NSA Mining Data From Top Internet Content Providers

Big Brother is doing more than just checking your phone records.

On top of yesterday’s revelation about National Security Agency efforts to obtain telephone records from Verizon Wireless, and presumably, other telecommunications firms, we learn today that the agency, along with the FBI, has also been engaging in widespread data mining from some of the top content and service providers on the Internet:

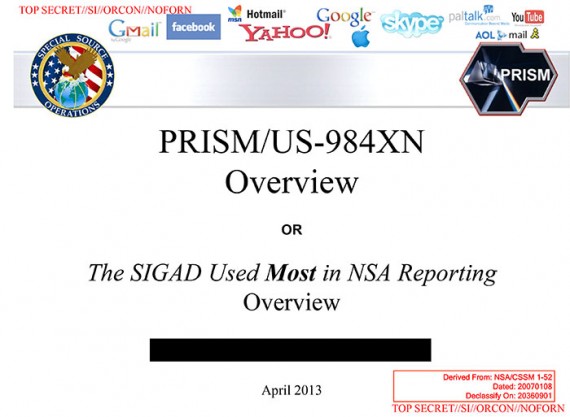

The National Security Agency and the FBI are tapping directly into the central servers of nine leading U.S. Internet companies, extracting audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track foreign targets, according to a top-secret document obtained by The Washington Post.

The program, code-named PRISM, has not been made public until now. It may be the first of its kind. The NSA prides itself on stealing secrets and breaking codes, and it is accustomed to corporate partnerships that help it divert data traffic or sidestep barriers. But there has never been a Google or Facebook before, and it is unlikely that there are richer troves of valuable intelligence than the ones in Silicon Valley.

Equally unusual is the way the NSA extracts what it wants, according to the document: “Collection directly from the servers of these U.S. Service Providers: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube, Apple.”

PRISM was launched from the ashes of President George W. Bush’s secret program of warrantless domestic surveillance in 2007, after news media disclosures, lawsuits and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court forced the president to look for new authority.

Congress obliged with the Protect America Act in 2007 and the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which immunized private companies that cooperated voluntarily with U.S. intelligence collection. PRISM recruited its first partner, Microsoft, and began six years of rapidly growing data collection beneath the surface of a roiling national debate on surveillance and privacy. Late last year, when critics in Congress sought changes in the FISA Amendments Act, the only lawmakers who knew about PRISM were bound by oaths of office to hold their tongues.

The court-approved program is focused on foreign communications traffic, which often flows through U.S. servers even when sent from one overseas location to another. Between 2004 and 2007, Bush administration lawyers persuaded federal FISA judges to issue surveillance orders in a fundamentally new form. Until then the government had to show probable cause that a particular “target” and “facility” were both connected to terrorism or espionage.

In four new orders, which remain classified, the court defined massive data sets as “facilities” and agreed to certify periodically that the government had reasonable procedures in place to minimize collection of “U.S. persons” data without a warrant.

In a statement issue late Thursday, Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper said “information collected under this program is among the most important and valuable foreign intelligence information we collect, and is used to protect our nation from a wide variety of threats. The unauthorized disclosure of information about this important and entirely legal program is reprehensible and risks important protections for the security of Americans.”

Clapper added that there were numerous inaccuracies in reports about PRISM by The Post and the Guardian newspaper, but he did not specify any.

Jameel Jaffer, deputy legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union, said: “I would just push back on the idea that the court has signed off on it, so why worry? This is a court that meets in secret, allows only the government to appear before it, and publishes almost none of its opinions. It has never been an effective check on government.”

Several companies contacted by The Post said they had no knowledge of the program, did not allow direct government access to their servers and asserted that they responded only to targeted requests for information.

“We do not provide any government organization with direct access to Facebook servers,” said Joe Sullivan, chief security officer for Facebook. “When Facebook is asked for data or information about specific individuals, we carefully scrutinize any such request for compliance with all applicable laws, and provide information only to the extent required by law.”

“We have never heard of PRISM,” said Steve Dowling, a spokesman for Apple. “We do not provide any government agency with direct access to our servers, and any government agency requesting customer data must get a court order.”

It is possible that the conflict between the PRISM slides and the company spokesmen is the result of imprecision on the part of the NSA author. In another classified report obtained by The Post, the arrangement is described as allowing “collection managers [to send] content tasking instructions directly to equipment installed at company-controlled locations,” rather than directly to company servers.

Government officials and the document itself made clear that the NSA regarded the identities of its private partners as PRISM’s most sensitive secret, fearing that the companies would withdraw from the program if exposed. “98 percent of PRISM production is based on Yahoo, Google and Microsoft; we need to make sure we don’t harm these sources,” the briefing’s author wrote in his speaker’s notes.

The Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald adds this:

The program facilitates extensive, in-depth surveillance on live communications and stored information. The law allows for the targeting of any customers of participating firms who live outside the US, or those Americans whose communications include people outside the US.

It also opens the possibility of communications made entirely within the US being collected without warrants.

Disclosure of the PRISM program follows a leak to the Guardian on Wednesday of a top-secret court order compelling telecoms provider Verizon to turn over the telephone records of millions of US customers.

The participation of the internet companies in PRISM will add to the debate, ignited by the Verizon revelation, about the scale of surveillance by the intelligence services. Unlike the collection of those call records, this surveillance can include the content of communications and not just the metadata.

