Is America Too Genteel?

David Brooks blames our economic woes on a change from a culture that valued productive work to one of gentility. And Bill Cosby.

I don’t know that David Brooks has succeeded in crafting the dumbest column ever published in the NYT, but he has a contender in “The Genteel Nation.” Some snippets will suffice to illustrate.

Most people who lived in the year 1800 were scarcely richer than people who lived in the year 100,000 B.C. Their diets were no better. They were no taller, and they did not live longer.

If by “most people,” he means “most people on planet earth,” he’s right. If he means “most people in Northern Europe,” it’s an absurdity. His larger point, that the Industrial Revolution radically transformed our economic lives as compared to our Stone Age ancestors, is of course right. But there was significant progress in the intervening 101,800 years.

Britain soon dominated the world. But then it declined. Again, the crucial change was in people’s minds. As the historian Correlli Barnett chronicled, the great-great-grandchildren of the empire builders withdrew from commerce, tried to rise above practical knowledge and had more genteel attitudes about how to live.

They also exhausted themselves in a series of world wars, lost their colonial empire, and were surpassed by the continental power that had emerged across the Pond in America. But, oddly, I believe their height and diet continued to be quite good.

If you look at America from this perspective, you do see something akin to the “British disease.” After decades of affluence, the U.S. has drifted away from the hardheaded practical mentality that built the nation’s wealth in the first place.

The shift is evident at all levels of society. First, the elites. America’s brightest minds have been abandoning industry and technical enterprise in favor of more prestigious but less productive fields like law, finance, consulting and nonprofit activism.

It would be embarrassing or at least countercultural for an Ivy League grad to go to Akron and work for a small manufacturing company. By contrast, in 2007, 58 percent of male Harvard graduates and 43 percent of female graduates went into finance and consulting.

Were a lot of Harvard grads working for Akron manufacturies half a century ago? In any case, it would be foolish for them to go there now, what with all the manufacturing being in China, Bangladesh, and other places with drastically more profitable labor conditions. Thankfully, our brightest minds instead built a whole new — and radically more productive — set of industries in high tech, biomedical, and, yes, finance. The last of these, alas, is having some difficulty at the moment.

The shift away from commercial values has been expressed well by Michelle Obama in a series of speeches. “Don’t go into corporate America,” she told a group of women in Ohio. “You know, become teachers. Work for the community. Be social workers. Be a nurse. … Make that choice, as we did, to move out of the money-making industry into the helping industry.” As talented people adopt those priorities, America may become more humane, but it will be less prosperous.

I’m guessing that very few of our geniuses will go into nursing, social work, or elementary education. Some will go into higher education, as they always have, and some will go into think tanks, lobbying, and other “prestigious but less productive” fields. Hell, some will go on to be newspaper columnists, quite possibly the least productive field of them all. People drawn to these endeavors likely weren’t going to go out and invent the Next Great Thing, anyway. But I’m not seeing any indication that we’re not continuing to draw large numbers of talented people to the high tech sector.

Then there’s the middle class. The emergence of a service economy created a large population of junior and midlevel office workers. These white-collar workers absorbed their lifestyle standards from the Huxtable family of “The Cosby Show,” not the Kramden family of “The Honeymooners.” As these information workers tried to build lifestyles that fit their station, consumption and debt levels soared. The trade deficit exploded. The economy adjusted to meet their demand — underinvesting in manufacturing and tradable goods and overinvesting in retail and housing.

Ralph Kramden was a morbidly obese transit driver two steps above poverty; he never represented the middle class ideal nor, certainly, would we want him as its exemplar. The Huxtables were a pediatrician and an attorney, at least second generation college, lovingly raising their five children; they’re actually much better role models albeit for an upper middle class or upper class lifestyle.

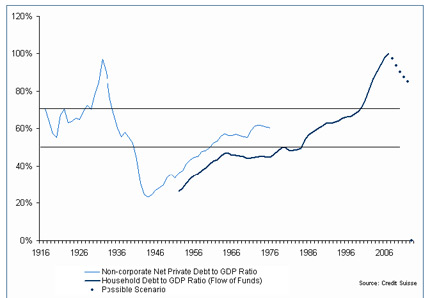

Brooks is right that household debt has soared, and I agree that part of it is that too many Americans are living beyond their means, thinking themselves entitled to a lifestyle they haven’t earned. Here’s a chart showing the Household Debt to GDP ratio over the past several decades:

Is it Bill Cosby’s fault? Well, the upward trend did start around the time his show debuted in 1984. But I’d guess that larger economic trends had something to do with it as well.

