Internet Ruining Civil Society!

John Hawkins explains “How the Internet Damages Our Culture,” arguing “American society as a whole, and politics in particular, has become considerably ruder, cruder, and more paranoid than it used to be.” Stacy McCain counters that the Internet is just going where television has already taken us.

John Hawkins explains “How the Internet Damages Our Culture,” arguing “American society as a whole, and politics in particular, has become considerably ruder, cruder, and more paranoid than it used to be.” Stacy McCain counters that the Internet is just going where television has already taken us.

I challenge the premise.

There’s no doubt that our popular discourse is cruder in some ways — the acceptable use of profanity in public spaces, for example — than it was even when I was a kid. On the other hand, we’re less rude in crude in other ways, such as our expression toward women, racial minorities, homosexuals, the mentally ill, and others.

The complaint that our politics is less civil than it once was is, well, as old as our politics. Scan through, for example, David Shields‘ Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (1997).

Like the 1990s, the 1790s were obsessed with civility — in terms of cultural adequacy compared to Europe, in reaction to the rancorousness of politics, in contrast to the rudeness of native peoples, and in terms of the relations of the sexes in public places (xxi).

The 1990s were indeed apparently obsessed with civility, as George James published a NYT oped the same year on “The Vulnerable History of Incivility.” He reminds us that,

When Alexis de Tocqueville toured America in the mid-1830’s, Professor Barber said, he was impressed with ”the local spirit of liberty” and the ”powerful participation” of citizens in local government, whether at a New England town meeting or a gathering of settlers at a frontier fort.

He quotes Benjamin Barber:

”Divisive rhetoric has become not only disagreement between parties but a rejection of the legitimacy of the other side, validating a position that your opponents are immoral, un-American and possibly worthy of being subjected to violence,” he said. Opponents become ”enemies of the Republic and the political process itself.” Professor Barber added, ”We’ve seen the results at abortion clinics, in the far right militia movement and in Oklahoma City.”

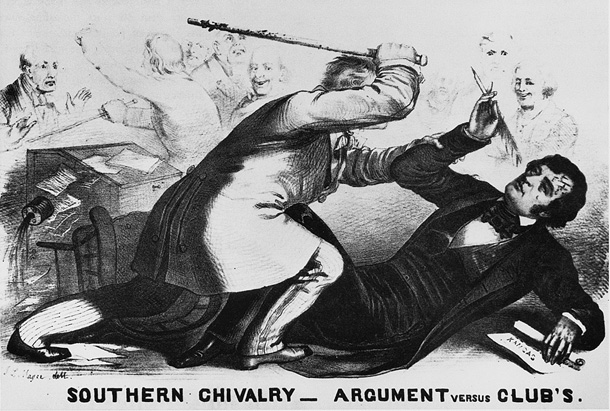

While that sounds ominous, one only has to recall the frequent rioting and lynchings of the colonial and immediate post-colonial period for perspective. Similarly, the illegitimacy of opponents was hardly invented a decade ago, as the viciousness of the 1800 presidential campaign, canings on the Senate floor, the Nullification movement, and the Civil War make clear.

Indeed, James Parton‘s account of “The Presidential Election of 1800,” written in the July 1873 (no, that’s not a typo) Atlantic Monthly, is quite instructive.

That product of the human intelligence which we denominate the Campaign Lie, though it did not originate in the United States, has here attained a development unknown in other lands. It is the destiny of America to try all experiments and exhaust all follies. In the short space of seventy-seven years, we have exhausted the efficiency of falsehood uttered to keep a man out of office.

[…]

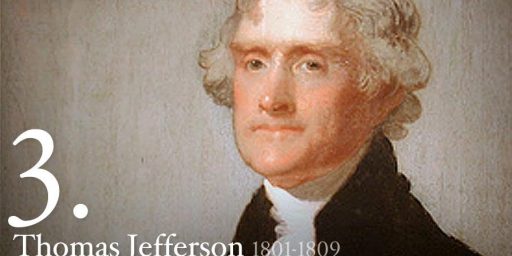

Thomas Jefferson, who began so many things in the early career of the United States, was the first object upon whom the Campaign Liar tried his unpracticed talents. The art, indeed, may be said to have been introduced in 1796 to prevent his election to the Presidency; but it was in 1800 that it was clearly developed into a distinct species of falsehood.

