Merle Haggard Dead at 79

A country music legend has passed.

The legendary country music artist Merle Haggard has died, aged 79, of pneumonia.

NYT (“Merle Haggard, Country Music’s Outlaw Hero, Dies at 79“):

Merle Haggard, one of the most successful singers in the history of country music, a contrarian populist whose songs about his scuffling early life and his time in prison made him the closest thing that the genre had to a real-life outlaw hero, died at his ranch in Northern California on Wednesday, his 79th birthday.

[…]

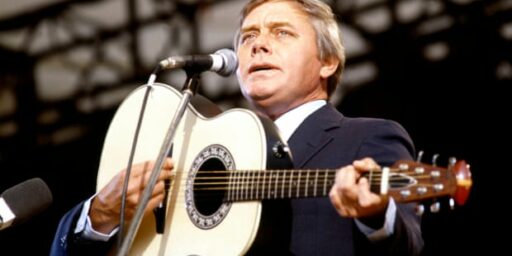

Few country artists have been as popular and widely admired as Mr. Haggard, a ruggedly handsome performer who strode onto a stage, guitar in hand, as a poet of the common man. Thirty-eight of his singles, including “Workin’ Man Blues” and the 1973 recession-era lament “If We Make It Through December,” reached No. 1 on the Billboard country chart from 1966 to 1987. He released 71 Top 10 country hits in all, 34 in a row from 1967 to 1977. Seven of his singles crossed over to the pop charts.

He had an immense influence on other performers — not just other country singers but also ’60s rock bands like the Byrds and the Grateful Dead, as well as acts like Elvis Costello and the Mekons, all of whom recorded Mr. Haggard’s songs. Some 400 artists have released versions of his 1968 hit “Today I Started Loving You Again.”

He was always the outsider. His band was aptly named the Strangers.

Unlike his friend Johnny Cash, Mr. Haggard didn’t merely visit San Quentin State Prison in California to perform for the inmates. Convicted of burglary in 1957, he served nearly three years there and spent his 21st birthday in solitary confinement.

Mr. Haggard went on to write “Mama Tried,” “Branded Man” and several other candid songs about his incarceration, all of them sung in a supple baritone suffused with dignity and regret. Many of his other recordings championed the struggles of the working class from which he rose.

Defying the conventions of the Nashville musical establishment, Mr. Haggard was an architect of the twangy Bakersfield sound, a guitar-driven blend of blues, jazz, pop and honky-tonk that traced its roots to Bakersfield, Calif. In Mr. Haggard’s case the sound defined a body of work as indelibly as that of any country singer since Hank Williams.

The Tennessean (“Merle Haggard leaves behind unparalleled legacy“):

Country music has had its share of brilliant songwriters, unmistakable singers and larger-than-life figures. Merle Haggard — who died Wednesday at age 79 — was all three, and the list doesn’t stop there.

As news of the country legend’s death spread on Wednesday afternoon, his fans, friends and fellow music-makers found ways to express their gratitude. Handwritten messages filled pages of a condolence book left at Haggard’s plaque at the Country Music Hall of Fame, and tributes poured in online, as thousands put his influence and impact into words.

That’s no easy task, as no musician before or since has carved a path quite like Merle Haggard. Below are just a few of the ways the late musician was in a class of his own.

Haggard is widely pointed to (alongside Hank Williams) as country music’s most influential singer-songwriter. He penned many of his 38 No. 1 songs, a staggering feat not just in quantity but evidence of his incredible range. He was a master of barroom anthems and tender ballads alike, from “Mama Tried” and “Today I Started Loving You Again” to “The Bottle Let Me Down” and “Swinging Doors.” Regardless of their form, each was masterfully incisive, emotionally potent and often drawn from Haggard’s experiences.

“Merle reveals everything that we need to know about him in the songs that he writes,” Vince Gill said as Haggard received the Kennedy Center Honor in 2010. “His writing is not glamorous, it’s just real. Hag tells it like it is. He is the poet of the common man.”