These office workers did not want their children regressing back to the working class, so you saw an explosion of communications majors and a shortage of high-skill technical workers. One of the perversities of this recession is that as the unemployment rate has risen, the job vacancy rate has risen, too. Manufacturing firms can’t find skilled machinists. Narayana Kocherlakota of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank calculates that if we had a normal match between the skills workers possess and the skills employers require, then the unemployment rate would be 6.5 percent, not 9.6 percent.

There are several factors contributing to this mismatch (people are finding it hard to sell their homes and move to new opportunities), but one problem is that we have too many mortgage brokers and not enough mechanics.

This is lamentable only in hindsight. It’s perfectly natural that mechanics and machinists wanted a better life for their children, so they worked hard to be able to send them off to college. The perverse consequence of this is that we had a glut of people with college degrees and drove up the salaries of mechanics and machinists. But the answer here is to change our “every child must go to college or he’s a failure” mentality, not an aspiration to keep children of the laboring classes in their place.

Finally, there’s the lower class. The problem here is social breakdown. Something like a quarter to a third of American children are living with one or no parents, in chaotic neighborhoods with failing schools. A gigantic slice of America’s human capital is vastly underused, and it has been that way for a generation.

Didn’t these people watch “The Cosby Show”? Snark aside, this is obviously a huge problem. But what to do about it?

We can get distracted by short-term stimulus debates, but those are irrelevant by now. The real issues are whether the United States is content with gentility shift and whether there is anything that can be done about it in any case.

But, somehow, I don’t think “gentility” is what’s created the underclass. Nor are we going to revert to the robust manufacturing economy with little external competition that prevailed for the fifteen or so years after World War II. It’s gone forever.

UPDATE: In a posting at his own digs titled “You Take the Jobs That Are on Offer,” Dave Schuler observes:

We didn’t lose a half million engineering jobs in the United States over the last ten years because of a mental shift. The loss of jobs caused the mental shift. High-paying jobs in science or engineering just weren’t on offer but jobs in finance and law were.

He has some related thoughts on what happened to those engineering jobs.

Yeah, this one caught my eye, too, and I posted on it yesterday. Half of the Harvard graduating class goes into finance because they’re intelligent, driven people who want money. If that’s gentility, it’s changed.

I found your piece via Google Reader probably as you were commenting.

And, yes, good point on the odd definition of “gentility.”

I don’t think manufacturing per se is crucial to a country’s economic well-being. However, I also am inclined to think that a large country such as the US cannot sustain high growth with only finance and law, which is perhaps Brooks’ larger point. Of course, finance and law are important, it’s just a question of whether they are sufficient for a large country. (I am perhaps biased since I am in engineering/science.)

I don’t have any actual evidence to back it up, but there does seem to have been a general shift in US attitudes away from technology, engineering, and science starting since maybe the 1950’s-60’s when interest was at a peak. It may take several generations for the full effects of this shift to be felt, and in part, it has been offset by immigration.

I could start with other things, but I’m pretty sure Brooks has the historical record right. It’s in the bones. Hunter gatherers had higher stature, health, and life expectancy than early farmers. It has led to a serious question of why people settled down. One amusing answer was that it was easier for farmers to brew beer.

That feudal peasants would be coming up short doesn’t surprise me at all.

To continue, isn’t the link I threw yesterday applicable? Fully one third of our university graduates (ages 25-29) are working in unskilled jobs.

http://timiacono.com/index.php/2010/09/10/young-and-overqualified/

Dave is right that people going to highly paid and aggressive jobs aren’t ‘genteel’ in the old British sense, but I wonder how many of those under employed graduates went for ‘genteel’ degrees in our 2010 sense.

If it is a mismatch in education and the market, it should resolve itself, but I worry that it could take a generation.

Dave, the fact that engineering graduates have the highest starting salaries in 2010 means that the graduates are rarer than the positions.

http://www.cnbc.com/id/29408064/Highest_Paid_Bachelor_s_Degrees_2010

Simple supply and demand.

Data on early life expectancy:

http://apps.business.ualberta.ca/rfield/LifeExpectancy.htm

One amusing answer was that it was easier for farmers to brew beer.

