Muhammed Ali Dead At 74

The Greatest Of All Time.

Muhammed Ali, who seemingly arrogantly proclaimed himself ‘the Greatest Of All Time,’ at a young age and then went on to prove it as a boxing legend, a celebrity, and a humanitarian, has died at the age of 74:

Muhammad Ali, the three-time world heavyweight boxing champion who helped define his turbulent times as the most charismatic and controversial sports figure of the 20th century, died on Friday in a Phoenix-area hospital. He was 74.

His death was confirmed by Bob Gunnell, a family spokesman.

Ali was the most thrilling if not the best heavyweight ever, carrying into the ring a physically lyrical, unorthodox boxing style that fused speed, agility and power more seamlessly than that of any fighter before him.

But he was more than the sum of his athletic gifts. An agile mind, a buoyant personality, a brash self-confidence and an evolving set of personal convictions fostered a magnetism that the ring alone could not contain. He entertained as much with his mouth as with his fists, narrating his life with a patter of inventive doggerel. (“Me! Wheeeeee!”)

Ali was as polarizing a superstar as the sports world has ever produced — both admired and vilified in the 1960s and ’70s for his religious, political and social stances. His refusal to be drafted during the Vietnam War, his rejection of racial integration at the height of the civil rights movement, his conversion from Christianity to Islam and the changing of his “slave” name,Cassius Clay, to one bestowed by the separatist black sect he joined, the Lost-Found Nation of Islam, were perceived as serious threats by the conservative establishment and noble acts of defiance by the liberal opposition.

Loved or hated, he remained for 50 years one of the most recognizable people on the planet.

In later life Ali became something of a secular saint, a legend in soft focus. He was respected for having sacrificed more than three years of his boxing prime and untold millions of dollars for his antiwar principles after being banished from the ring; he was extolled for his un-self-conscious gallantry in the face of incurable illness, and he was beloved for his accommodating sweetness in public.

In 1996, he was trembling and nearly mute as he lit the Olympic caldron in Atlanta.

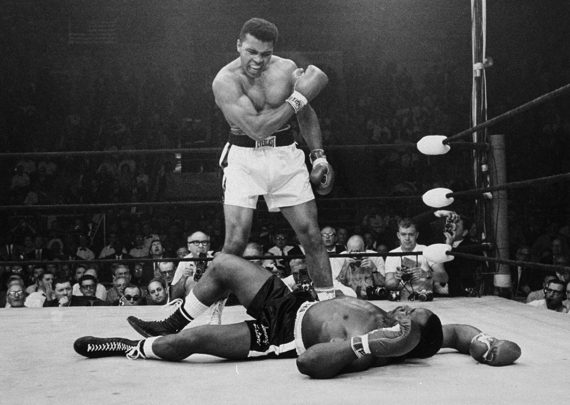

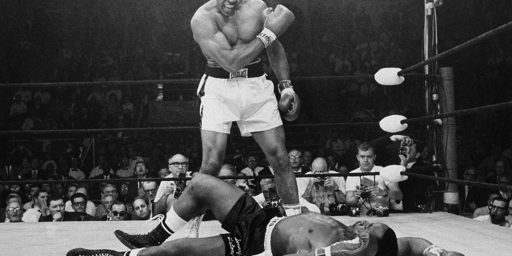

That passive image was far removed from the exuberant, talkative, vainglorious 22-year-old who bounded out of Louisville, Ky., and onto the world stage in 1964 with an upset victory over Sonny Liston to become the world champion. The press called him the Louisville Lip. He called himself the Greatest.

Ali also proved to be a shape-shifter — a public figure who kept reinventing his persona.

As a bubbly teenage gold medalist at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, he parroted America’s Cold War line, lecturing a Soviet reporter about the superiority of the United States. But he became a critic of his country and a government target in 1966 with his declaration “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.”

“He lived a lot of lives for a lot of people,” said the comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory. “He was able to tell white folks for us to go to hell.”

