of “Love conquers all” morality plays. That’s certainly the core of it but, as with other aspects of her tale, Rowling’s real point is considerably more nuanced.

The lessons we teach our children (and this series has certainly taught a lot of them) are of vital importance. The idea that “popular” works can also serve this function is often discounted, but the lessons embedded in such works are arguably among the most important, since they reach so many. Trust, loyalty, bravery, honesty, humility, courage in one’s convictions… these are the lessons that Harry Potter teaches. Love does indeed conquer all, but it doesn’t do so painlessly. On the contrary, love often demands very heavy sacrifices indeed. In the end, however, they tend to be worth the cost.

The parallels between himself and Voldemort, first seen upon Harry’s visit to Olivander’s in Chapter 5 of Sorcerer’s Stone, emphasize how easy it would have been for Harry to go the same way as the Dark Lord. As we discover how he gained some of his powers and the various ways he and the Dark Lord are alike, the crucial distinction between them grows ever more important. Fate shapes us, but it’s what we do with what fate gives us that makes us who we are. Harry is frequently reminded of his similarities to Tom Riddle/Lord Voldemort, but his capacity to give and receive love (which Voldemort utterly fails to comprehend, making him evil) and the choices he makes as a result are what make him good.

This is underscored all the more forcefully when we learn what Snape’s really been up to all this time and why. As is her wont, Rowling leaves Snape’s true allegiance ambiguous as long as possible. But when we do finally learn his backstory — which turns out to be a rather more robust and interesting tale than I think most of us truly expected — Snape’s redemption arises from the same source: His capacity to love. Snape is a genuinely flawed (his pride caused him to ruin whatever relationship he might ever have had with Lily, for instance) but, while his beliefs led him to follow Voldemort, his love for Lily redeems him, leading him down the most dangerous and difficult path of any character in the series. Yet he does it and seems genuinely shocked when he discovers, or so he thinks, that it’s never been to “save” Harry at all.

Which leads us to Dumbledore. Even after his death Dumbledore guides those who “serve” him, often by outright manipulation. But, we discover, he really does know what he’s doing. Dumbledore’s final manipulation, via Snape’s memories, is intended to ensure that Harry is saved. We share Snape’s anger at Dumbledore’s intentions until we discover the real reason behind it, something we’ve been well prepared to do by the way Rowling leads us to that particular circumstance. In the end, however, the trust Dumbledore places on both Harry and Snape — and they in him — is as prescient as his gift to Ron.*

In the end, pretty much all the open questions are answered, most of them satisfyingly. Some people don’t make it to the end, which was to be expected. Rowling’s never shied away from killing characters when the plot demands it. Here, all of his substitute parents dead, Harry ends the story standing fully on his own two feet.

Other characters come into their own, as well, Neville Longbottom, most especially. That he took the lead among the students in Harry’s absence and was able to prove himself a “true Gryffindor” in the climax were especially rewarding. Ron and Hermione play a more central role in the resolution of the plot than they’ve been allowed to for some time, moving up somewhat from the more supportive roles they’ve fulfilled the last few books to actively participate in destroying Voldemort’s horcruxes (letting each of them, plus Neville, destroy one was a nice touch that underscored the fact that, without the help and support of his friends since Year One, Harry would never have made it this far).

There have been a lot of questions raised about just how much of the series Rowling really had planned out from the start. Well, I’ve reread a couple of the earlier books since finishing this one and I have to conclude that she wasn’t just winging it: The groundwork for almost every single major element of the climax of Deathly Hallows is laid in the closing chapters of Chamber of Secrets. She took us on a long, emotional — and very entertaining — journey to fill in the details on the way from from there to here. And taught some valuable lessons along the way.

—

* I note, however, that there’s a rather large plot whole in the Dumboledore-Snape-Harry dynamic: The only way that Snape could transmit the information Dumbledore needs Harry to get from him that would lead Harry to actually believe that information is the way it happened. But not even Dumbledore is prescient enough to know that Harry would just happen to be ready to hand under his Invisibility Cloak when Voldemort attacks Snape or that Voldement would just happen to walk away leaving a mortally wounded Snape just enough time for Harry to get the memories from him. It works very well as plotted, true. And Snape is clearly trying to follow Dumbledore’s instructions in asking to be allowed to go find Harry right before Voldemort sets Nagini on him. But we’re never told how Snape was supposed to overcome Harry’s immense distrust if events had turned out any other way.