When Haggard was released from San Quentin State Prison in 1960, “I really never looked back,” he told The Tennessean in 2012. “And I didn’t stumble. I was able to keep my life straight.” Still, when it came to his career, he made his own rules. Few breaks were bigger in the 1960s than an appearance on TV’s “Ed Sullivan Show” — an opportunity Haggard walked out on when he disagreed with a few production choices.

He kept a healthy distance from Music Row both artistically and geographically, maintaining a base in California. It was inevitable that an artist such as Haggard would be absorbed into country’s “Outlaw Movement” alongside Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, but he carved a singular path through his songs. In 2000 he turned heads when he signed with Anti- Records, an offshoot of punk rock label Epitaph.

As he once sang, among “Cowboys and outlaws, right guys and southpaws. … I stand right here where I’m at / ’cause I wear my own kind of hat.”

USA Today (“Merle Haggard left rich country legacy“):

In his 1968 song Mama Tried, Merle Haggard sang of turning 21 in prison. Haggard, who died Wednesday in California on his 79th birthday, had done just that, though not, as he sang in the song, “doing life without parole.”

Haggard’s youth of petty crime, financial insecurity and freight-car hopping eventually informed songs that spoke plainly but not predictably of social outcasts, blue-collar concerns and persistent restlessness.

Aside, perhaps, from Hank Williams, no other figure in country music affected the way songs would be written and how they would be sung as much as Haggard did. A 53-year recording career yielded 38 No. 1 country hits, a run exceeded only by Conway Twitty and George Strait.

Haggard was born in Oildale, Calif., in 1937, the son of a pair of Dust Bowl refugees from Oklahoma. He spent his early years living in a house that his father, James Haggard, had fashioned from an abandoned refrigerated train car.

The elder Haggard died when Merle was 9, throwing his world into chaos. Two years later, he hopped his first railroad car, starting a series of encounters with police that culminated in a stretch of hard time.

Having botched a burglary — he and a friend tried to break into a restaurant while it was still open — Haggard spent two and a half years at San Quentin State Prison before being paroled in 1960, at 23. In 1972, then-California governor Ronald Reagan granted him a full pardon.

Haggard had dabbled in music before prison. Inspired by a Johnny Cash concert at San Quentin, he pursued it in earnest upon his release, eventually landing a gig playing bass for California country star Wynn Stewart.

[…]

Haggard’s most famous hit, Okie From Muskogee, came in the fall of 1969. It spent four weeks atop the country chart; the following year, both Nashville’s Country Music Association and the Los Angeles-based Academy of Country Music picked it as the genre’s top single.

Okie touted traditional, patriotic values in his music. “We don’t burn our draft cards down on Main Street,” Haggard sang on country radio stations as hundreds of thousands gathered for National Moratorium demonstrations against the Vietnam War, “but we like living right and being free.”

But Haggard’s own perspectives, even when it came to that song, rarely were so cut and dried. At times, he seemed to defend its conservative vantage point. Other times, he said he’d tried to put himself in the shoes of people like his father and imagine how they might have felt about the ’60s cultural climate.

Haggard’s politically oriented songs ran the gamut. If there was some question whether Haggard’s personal opinions matched those in Okie, no one could misunderstand his message for a certain type of protester in his next single: “When you’re runnin’ down our country, man, you’re walkin’ on the fightin’ side of me.”

Those songs — and Workin’ Man Blues, where he sang, “I ain’t never been on welfare, that’s one place I won’t be” — made him a favorite of Republicans, to the point that President Nixon invited Haggard and The Strangers to perform at the White House in 1973.

But Haggard answered to his own whims and beliefs, not those of any audience, and he felt no more comfortable in the Nixon camp than he did in Nashville. He sang about interracial romance (Irma Jackson) and illegal immigrants (The Immigrant) with the same kind of empathy he felt for inmates and ramblers.