But Ali had his hypocrisies, or at least inconsistencies. How could he consider himself a “race man” yet mock the skin color, hair and features of other African-Americans, most notably Joe Frazier, his rival and opponent in three classic matches? Ali called him “the gorilla,” and long afterward Frazier continued to express hurt and bitterness.

If there was a supertitle to Ali’s operatic life, it was this: “I don’t have to be who you want me to be; I’m free to be who I want.” He made that statement the morning after he won his first heavyweight title. It informed every aspect of his life, including the way he boxed.

The traditionalist fight crowd was appalled by his style; he kept his hands too low, the critics said, and instead of allowing punches to “slip” past his head by bobbing and weaving, he leaned back from them.

Eventually his approach prevailed. Over 21 years, he won 56 fights and lost five. His Ali Shuffle may have been pure showboating, but the “rope-a-dope” — in which he rested on the ring’s ropes and let an opponent punch himself out — was the stratagem that won the Rumble in the Jungle against George Foreman in 1974, the fight in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in which he regained his title.

(…)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. was born in Louisville on Jan. 17, 1942, into a family of strivers that included teachers, musicians and craftsmen. Some of them traced their ancestry to Henry Clay, the 19th-century representative, senator and secretary of state, and his cousin Cassius Marcellus Clay, a noted abolitionist.

Ali’s mother, Odessa, was a cook and a house cleaner, his father a sign painter and a church muralist who blamed discrimination for his failure to become a recognized artist. Violent and often drunk, Clay Sr. filled the heads of Cassius and his younger brother, Rudolph (later Rahman Ali), with the teachings of the 20th-century black separatist Marcus Garvey and a refrain that would become Ali’s — “I am the greatest.”

Beyond his father’s teachings, Ali traced his racial and political identity to the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a black 14-year-old from Chicago who was believed to have flirted with a white woman on a visit to Mississippi. Clay was about the same age as Till, and the photographs of the brutalized dead youth haunted him, he said.

Cassius started to box at 12, after his new $60 red Schwinn bicycle was stolen off a downtown street. He reported the theft to Joe Martin, a police officer who ran a boxing gym. When Cassius boasted what he would do to the thief when he caught him, Martin suggested that he first learn how to punch properly.

Cassius was quick, dedicated and gifted at publicizing a youth boxing show, “Tomorrow’s Champions,” on local television. He was soon its star.

For all his ambition and willingness to work hard, education — public and segregated — eluded him. The only subjects in which he received satisfactory grades were art and gym, his high school reported years later. Already an amateur boxing champion, he graduated 376th in a class of 391. He was never taught to read properly; years later he confided that he had never read a book, neither the ones on which he collaborated nor even the Quran, although he said he had reread certain passages dozens of times. He memorized his poems and speeches, laboriously printing them out over and over.

In boxing he found boundaries, discipline and stable guidance. Martin, who was white, trained him for six years, although historical revisionism later gave more credit to Fred Stoner, a black trainer in the Smoketown neighborhood. It was Martin who persuaded Clay to “gamble your life” and go to Rome with the 1960 Olympic team despite his almost pathological fear of flying.

Clay won the Olympic light-heavyweight title and came home a professional contender. In Rome, Clay was everything the sports diplomats could have hoped for — a handsome, charismatic and black glad-hander. When a Russian reporter asked him about racial prejudice, Clay ordered him to “tell your readers we got qualified people working on that, and I’m not worried about the outcome.”

“To me, the U.S.A. is still the best country in the world, counting yours,” he added. “It may be hard to get something to eat sometimes, but anyhow I ain’t fighting alligators and living in a mud hut.”

Ali would later cringe at that quotation, especially when journalists harked back to it as proof that a merry man-child had been misguided into becoming a hateful militant.

Clay turned professional by signing a six-year contract with 11 local white millionaires. (“They got the complexions and connections to give me good directions,” he said.) The so-called Louisville Sponsoring Group supported him while he was groomed by Angelo Dundee, a top trainer, in Miami.

