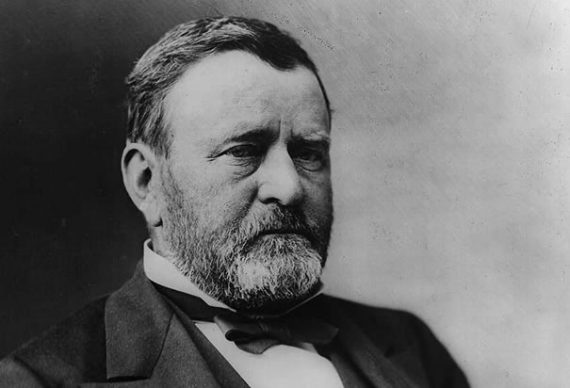

Lessons from a Dying Ulysses S. Grant

The diary entries of a dying Ulysses S. Grant shed some interesting insights into a different time.

William Dale, section chief of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the University of Chicago, takes a look at the diary entries of a dying Ulysses S. Grant and observes, “The insights into palliative medicine are remarkable, especially given the continuing ignorance of them in our own day.” Grant describes the physical toil the head and neck cancer was taking on his body and his attitudes towards his medical care with terse dispatch and humor:

Describing the pain and symptoms he was having, “…I have watched my pains and compared them with those of the past few weeks. I can feel plainly that my system is preparing for dissolution in three ways: one by hemorrhages, one by strangulation, and the third by exhaustion.” This is a stunningly prescient and dispassionately clinical description of his prognosis, and one that I would be proud to hear from any intern on my service.

Then, impressively, he makes his care preferences clear for his doctors:

“I have fallen off in weight and strength very rapidly for the last two weeks. There cannot be a hope of going far beyond this time. All any physician, or any number of them, can do for me now is to make my burden of pain as light as possible.”

A clearer description of the desire for a palliative approach at the end of life couldn’t be clearer.

Next, we worries openly about his current family doctor insisting on bringing in specialists, “I dread them…knowing that it means another desperate effort to save me, and more suffering.”

Much more of that and Dale’s analysis in the post. Perhaps more interestingly, given how bitterly some of my fellow Southerners still hold on to the late unpleasantness with the North, is this:

“It has been an inestimable blessing to me to hear the kind of expressions towards me in person from all parts of the country; from people of all nationalities, of all religions, and of no religion, of Confederate and National troops alike, of soldiers’ organizations, of mechanical, scientific, religious and all other societies…They have brought joy to my heart, if they have not effected a cure.”

Grant was not only the most successful of the Union generals, winning the war in the western theaters before accepting Lee’s surrender in the east, but presided over the worst part of Reconstruction. Yet, only twenty years after war’s end and eight years after he left the White House, former Confederate soldiers were sending him expressions of kindness during his terminal illness, seeing him as a fellow human being and countryman. How representative they were, I can’t say, but it’s remarkable, indeed, considering that resentments linger six score and eight years later.

via Paul Hsieh

I have seen that look more than once. When my brother in-law stopped his treatment for colon cancer he was finally at peace with himself and his fate.

I don’t know how representative Sam Watkins was, but the people he was most resentful of were the politicians of the South that got them into that mess. He also said he always shot at privates, not officers, as “it was them that did the killing.”

I don’t think there were great resentments after the war between the participants. By the 1880s, blue-gray reunions were not uncommon; they helped soldiers make sense of their experience, and forged a path towards reconciliation of whites. Grant’s pallbearers were Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan, who had fought for the Union, and Simon Bolivar Buckner and Joseph Johnston, who had fought for the Confederacy.

I think anyone who has seen someone die from cancer can sympathize on a human level. I have had three, a cousin, an uncle and a close friend. Another observation that I have is that “modern medicine” made the final days for these loved ones worse not better. My uncle’s treatment cost hundreds of thousands of dollars and while it may have increased his quantity of life a little his quality of life was greatly reduced.

Among other things, Grant was a very good writer.

When my father was diagnosed with a brain tumor, they told him he could live 6 months with intensive chemo, or 6 weeks with no treatment. The oncologist actually seemed to be angry when he declined treatment.

I think more and more people realize that going through intensive treatment to extend one’s life a few months at most at the end isn’t really a good deal.

Modern medice *rocks* for young and middle-aged folks, and even some old folks (say, my father, who had surgery for cancer in 1999 and is still kicking at the age of 87). Both of my daughters were born premature: 6 weeks and 4 weeks early, respectively. Not too long ago, our first would have died and quite possibly would have taken my wife with her. All three ladies are, instead, thriving.

It really depends on the specific situation. There was nothing to be done for my grandfather that made any sense. 89 years old with advanced liver cancer. He declined treatment, and I think he made the best choice available to him. He may have died a little earlier than otherwise, but he avoided chemo.

@CSK:

Quoted for Truth. Grant’s memoirs are a terrific read. He wrote them in a suprisingly short period of time, while dying.

@Rob in CT:

I know. One wishes he’d had more time, if only to write more.

I think those Southern soldiers remembered the honor and kindness that Grant showed Lee and his army at Appomattox. That honor and kindness, beyond the lenient terms of surrender, was exemplified by the Union officer who took the formal surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia, Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain:

The Last Salute of the Army of Northern Virginia