Another plot problem arises with Harry’s plan to end the extraordinary power of the Elder Wand. Dumbledore apparently became the Wand’s master by defeating its previous possessor, Grindelwald, in a duel. But Grindelwald can’t have been the Wand’s master: He stole it, rather than defeating its master (plus, he should’ve been unbeatable with it). So, unless the Wand chose Grindelwald as its master anyway and Grindelwald fought Dumbledore with some lesser wand for some reason (which is hard to believe), the Wand has at least once chosen a new master after passing out of the hands of an old one without that master being defeated. It can do so again, making Harry’s plan unlikely to work.

There are other odd plot holes here and there in the series, but overall I enjoyed the books, and very few works of fiction end up perfectly written without any holes.

I think one thing I liked about the last book, is up until the 7th book, Rowling leads the reader and the various characters to believe the Voldemort is very powerful and clever, but in the end his pride in his cleverness is what killed him.

All too often people who end up powerful fail to see their own weaknesses, and Voldemort’s pride in himself pretty much killed him.

I think I enjoyed the transformation of Neville from the clumsy and scared boy into the strong young man of the 7th book as much as any other character.

How old are you, 12? This is a kid’s book, that’s all. Adults who really aren’t readers and with limited literacy love the series. But why is it these adults always have to compare Harry Potter to great literature? Great literature that they’ve never even read, of course. Harry Potter is to Lord of the Rings as a recorder is to a Stradivarius.

There is one great thing about this series though, for all you low intelligence adults that love the book: you can start at the beginning and read it all over again since you probably forgot it all anyway! lol

What snobbery.

So exactly what qualifies something as “great” literature?

Keeping in mind of course, that a lot of what we currently view as “great” literature was viewed as contemporary fluff when it was published.

Wow. That’s a reaction I didn’t expect. I’d lay odds I’m much better read than you are, Christopher, along with a great many people who love this series. It doesn’t sound like you’ve read it, which would render you rather ill-equipped to judge its merit. Judging what you know little or nothing about is the hallmark of a bigot, not the highly literate and intelligent.

In any event, nothing in my post calls HP “great literature.” The closest I came was to compare it favourably with the Narnia and Earthsea books. Since I’ve read them all, I know it to be a fair comparison. Other than that, I called them delightful, engaging, and compelling juveniles which are eminently enjoyable for adults, as well. And, as they are juveniles, I also focused in particular on the moral lessons they’re teaching the millions of young people who’ve read them, a topic I presumed would be of interest to at least some of OTB’s readers.

A person truly interested in the literary arts would celebrate HP, even if he didn’t particularly care for the genre, for having very likely turned thousands of young people who might not otherwise have been into readers. Your intemperate remarks just mark you out as one of those insufferable prats for whom anything that becomes popular must perforce be bad.

Do not feed the troll.

Yea, I did. I suffered through them. I read the books. To my children! I guess that clears me of being a bigot lol.

As far as “intemperate”, well, I guess I am intemperate of HP. And hey, I think the books are great for kids, I guess. But I hope they read good literature, such as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl, or Half Magic by Edward Eager or numerous other fantastic books out there.

The fact is, in 10 years HP won’t make any noteworthy critic’s top 20 list for any kind of category.

To Christopher:

You claim to be a well read adult. And, while you may have read some literature that is considered great by the standards of many, I wonder how many well read adults use “lol” when typing. Putting your typing deficiencies aside, however, the fact remains that there is no formula for great novels. And because there isn’t a specific recipe for a “classic” or any other kind of recognition a book can receive, it all comes down to opinion. So, while YOU may think Harry Potter sucks, you are in the minority. And though “minority” doesn’t always mean “wrong”, I know if I started insulting the plot or questioning the validity of “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory” (which, by the way, is the real name of the book. Not “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. That’s the name of the movie), you would be more than happy to argue and tell me why it’s a classic and all that other stuff, but the reason it’s a classic is because tons of people liked it. Likewise with Harry Potter, tons of people like it. And you may not be one of them, but that doesn’t really matter. So, in 10 years, we’ll see what makes the top 20 list, but I’m betting that “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory” won’t make the cut.