(…)

Clay enjoyed early success against prudently chosen opponents. His outrageous predictions, usually in rhyme — “This is no jive, Cooper will go in five” — put off many older sportswriters, especially since most of the predictions came true. (The Englishman Henry Cooper did go down in the fifth round at Wembley Stadium in 1963, after he had staggered Clay in the fourth.) The reporters’ beau ideal of a boxer was the laconic Joe Louis. But they still wrote about Clay. Younger sportswriters, raised in an age of Andy Warhol, happenings and the “put on,” were delighted by the hype and by Clay’s friendly accessibility.

In 1963, at 21, after only 15 professional fights, he was on the cover of Time magazine. The winking quality of the prose — “Cassius Clay is Hercules, struggling through the twelve labors. He is Jason, chasing the Golden Fleece” — reinforced the assumption that he was just another boxer being sacrificed to the box office’s lust for fresh meat. It was feared he would be seriously injured by the baleful slugger Liston, a 7-to-1 betting favorite to retain his title in Miami Beach, Fla., on Feb. 25, 1964.

But Clay was joyously comic. Encouraged by his assistant trainer and “spiritual adviser,” Drew Brown, known as Bundini, Clay mocked Liston as the “big ugly bear” and chanted a battle cry: “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, rumble, young man, rumble.”

The Beatles, on their first American tour, were in town and showed up for a photo op at Clay’s training gym. Malcolm X, a leading minister for the Nation of Islam and a worrisome presence to many white Americans, was there, too, with his family members as guests of Clay, whom they saw as a big brother.

To the shock of the crowd, Clay, taller and broader than Liston at 6 feet 3 inches and 210 pounds and much faster, took immediate control of the fight. He danced away from Liston’s vaunted left hook and peppered his face with jabs, opening a cut over his left eye. Clay was in trouble only once. Just before the start of the fifth round, his eyes began to sting. It was liniment, but he suspected poison. Dundee had to push him into the ring. Two rounds later, Liston, slumped on his stool, his left arm hanging uselessly, gave up. He had torn muscles swinging at Clay in vain.

Clay, the new champion, capered along the ring apron, shouting at the press: “Eat your words! I shook up the world! I’m king of the world!”

It was at that point that Ali entered the most controversial, and likely the most difficult, era of his long career:

On Feb. 17, 1966, a day already roiled by the Senate’s televised hearings on the war in Vietnam, Ali learned that he had been reclassified 1A by his Louisville selective service board. He had originally been disqualified by a substandard score on a mental aptitude test. But a subsequent lowering of criteria made him eligible to go to war. The timing, however, was suspicious to some; the contract with the Louisville millionaires had run out, and Nation members were taking over as Ali’s managers and promoters.

“Why me?” Ali said when reporters swarmed around his rented Miami cottage to ask about his new draft status. “I buy a lot of bullets, at least three jet bombers a year, and pay the salary of 50,000 fighting men with the money they take from me after my fights.”

But as the reporters continued to press him with questions about the war, the geography of Asia and his thoughts about killing Vietcong, he snapped, “I ain’t got nothing against them Vietcong.”

The remark was front-page news around the world. In America, the news media’s response was mostly unfavorable, if not hostile. The sports columnist Red Smith of The New York Herald Tribune wrote, “Squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up, Cassius makes himself as sorry a spectacle as those unwashed punks who picket and demonstrate against the war.”

Most of the press refused to refer to Ali by his new name. When two black contenders, Floyd Patterson and Ernie Terrell, insisted on calling him Cassius Clay, Ali taunted them in the ring as he delivered savage beatings.

On April 28, 1967, Ali refused to be drafted and requested conscientious-objector status. He was immediately stripped of his title by boxing commissions around the country. Several months later he was convicted of draft evasion, a verdict he appealed. He did not fight again until he was almost 29, losing three and a half years of his athletic prime.

They were years of personal and intellectual growth, however, as Ali supported himself on the college lecture circuit, offering medleys of Muslim dogma and boxing verse. In the question-and-answer sessions that followed, Ali was forced to explain his religion, his Vietnam stand and his opposition (unpopular on most campuses) to marijuana and interracial dating. Now the “onliest boxer in history that people asked questions like a senator” developed coherent answers.

