John Cochrane on the Financial Crisis

University of Chicago Professor John Cochrane explains the causes of the financial panic and how two mistakes turned what might have been a mild recession into a deep recession.

The short form is:

- Failure to bailout Lehman Brothers after bailing out (or at least appearing to) Bear Stearns.

- The chaos surrounding the TARP legislation.

Cochrane points out that the bankruptcy of Lehman was nothing special in an of itself. Many of Lehman’s operations were back up and running within days under new owners. Overall, it was unremarkable save for a few glitches here and there. What was really problematic though was that initially the government had signalled that it would bailout large financial entities under the “too big to fail” belief. Then when Lehman indicated it was in trouble the government not only didn’t act, it claimed it didn’t have the legal authority to act. Basically the belief that the government saw large financial entities were “too big to fail” was in serious doubt and people panicked.

After that the TARP mess just made things worse. As Cochrane puts it,

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson, and President Bush got on television and said, basically, “The financial system is about to collapse. We are in danger of an economic calamity worse than the Great Depression. We need $700 billion, and we won’t tell you what we’re going to do with it. If you need a hint, we justmade it illegal to shortsell bank stocks.”

These speeches should be remembered as a case study in how to start a financial crisis, not how to relieve one. In the Washington context theymay havemade sense, and I understand and sympathize with the awful position that Bernanke and Paulson were in. I suspect that they wanted legal authority to bail out the likes of Lehman and they needed to scare Congress into giving themthemoney, even as stubborn rightwing fiscal conservatives like Barney Frank were saying impolite

things like, “No one in a democracy, unelected, should have $700 billion to spend as he sees fit.” Alas, the speeches scared everyone outside the Beltway too.

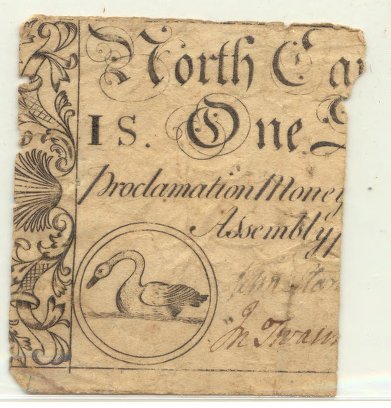

And these kinds of things did not start recently. As has been noted before this has happened before. In 1998 the government bailed out Long-Term Capital to some financial fall out. You can read about it here, but the bottom line was that a bail out was arranged because fairly large amounts of money were owed to Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, and Lehman Brothers.

Cochrane’s look at mortgage backed securities and how things went so wrong there is interesting as well.

Third, it hides risk and avoids regulations, which may be much of its design. An institution that issues short-term debt to hold mortgages is what we used to call a “bank.” Why call it an spv? Because the regulations assessed lower capital requirements on spvs. This structure allows investors who really do want higher risks and higher yields, but are constrained by regulations that specify types (commercial paper) and ratings of individual securities they must hold rather than focusing on portfolio risk. Thus the regulatory system ends up encouraging artificial obscurity and fragility.

It is often claimed that “free, deregulated markets failed,” bringing about the housing collapse and financial crisis. In fact, the free, relatively deregulated equities market absorbed massive losses this time, as last time, with relatively little turmoil. It was the regulated, supervised part of themarket that failed.

I recommend reading the whole thing.

Huh?

In Latin:

toungus cheakus implantus

At least this is better than John Cochrane’s moronic idea last month that bond markets crashed because of a speech from President Bush.

I don’t get the argument about mortgage backed securities.

So, regulation is to blame because efforts to avoid regulation went awry?

Isn’t that sort of like arguing that crime occurs because the government makes stuff illegal? I mean, if there were no laws against theft, criminals wouldn’t steal or something? True in a tautological sense, but sort of besides the point.

With no regulation, the locus of the problem may have been different, but not the problem itself.

Maybe this is just a definitional problem, but turmoil in the equity markets looks a lot different than turmoil in debt markets. In debt markets, turmoil looks like default. In equity markets, it looks like no one investing in new deals. Guess what happened (and is largely still happening) in equity from late 2007 on? No deals.

What total quackery. Yes, the financial crisis and recession were caused by whether or not Lehman Brothers was bailed out! Um, hello, housing prices were outpacing income gains by a factor of three over several decades! There’s no macroeconomy on earth where that doesn’t end in exponential consumer debt, a default wave and a following massive price decline, which leads to… massive financial losses! And a giant recession! Financial sector bailouts don’t make massive losses go away and corresponding activity collapse go away.

You’re hopeless, Steve, and you make me feel hopeless – that someone relatively civil and intelligent could use their gifts in the service of such a deliberately false and misleading worldview. And congrats on combining constant whining about debt with the endorsement of an op-ed claiming that if we’d just handed over more trillions of taxpayer dollars more quickly, everything would have been fine!

Glasnost,

No, they are what turned a bad situation into really bad situation. Cochrane is not saying there would have been no recession, but that it might have looked more like 2001 than what we have now.Sorry Glasnost, upon thinking further of your comment, I think the best answer is simply: WTFAYTA? Handing over even more of taxpayers dollars…you really think that is my “world view”?

Bernard,

I can tell you don’t understand the argument. It isn’t that regulation is to blame, but bad regulation is to blame. We have a bad regulatory environment, it is complicated and allows for this kind of strategic behavior that has helped give rise to this mess. Cochrane states a page or two later that he thinks risk limiters that are clear and simple would work better.

So it comes down to Volcker vs Warren. I favor Volcker. I think we need to reduce the size of these institutions. Then, we largely deregulate them, leaving some few but very difficult to avoid regs. Then if they fail, we let them fail.

We do have the Canadian example, so it is possible to have large banks that are regulated so that they dont crash the system. However, I think there is too much room for the wealthy to intrude into the regulation process. Break em up, let em fail.

Again, this from Simon Johnson.

“The big four have 1/2 of the market for mortgages and 2/3 of the market for credit cards. Five banks have over 95% of the market for over-the-counter derivatives. Three U.S. banks have over 40% of the global market for stock underwriting.”

Steve

So, to clarify, you support a robust regulatory framework as long as it is “good regulation.”?

Or are you one of those believers in the self-regulation capacity of markets? Sort of a pre-chastened Greenspan position?

“In 1998 the government bailed out Long-Term Capital to some financial fall out.”

This wikipedia page clarifies. The government organized a bailout by private firms. It was not taxpayer money. A crucial difference.

I think we’d all be happier if that pattern and expectation had continued. Then, in response to the Lehman and bank problems, the government might “organize” another bailout by monied players.

The problem this time around was that too many were too big and failing. No one was left to pay, other than the payer of last resort.

In summary, I think LTCM was a lesson but not one about government bailout or moral hazard. Instead, it was a lesson about VAR (value at risk) and how “smart” people can blow up.

If Lehman and the banks had taken THAT lesson we wouldn’t have had securitized liar loans and this broad credit crisis.

See also the AAA ratings scandal.