Partisanship and Failed SCOTUS Nominees

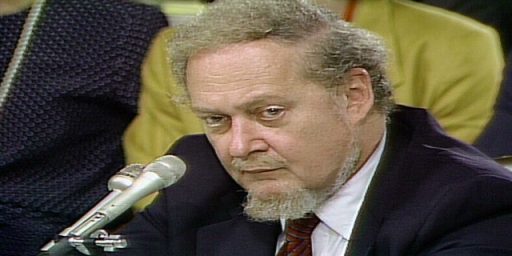

Earlier this morning I noted that since 1976 there have been three failed SCOTUS nominees: Robert Bork, Douglas Ginsburg and Harriet Miers.

Commenter Charles Austin asked “They all seem to have only one relevant thing in common besides being nominated for Justice of the Supreme Court

Commenter Charles Austin asked “They all seem to have only one relevant thing in common besides being nominated for Justice of the Supreme Court . Can you identify it?”

. Can you identify it?”

And yes, it is true that they are all Republicans (or, more accurately, appointed by Republicans). Some further discussion takes place in the comment thread, but I want to bring further the issue to the front page to address a few issues, not to pick on Charles, but because I think that this particular issue is relevant in terms of thinking about our broader politics and the degree to which partisanship is relevant here.

I concur that it is quite clear that the Robert Bork nomination (and defeat) was about ideology. And yes, it has shaped the nomination process since. However, to look at three failed nominees during over a span of roughly 3.5 decades is to allow partisanship to emerge as too large a variable in the analysis.

First, there are some basic probability issues here. To wit: from 1976-2010, the Republicans occupied the White House for 20 years (two terms for Reagan, one for Bush 41, and two for Bush 43) and the Democrats 14 (one for Carter, two for Clinton and half for Obama to date). Beyond that, Carter had 0 picks, Reagan 3, Bush 41, 2, Clinton 2, Bush 43 2 and Obama 1 (the way Kagan goes remains to be seen, so we won’t count that one).

As such:

- Republicans: 7 picks (really 10 total picks, because Reagan had to pick 3 times to replace Justice Powell—Bork, Ginsburg and Kennedy— and Bush 43 had to pick twice — Miers and Alito — to replace O’Connor)

- Democrats: 3 picks

All in all the probabilities that Republicans would have more problems is higher than for Democrats. Conversely, they also have a higher level of success in raw terms.

Again, Bork is unique and has shaped all subsequent picks, and I will readily chalk his rejection up to ideology. His rejection was pivotal and has reshaped the entire nomination process to this day.

Ginsburg smoked pot in college and as a college professor. No Democrat would have survived those allegations in 1987. Indeed, I am not sure that post-college pot smoking wouldn’t kill a nomination today (youthful indiscretions are one thing, but breaking the law as a professional is yet another). Heck, in 1992 then-candidate Bill Clinton had to play the whole “I did not inhale” bit to deflect the marijuana question (i.e., it was seen as politically necessary for him to have only smoked once, and then to have not fully completed the act—and for the record, no, I didn’t believe him then and still don’t. Not, I would note, that I really care).

Given that Miers was attacked from the right and the left, the notion that her Republicanness was determinative is off the mark as well.

Further, of the three examples, only Bork was actually rejected by the process. Both Ginsburg and Miers withdrew.

In short, it is difficult to establish that the most important variable (or even a key variable) is partisanship (save with Bork, but then N=1), if anything because are working with a very small number of cases, and of the three one was clearly not an ideological problem (Ginsburg) and the other was attacked from multiple sides (Miers). In dealing with three cases we don’t have enough information to really establish a pattern.

I really think that this is a situation in which we make a mistake trying to make it into a partisanship issue that proves some bias against Republicans.

I think this is right. And at least two of three (Ginsburg and Miers) genuinely deserved to fail.

If we widen the field a little further, going back to the Nixon administration, we see two more failed picks. Also Republicans. But, in those cases, seemingly picked for the sole purpose of not being confirmed and thus setting the stage for getting a “better” pick through.

Two other factors to consider: Democrats controlled the Congress in every single instance save Miers, so it was naturally harder to get a controversial Republican through. Conversely, the handful of Democratic appointments have mostly come when they also controlled the Congress. That makes a difference.