During his exile from the ring, Ali starred in a short-lived Broadway musical, “Big Time Buck White,” one of several commercial ventures. There was a fast-food chain called Champburger and a mock movie fight with the popular former champion Rocky Marciano in which Ali outboxed the slugger until being knocked out himself in the final round. The broadcaster Howard Cosell, one of Ali’s most steadfast supporters in the news media, was responsible for keeping him on television, both as an interview subject and as a commentator on boxing matches.

As Ali’s draft-evasion case made its way to the United States Supreme Court, he returned to the ring on Oct. 26, 1970, through the efforts of black politicians in Atlanta. The fight, which ended with a quick knockout of the white contender Jerry Quarry, was only a tuneup for Ali’s anticipated showdown with Frazier, the new champion. But it was a night of glamour and history as Coretta Scott King, Bill Cosby, Diana Ross, the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Sidney Poitier turned out to honor Ali. The Rev. Ralph Abernathy presented him with the annual Dr. King award, calling him “the March on Washington all in two fists.”

“The Fight,” as the Madison Square Garden bout with Frazier on March 8, 1971, was billed, lived up to expectations as an epic match. With Norman Mailer ringside taking notes for a book and Frank Sinatra shooting pictures for Life magazine, Ali stood toe to toe with Frazier and slugged it out as if determined to prove that he had “heart,” that he could stand up to punishment. Frazier won a 15-round decision. Both men suffered noticeable physical damage.

To Ali’s boosters, the money he had lost standing up for his principles and the beating he had taken from Frazier proved his sincerity. To his critics, the bloody redemption meant he had finally grown up. The Supreme Court also took a positive view. On June 28, 1971, it unanimously reversed a lower court decision and granted Ali his conscientious-objector status.

It’s hard to imagine what Ali’s career might have been like had he not been unjustly denied his career for those four years. Given that it occurred at a time when Ali was at his physical prime, one can only imagine that it would have been quite impressive indeed and that it would have led to some legendary battles. As it was, though, the time in the wilderness is such a part of the Muhammed Ali we all came to know that it’s hard to separate the two. It was during that time, after all, that his public persona seemed to begin the climb to the greatest heights even as he was barred from participating in the sport that made him famous. It led to the growth of his famous love-hate relationship with Howard Cosell. Most importantly, his willingness to stand on his principles even if it meant having his titles stripped from him helped to shape his character, and his reputation for all time to come. While controversial at the time, his refusal to violate his religious beliefs and decision to resist the draft when he was denied conscientious objector status eventually became a part of the legend and a part of the character that helped him become an international superstar beyond the ring.

Notwithstanding the loss of four years, the reversal of Ali’s conviction and his eventual return to the world of boxing also led to some of the most memorable moments of his career. Over the next six years, Ali would step in the ring for some of his most memorable fights, including three against Joe Frazier, with whom he had a long and bitter rivalry. Frazier won the first of their bouts, retaining his World Heavyweight titles in what was the first loss of Ali’s career, but over subsequent years Ali got the better of his rival and won the final two of their three encounters, including the iconic “Thrilla In Manila” in 1978. After his loss to Frazier, Ali stacked up a number of wins against journeyman boxers before taking on another rival of the 70’s, Ken Norton, to whom he lost the title he held in a match in March 1973, only to win it back in a return bout less than six months later. In 1974, Ali mounted one of the most legendary battles of his career, the “Rumble In The Jungle,” in Zaire against George Foreman, which became the subject of the 1990s Academy Award Winning documentary “When We Were Kings” and during which Ali devised his famous “Rope A Dope” strategy that led Foreman to box himself to exhaustion while Ali preserved his energy for a finish that once again let him emerge victorious.