Later, he criticized the media’s coverage of the war in Iraq in 2003’s That’s the News and the war itself in Rebuild America First. In 2007, he wrote a song supporting Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy.

Most country radio stations didn’t touch those songs. Of course, they hadn’t played many of Haggard’s new records since Reagan had left office.

Rolling Stone (“Merle Haggard, Country Legend, Dead at 79“):

Merle Haggard, who over six decades composed and performed one of the greatest repertoires in country music, capturing the American condition with his stories of the poor, the lost, the working class, heartbroken and hard-living, died at his home in the San Joaquin Valley, California, after a battle with pneumonia, his spokeswoman Tresa Redburn confirmed. He was 79.

In American and country music, few artists loomed larger. Haggard’s career spanned 38 Number One country hits, and his rough hard-edged style influenced country and rock & roll artists from Waylon Jennings and Gram Parsons to Jamey Johnson and Eric Church. As a songwriter, Willie Nelson called him “one of the best.”

“Merle Haggard has always been as deep as deep gets,” Bob Dylan told Rolling Stone in 2009. “Totally himself. Herculean. Even too big for Mount Rushmore. No superficiality about him whatsoever. He definitely transcends the country genre. If Merle had been around Sun Studio in Memphis in the Fifties, Sam Phillips would have turned him into a rock & roll star, one of the best.”

Haggard didn’t have to look far for material. His greatest songs – the Depression-era poverty described in “Hungry Eyes,” the prison diaries “Sing Me Back Home” and “Mama Tried,” the hard-living anthems like “I Think I’ll Just Stay Here and Drink” and “Back to the Barrooms” – were all taken from the pages of his own life. He was born April 6th, 1937 near Bakersfield, California, two years after his family moved west from Oklahoma during the great dust bowl migration. Haggard’s father found work on the railroad, playing fiddle in roadhouse bands on the side, and bought the family a $500 boxcar house. When Haggard was nine, he lost his father to a stroke, setting him on a path of what he called “illegal motion.” A year later, he hopped his first train with a friend, riding for 18 hours until getting caught. “I tried to explain [to my mother] that anybody could ride with a pass; it took a man to ride the way we had,” he said.

At 11, Haggard’s mother turned him into authorities for being “incorrigible.” He spent his teens in an out of reform schools. By his own estimate, Haggard was locked up more than a dozen times, on charges including robbery, truancy, petty larceny, shoplifting, check forgery and car theft.

He credited music as his salvation: At 14, Haggard went to see country star Lefty Frizzell perform in Bakersfield. He snuck backstage and sang one of Frizzell’s songs for the performer, who pulled Haggard onstage. Haggard cited that encounter as the moment he fell in love with performing.

Haggard’s luck ran out in 1957, when Haggard and a friend attempted to rob a cafe. He was sentenced to five years in San Quentin State Prison. He worked in the textile mill and “started trying to build up a long line of good things to be proud of.” The stay shaped the rest of Haggard’s life and music; a conversation with convicted rapist Caryl Chessman through the prison air-vents inspired his death row ballad “Sing Me Back Home;” he chronicled his father’s death and the regret he felt behind bars in “Mama Tried.”

In 1958, Johnny Cash visited San Quentin. Haggard, then 20, was in the audience. “He had the right attitude. He chewed gum, looked arrogant and flipped the bird to the guards—he did everything the prisoners wanted to do. He was a mean mother from the South who was there because he loved us. When he walked away, everyone in that place had become a Johnny Cash fan.” In San Quentin, Haggard said he “saw the light. I realized what a mess I made out of my life, and I got out of there and stayed out of there. Never did go back.”

Truly a remarkable journey. Below are clips of some of my favorite Haggard songs.

A piece of Americana is gone.

A pioneer and a legend.

RIP, sir.

A true working man’s singer if there ever was.

Why is it that law-and-order Republicans love them some “outlaw hero” crooks who sing, but not others?

Oh, right. Duh.