[…]

He was able, of course, to prove that Mr. Jefferson “hated the Constitution,” had hated it from the beginning, and was “pledged to subvert it.” The noble of New York (Hamilton, apparently) writing in Noah Webster’s new paper, the Commercial Advertiser, soared into prophecy, and was thus enabled to describe with precision the methods which Jefferson would employ in effecting his fell purpose. He would begin by turning every Federalist out of office, down to the remotest postmaster. Then, he would “tumble the financial system of the country into ruin at one stroke”; which would of necessity stop all payments of interest on the public debt, and bring on “universal bankruptcy and beggary.” Next, he would dismantle the navy, and thus give such free course to privateering, that “every vessel which floated from our shores would be plundered or captured.” And, since every source of revenue would be dried up, the government would no longer be able to pay the pensions of the scarred veterans of the Revolution, who would be seen “starving in the streets, or living on the cold and precarious supplies of charity.” Soon, the unpaid officers of the government would resign, and “counterfeiting would be practiced with impunity.” In short, good people, the election of Jefferson will be the signal for Pandora to open her box, and *empty* it upon your heads.

Blame it on the Internet, I suppose.

@reader_iam Joyner provides Hawkins with a bit of historical background: http://tinyurl.com/czvr4o

I think that John’s premise is fatuous. As long as we’ve got Jacksonian democracy here which we’ve had for nearly 200 years it’s going to be rough and tumble.

As to the Internet, generally, and the blogosphere in particular I don’t believe there’s a great deal that’s novel in their tone or style. The more reasonable bloggers tend to take their tone and style either from the New York Times and the New Yorker (for the more temperate Left Blogosphere), from various alternative print journalism (for the more outrageous Left Blogosphere), from the Wall Street Journal or the Washington Post (for the more temperate Right Blogosphere), or from talk radio (for the more outrageous Right Blogosphere).

Didn’t anybody ever read the Village Voice or Mother Jones years ago? Or listen to talk radio? I seem to recall a pretty harsh tone there that predates the Internet/blogosphere by decades.

I think that what John is seeing is just a generational shift.

Well I think it’s pretty clear that Al Gore invented the Internet with the specific purpose of subverting civil society.

Yawn. A perusal of some of William Hogarth’s 18th century paintings should be able to help disabuse anyone of the belief that this is a recent or even an American phenomenon.

More voices can be heard using the net.

More voices use curse words.

More rants and rages on issues are possible.

More issues to rant about today.

More and faster comments are possible than when using letters to the editor, or word of mouth.

Fewer editors to deal with to get one’s message out.

Fewer strict editors or site owners.

The population is just as coarse today as it was 230 years ago, only a lot larger.

It is a freedom of speech demonstration. What’s not to like?

Edit your site!

Our present day failings in civility are boring and pedestrian compared to the precedent set by earlier generations. Democrats’ abuse of the word “extremist,” constant battles over whether the word “liberal” is an insult or a badge of honour, and tendentious, dreary accusations of “questioning others’ patriotism” can’t hold a candle to the likes of:

Sandwich: “Sir, you will either die on the gallows or of some unspeakable disease.”

Wilkes: “That depends, sir, on whether I embrace your policies or your mistress. ”

Disraeli (on Gladstone’s Cypress Convention): “Which do you believe most likely to enter an insane convention, a body of English gentlemen honoured by the favour of their Sovereign and the confidence of their fellow-subjects, managing your affairs for five years, I hope with prudence, and not altogether without success, or a sophistical rhetorician, inebriated with the exuberance of his own verbosity, and gifted with an egotistical imagination that can at all times command an interminable and inconsistent series of arguments to malign an opponent and to glorify himself?”

Or this little gem Volokh discovered recently:

Hamilton: “This scrutiny [of some of John Adams’s writings] enhanced my esteem in the main for his [Adams’s] moral qualifications, but lessened my respect for his intellectual endowments. I then adopted an opinion, which all my subsequent experience has confirmed, that he is a man of an imagination sublimated and eccentric; propitious neither to the regular display of sound judgment, nor to steady perseverance in a systematic plan of conduct; and I began to perceive what has been since too manifest, that to this defect are added the unfortunate foibles of a vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object.”