(…)

The PRISM program allows the NSA, the world’s largest surveillance organisation, to obtain targeted communications without having to request them from the service providers and without having to obtain individual court orders.

With this program, the NSA is able to reach directly into the servers of the participating companies and obtain both stored communications as well as perform real-time collection on targeted users.

The presentation claims PRISM was introduced to overcome what the NSA regarded as shortcomings of Fisa warrants in tracking suspected foreign terrorists. It noted that the US has a “home-field advantage” due to housing much of the internet’s architecture. But the presentation claimed “Fisa constraints restricted our home-field advantage” because Fisa required individual warrants and confirmations that both the sender and receiver of a communication were outside the US.

“Fisa was broken because it provided privacy protections to people who were not entitled to them,” the presentation claimed. “It took a Fisa court order to collect on foreigners overseas who were communicating with other foreigners overseas simply because the government was collecting off a wire in the United States. There were too many email accounts to be practical to seek Fisas for all.”

The new measures introduced in the FAA redefines “electronic surveillance” to exclude anyone “reasonably believed” to be outside the USA – a technical change which reduces the bar to initiating surveillance.

The act also gives the director of national intelligence and the attorney general power to permit obtaining intelligence information, and indemnifies internet companies against any actions arising as a result of co-operating with authorities’ requests.

In short, where previously the NSA needed individual authorisations, and confirmation that all parties were outside the USA, they now need only reasonable suspicion that one of the parties was outside the country at the time of the records were collected by the NSA.

This program doesn’t appear to be a situation where all of the data that is being shared online is being dumped into a massive NSA database somewhere, but these connections to providers servers that the NSA has allow them to access, presumably at any time and apparently with or without a warrant, internet traffic to see what people that they might be “interested” in. Given the extent to which FISA requirements have been lessened, they now only need to have “reasonable suspicion” that one of the people they are monitoring is outside the country. At the same time, though, this program is clearly far more widespread and ambitious than their near-continuous access to phone call records from Verizon and other teleccom companies. In that case, they are seeking the “metadata” of the calls, the “who, where, and when” of the phone calls to put it in lay terms. In this case, they are going after actual content, and they can apparently access it with easy from the comfort of terminals at NSA headquarters in Fort Meade. At the very least, this is a massive expansion of the ability of the government to monitor the activities of virtually everyone in the country at will, whether or not the law permits them to do it.

As with the cell phone record data mining, it would appear that these practices are completely legal thanks to the changes made to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act over the past decade and, of course, the PATRIOT Act. However, it strikes me that this is really only half of the question. The fact that something is legal doesn’t mean that it’s proper, or consistent with the values enshrined in the Fourth Amendment and other parts of the Constitution. As I noted last night, we’ve given up much in terms of privacy in the nearly twelve years since September 11th, 2001, and the question of whether we’ve gone to far is one that we’ve avoided for far, far too long. The PATRIOT Act passed Congress by overwhelming margins within six weeks after the World Trade Center’s towers fell. In its final form it was more than 1,000 pages long and the actual debate on the bill in both the House and the Senate was quite limited given the broad scope of the powers that were being granted to law enforcement. At the time, we were told that all of this was necessary to keep the nation safe from terrorism and, because the wounds of tragedy were still quite open at the time, most Americans, and most Members of Congress, accepted that reassurance without question. In the years since, the law has come up for reauthorization and we’ve been told that we can’t afford to take back these powers we’ve given the government because of the continued threat of terrorism. In all of this, though, we’ve never really had the kind of wide ranging public debate that these issues deserve.

I don’t doubt that there are some powers that we need to give to law enforcement in order for it to be able to effectively protect the nation. However, there are legitimate questions about how far those powers should go, and how long they should last. The revelations over the past days have shown us how far things have come in just twelve years. At some point, we’ll have to ask ourselves how much further we’re willing to let it go.

1 This is not to say, of course that the ability to have near complete access to phone call metadata is innocuous. In many ways, such information can reveal much more about a person and their activities than the actual content of the phone calls themselves.

“It’s alive! It’s ALIVE!” said the good doctor. Then the monster proceeded to do what monsters do.

“This program doesn’t appear to be a situation where all of the data that is being shared online is being dumped into a massive NSA database somewhere”

When the NSA facility in Utah comes on line it will be.

The news media have lost their minds! It seems to be all about sensationalism! Putting out ALL the facts don’t matter. Let’s just have one hell of a bomb throwing headline. It’s pathetic.

Hands up all those in the audience who know that the founding fathers knew or could envision electronic technology when they founded our nation and how it would be used not only in our country but throughout the world. There, you have your answer and why the information marketplace (there is no longer any news media in our country) is failing our nation every minute of the day.

Ironic that yesterday Doug wrote a post celebrating the rise of the smartphone. IMO, the smartphone is the greatest device ever made for tracking a person’s location, desires and habits. Apple, Google and Microsoft know more about my daily life than the NSA through data mining can ever hope to. They know where I was last weekend, what books I buy, what audiobooks I listen to, what restaurant I ordered take out from this week. And I can’t vote out the heads of those companies.

I don’t have a problem with any of this, because I give it up freely-for convenience.We give up privacy, therefore, for a great deal less than security, so its not surprising that we don’t have trouble giving up privacy for security.

I note that the WSJ supports NSA data mining. A cynic ( like me) thinks this is so because WSJ fears that any crackdown on government data mining will inevitably mean a crackdown on corporate data mining. Oddly, Doug doesn’t seem all that concerned about corporate encroachments on privacy.