Let’s face it, life is one continuous plot hole.

WRTO Voldemort: Just finished David Eddings’ Magician’s Gambit wherein the villain does himself in through a very stupid mistake. One he has time to heartily regret. 🙂

WRTO Reader Maturity: Thank you, Christopher. Your childish rejection of the series has persuaded me to pick up the books when I have the money. (I would not complain if the paperback editions were to show up at my apartment door, but be sure to wait until book 7 is out in paperback before you send them my way. 🙂 )

I read the first book back in the long ago. I’ve read better, I’ve read worse, but the worst reason for not reading something is because it’s “immature”. My first criteria is, is it a good read? All else follows from there. I’ve read one book of the adventures of Captain Underpants. It was silly, it was non-sensical, it was good. The CU books teach you more of the mind of the eight year old than most child psychology books. And they’re written for kids and adults to share.

So the HP books aren’t “proper literature”. At least people are reading them. The important books aren’t doing it, why not something socially inconsequential?

Speaking of HPs. The stories of HP Lovecraft are starting to enter literature courses around the world. How long until post grads present their thesis defense concerning the existentialist permutations of “Cthulhu ftaghn”?

I sometimes think Dave Pilkey somehow got stuck at age 8, because you are right that he definitely captures the thinking of 8ish year old boys in CU and his other children’s books are also on target.

JEG does make a good point-what is “good” with regards to books and literature is very much in the eye of the beholder. Thomas Hardy is considered “good” literature, but after being subjected to his works twice in various lit classes over the years, I would rather poke needles in my eyes than read anymore voluntarily.

My oldest daughter didn’t care at all for the Harry Potter books. That’s fine, she enjoys reading other types of books, and that kind of fantasy wasn’t her thing. My other daughter and older son have both spent time reading the books, and my daughter has read and reread the series. She also reads Poe, Twain, and spent some time with Roald Dahl.

Whether the series is “great” or not is definitely subjective, but it certainly has themes that have long been a part of fantasy fiction, and can be fun to discuss.

I think you’ve made a mistake on what it means to “defeat” another wizard where the Elder Wand is concerned. In the story of the Deathly Hallows (in the book, not the book by Rowling) the brother who recieved the wand from Death was killed by having his throat slit. Harry “defeated” Malfoy by grabing the wands out of Draco’s hand. Hence I don’t think defeat is something simple as being defeated in combat.

As for Dumbledore facing Grindelwald, again, the Elder Wand is supposed to be very efficacious when facing death. If Dumbledore dueled Grindelwald without trying to kill him the benefit of the wand might be minimized or even eliminated. This fits in well with Dumbledore’s comment to voldemort, IIRC in Order of the Pheonix, that there are worse things than death. To Voldemort death was the worst possible outcome–hence all his horcruxes. This obsession by Voldemort is even more ironic when one stops and considers that is was Harry and his mother’s defeat of Voldemort that starts off the series. Even after that, Voldemort still fears death above all else. And also keep in mind Ollivander’s comment about wandlore, that it is a complex area in magic and that it is not well understood. In short, there is the “its magic” explanation which renders rational explanations problematic (okay so it is also a bit of a dodge too).

And the “unbeatable” nature of the Elder Wand is probably exaggerated. This point is made when Harry considers pursuing the Deathly Hallows vs. the horcruxes, but rejects that notion and returns to finding and destroying the horcruxes.

As for Harry trusting Snape, I think that was the point of the memories. Snape would have given them to Harry and Harry would have believed them just like the last time he believed Snape’s memories. I think that was the plan, that at the end Snape was to find Harry, give him the memories. Granted it was a risky part of the plan, but I don’t see how risk could have been entirely eliminated in any plan when dealing with Voldemort.

Here is the fully exchange between Dumbledore and Voldemort in Order of the Phoenix.