There’s nothing amusing about that at all: water was poison in prehistoric times (and still is in many places); brewed and fermented beverages are almost always potable. See ” A History of the World in Six Glasses” by Tom Standage.

More generally, see the work of Matt Ridley,

Interesting.

I’m not sure you understand. FINANCE that is dependent upon credit expansion is NOT PRODUCTION, and in particular, for very complex reasons, not an EXPORT that can rescue a country from recession due to vast reorganization of industries, and foreign wage arbitrage.

He’s simply saying that finance is a safe haven. It externalizes risk. It is not helping us.

And the person above who states ‘The market will clear the problem in a generation’ is correct. But a nation can lose it’s competitive position in a generation.

I wasn’t thinking of that, Kip. I was thinking more degenerate farmers versus noble savages.

My library has “Six Glasses,” I’ll see if I can get it.

The trend towards law and finance over engineering, et al, as careers goes hand in hand with our kindler, gentler, progressive nanny state politics. They all emphasize carving up the pie rather than baking new ones.

Troll much Charles? Gordon Gecko as a big fat liberal?

I also believe Brooks is right about Northern Europe. Most people in 1800 Britain/Europe didn’t live that well.

As people in America have gained affluence, they naturally steered their kids away from the practical arts (trades). The practical arts have historically been looked down upon even as they are essential. “All the useful arts, I believe, we thought degrading.” (Plato). Not to mention, the unfounded reputation that the useful arts were for those without the intelligence for the university.

Couple the reputation problem with the ever present failings of the education majors. Who starting in the mid-1970s have dismantled all “shop” classes in the nations high schools. Without exposure to practical skills, with emphasis on “going to college.” why would a kid go into the useful trades when it is presented as the place for those who just aren’t going to make it. Without the exposure to the manual skills, kids who do show up at the manufacturers door don’t have the basic tool skills taken for granted in the past due to coming off the farm or working with a blue collar parent.

Then throw in the tradesman glut caused by the decline in manufacturing employment. For a kid starting out in the late 1970s to early 1990s, a career in the trades was not an easy option due to all the older workers displaced from the factory floor. Companies didn’t take on apprentice level workers when they could “just in time” hire a skilled older worker. Unions didn’t run large training programs since their current members didn’t want the competition for the declining number of jobs. Now that skilled worker glut is passing, suddenly, crisis. But you can’t get a master or journeyman skilled worker out of a school, practical on-the-job experience is required which takes years to develop. Oh, and it required an investment in the person even after company loyalty has been razed by brilliant Harvard educated managers who only saw their bonus for the quarter instead of a longterrm future for the company. So expect to pay more for that plumber and have crooked houses from that illegal immigrant framer you got on the cheap.

If America is too Genteel, it was caused by a deep and abiding failure to plan for the future by people like Brooks, who used up all the skilled labor while pontificating so as to discourage new blood from entering the pool. Thanks Woodstock generation.

Oh, no doubt. But they lived indoors and had access to agricultural products, iron tools, money as a store of value, and other fairly important innovations.

Brooks would have been on much safer ground using a less expansive but still impressive timeline. There’s doubtless been more innovation in the last 50 years than there was between, say, 1000 AD and 1700 AD.

We’ve also had that incredible focus on “bits not bricks” in the last 30 years. My grandfather was a watchmaker (and early radio builder). My dad was a prototype machinist (and then educator). I was a computer programmer. There’s a little bit of a progression in that. To an extent we followed the tech.

Now people are bending back (‘maker’ movement again) to bricks not bits. I’m not sure it will take a generation. That would be worst case. If we want to get in front of it, we could talk about where kids should go now.

You can get engineering degrees, and I know some junior colleges have machinist programs.

James, he set his bar at 1800. Think about how most people lived then, at the close of the seventeenth century. (I think you are bleeding forward into the middle 19th.)

FWIW, my grandmother grew up shoeless in 1900s Denmark.

He set his beginning as 100,000 BC, deep in the Stone Age. We had nearly a dozen historical eras after that, notably the Bronze Age and the Iron age. We went from roaming the earth foraging for food to enclosed agriculture, working with forged tools, living indoors, rudimentary sewage systems, sovereign states with advanced legal systems, etc.