As the late 70s rolled around, though, it became apparent that the old Muhammed Ali was slipping away. The fast footwork in the ring was slower. The fast wit that had made him such a beloved personality seemed to slowly become hidden behind a cloud. And, more importantly, his skills started to slip. He traded a loss and a win with a boxer named Leon Spinks, a boxer he should have been able to beat easily, and then sustained two losses, to Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick, in what would be the final fights of his career, fights that were seemingly staged principally because he needed the money due to the fact that his personal generosity seemed to know no bounds. Indeed, of the five losses that Ali would suffer during his career, three of them came during those final three years of his career over the course of four matches. At that point, it was clear that Ali’s time in the ring was done. At the time, the press and the public would describe Ali as being “punch drunk,” a condition that seemed to affect many boxers with long careers like Ali’s. We know now, of course, that Ali suffered from Parkinson’s Disease and other neurological issues resulting from a lifetime of blows to the head. Slowly, the fast moving champ began to fade away, although in media appearances you could still get glimpses of the smile and the twinkle in the eye that epitomized Ali throughout his career.

The courage and strength that Ali showed over the next thirty years as Parkinson’s slowly took control of his body is as much the part of his legend now as the fancy footwork in the ring that made him famous at his prime. Perhaps his greatest moment outside the ring, though, came in 1996 when it came time to light the Olympic torch:

I can still remember that moment 20 years later, and it still brings chills. Rest well Champ, you deserve it.

See also: The Washington Post’s obituary, and David Remnick’s piece in The New Yorker The Outsized Life Of Muhammed Ali.

Also, here is the full video of the ‘Rumble In The Jungle’ between Ali and George Foreman:

The ‘Thrilla in Manila,’ the last of Ali’s three bouts against Joe Frazier:

And, the fight that started it all, Ali’s defeat of Sonny Liston in 1964:

And their even more decisive rematch a year later:

RIP Champ!

I know people who despised him for refusing to fight and then wept when they saw him light the torch in ’96. My mom is a nurse who tended to him a few times in the 90’s. Described him as a wonderful charming man with a great sense of humor. He liked to ride up and down the elevators just so he could meet people and see their eyes go wide when they realized who he was. There will never be another like him. RIP.

A great sportsman and a true inspiration. “Is that all you got, George?!”

The butterflies and the bees are weeping today.

There really are no words. He was the greatest-not only for his amazing skills in the ring, but also for his career speaking for civil rights, against the Vietnam War, and for religious freedom.

Ali was no plaster saint. He had a cruel streak in him when it came to taunting his opponents. I hated his treatment of the great Joe Frazier. But he transcended that. He made his own path at a time when it was outright dangerous for black men to stand out and be different.

Parkinson’s was his last fight and he fought it hard, long, and with grace.

Rest in Power, champ.

And screw 2016, already. It’s been a hell of a year-and it ain’t half over.

I’m going to go watch some early Ali-when he was that beautiful young man, at the height of his powers. I think that’s how he would most like to be remembered.

When I was a kid, we adored Muhammad Ali. He was unique, utterly in a class by himself. Time eventually took away his talent, his looks, his health, even his voice. But for all that, he was strangely undiminished. If anything, his stature – already vast – grew as the years passed. Because in the long run, his greatness had nothing to do with boxing. It was the things he carried within himself – the courage, intelligence, determination, compassion and spirituality- that made him “The Greatest”

In the world of sports entertainment and so far beyond that he was a giant, a colossus. He was a brilliant boxer, and the story of his life is almost fable, it’s that compelling and legendary. There was no one like him before him, there was no one like him in his lifetime, and it will be a long time before we see his likes again. He was transcendent.

I already miss him.

He also fought Superman, in a surprisingly good comic book by Neal Adams.

I recall an interview Will Smith gave after the movie came out, in which he said this scene was one that Ali insisted be done and was pleased with. Smith said that to Ali this was when and where the fight was won in Zaire. He said that he decided to ditch his escort and see if all these people chanting his name was all about. It was here he realized the scope of their hopes in him, that hopes were all these miserably poor folks had, and that, for him, losing to George was something he could not allow to happen…and he had no idea how to do that. It was at this moment he says he experienced for the first time in his life real fear. The director’s decision to film it in the exact spot, depending entirely on Will’s face to carry the message is a study in the beauty of understatement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GI2u6-Iy_rQ