Yes, there was still rampant poverty in 1800, barely at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. But it wasn’t the Stone Age, either.

James, I gave you a link right? Why the sophistry? Just back off this one.

Or get some data.

More data, a graph showing essentially flat life expectancy until the industrial revolution:

http://filipspagnoli.wordpress.com/stats-on-human-rights/statistics-on-health/statistics-on-life-expectancy/

“The Chart below shows life expectancy increasing linearly starting around 1820, as a result of the Industrial Revolution. ”

http://open.salon.com/blog/jeffrey_dach_md/2009/01/04/future_medicine_nightmare_or_salvation

> The trend towards law and finance over engineering, et al, as careers goes hand in hand with our kindler, gentler, progressive nanny state politics.

It was widely reported yesterday that automobile related deaths are at lowest in 60 years, an interesting collaboration between “the nanny state” and engineers. It is worth noting that the auto industry resisted seat belts, windshield wipers and air bags.

No doubt you pine for those days of rugged American individualisim when you were much more likely to get a phone call telling you someone you love was not coming home.

Right-wing historical analysis:

Charles – it was the government.

JKB – it was the hippies.

Hell, they were slipping into relative decline even before that. It wasn’t just the US that was surpassing them in size (if not yet military power); Imperial Germany was rapidly becoming the dominant industrial and military power in Europe, for example.

I don’t see why the Financial Sector gets a bad rap simply for exploding in size and importance over the years. As the world and American economies both grew enormously in size, and the world economy began to integrate across national lines, it was more or less inevitable that a gigantic financial sector was going to grow up to meet the needs of that economy. And where else should it grow up, than in the places that were already financial centers (London, New York), and thus most primed to take advantage of the growth?

That Financial Sector was going to grow up somewhere, and I’m glad it grew up in the US.

That’s certainly part of it, although we shouldn’t forget the structural incentives that were favoring this trend. Namely, the easy, low-interest money floating around in the US, and a housing bubble that was making tons of people think they could do well off of speculation.

Part of that also comes from the decline in drop-out and high-school-degree only jobs (and skilled labor jobs are not the same thing – many of them require their own specialized training). It put social pressure on the high schools to graduate everybody, and created some of the “credential creep” problems we have.*

It’s interesting to look at some of the estimated per capita income figures from that era. I remember reading an estimate of what your average manservant in London made, and it was significantly less than a dollar a day.

The old economists’ reason for having a financial sector is to assure efficient allocation of capital – allocation to those productive enterprises.

The discussion I’ve heard amongst economists was whether the financial sector had really gone beyond that, and essentially what level of derivatives trading is working toward that efficient allocation.

Has the financial sector grown too big?

Speech by Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB

http://www.ecb.int/press/key/date/2010/html/sp100415.en.html

Brooks missed the real effects of the Genteel class. They want to reorganize the U.S in order to subsidize their standard of living. If you think about what would make life easier for a free-lance writer living in Burling Vermont, then that is what the genteel class is going to support. That is why the elite, white, liberal progressives really wanted sing-payer health care along with open borders, unlimited immigration, and college for everyone.

The genteel class wants the government to subsidize their standard of living while taxing the crap out of anyone who actually make something.

That seems an odd list, but then again, I am not a Vermont writer, so what do I know.

FWIW, I do think a voucher-based public insurance system would be good for US competitiveness and economic dynamics. Heck, the Kaiser figured that out.

John,

The genteel would love to disconnect health care from work because they do not want to work. If they get the same health care whether they work nights, weekends, and holidays as a nurse as the would being a writer in Vermont, they will want the system.

The genteel love unlimited immigration so that immigrants can do all of the blue collar, technical, and health care work so that they, the genteel, can spend all of their time writing, hanging out, putting on plays, and being political activist. The genteel would love to be the patron class of a country filled with non-english speaking, functionally illiterate immigrants or with hard working immigrants who will do all of the productive work.

The genteel would love college for everyone to include graduate school because it would create more academic jobs for the genteel.

I’m retired, and don’t want to start working again, because “normal” insurance rates climb to the moon, it’s true. I can handle the cost structure now, but I’m not totally comfortable with what we’ll face 10 or 20 years from now, with the healthcare inflation curve looking the way it does.

But, I also know that the insurance picture distorts job-hopping and entrepreneurship among young parents. Never so much in history have people held onto non-ideal jobs for the health insurance.