Additionally, Bill Clinton had many high profile failures: Lani Guinier, Zoe Baird, and Kimba Wood all come readily to mind. They just didn’t happen to be SCOTUS picks.

Yes–I meant to mention the partisan control of the Senate as well, which is a relevant variable as well.

If the Wikipedia list of failed nominees is correct, LBJ had two failed nominees and then one has to go back to Hoover and then to the 19th Century.

Bork’s rejection was primarily ideological, but if all Senate Republicans had voted for him and if he had picked up a few Blue Dog Democrat votes like that of Richard Shelby, he would have been confirmed. The ideological issue was a problem for the center, and not simply partisan.

I also think that since Roe v. Wade, Republicans have set forth on a more ambitious strategy than Democrats in terms of getting young, reliable votes from a profession that is relatively liberal. I see the Democrats as playing more of a prevent defense in their selections.

Regarding Bork,

Do we really need to look beyond the Saturday Night Massacre?

To me, that alone is a dis qualifier for a life long appointment and I’m surprised James didn’t include him in his “genuinely deserved to fail” comment.

I’m not sure what’s going on here. Is there really some attempt to deny that the process is inherently political, and partisan?

Analysis of X many Presidential years for Dems, Y for Repubs? What?? That’s just weird. IMHO James got it right, its about Senate control – power. A tug of war.

All I think charles was attempting to point out was that it is in fact a partisan exercise, and observing that a side that is more powerful at the time, media savvy or willing to go filthy will win.

Further, failure to confirm is not “rare.” Last time I looked 3 out of 11 is about 27%. We can all start parsing who is “qualified,” or “controversial” and attempt to explain away the reasons for failure to confirm, but by its nature those evaluations are in the eye of the beholder. Alternatively, does anyone doubt that foibles that become apparent during the confirmation process haven’t been used to advantage by the opposition, qualifications be damned? (I queried in one thread as to whether having been a judge might not be a reasonable qualification for the highest court in the land and some reacted like I was crazy. Not that that was a partisan reaction, you know.)

I commend SLT on his assertion of being qualification driven, but he is a rare bird. So I think charles’ observation stands, including the willingness of one side to go dirty. Not to be partisan, but in the case of the current nominee somehow I doubt we will be treated to the bizarre spectacle of Senate testimony with references to hairy coke cans and Long Dong Silver.

I concur that it is a political process. I just don’t see that it is actually anti-Republican.

I am not sure why looking at the actual opportunities for success/failure is “weird.” Surely it matters when assessing the situation to see which party had more chances to make appointments.

Indeed, part of my point is that we very much need to take such factors into account if we are going to make a reasonable assessment of the situation.

It should be noted that only 1 was actually rejected, the other two withdrew.

And certainly the general success rate is pretty good.

I think it is all very political and ideological. Although I think it comes more from who is control of the senate than who the white house wants. Bork and later Thomas changed everything. While Thomas was confirmed, his confirmation hearings were quite nasty and quite political.

I think Bush 41’s choice of Souter was an attempt to avoid the nasty hearings of Thomas and earlier Bork.

I think in general Roe v Wade changed everything. I think this is one reason the court make-up is mostly Catholic. I am not sure anyone from an Evangelical religious background would ever be confirmed at this point. The democrats would tear them to pieces on that fact alone, and the WH and GOP wouldn’t want to waste political capital defending them, when they can just look for an acceptable Catholic to appoint.

“I am not sure why looking at the actual opportunities for success/failure is “weird.” Surely it matters when assessing the situation to see which party had more chances to make appointments.”

I await you analysis comparing confirmations to periods of full moons.

“Further, failure to confirm is not “rare.”

It should be noted that only 1 was actually rejected, the other two withdrew.”

Gawd. Dancing on the head of a pin.

See your updated/next post.

@Drew:

Well, if I thought the phases of the moon were relevant I would be happy to include them in the analysis. However, oddly enough, I think the number of opportunities open to Republicans and Democrat to appoint Justices is a relevant issue.

As is rejection by the Senate v. withdrawal. For example, again, it is impossible to assign a partisan motive for the Ginsburg withdrawal.

One wonders if Davebo will be similary impressed:

“Byron York reports on an obscure but potentially embarrassing controversy involving Elena Kagan’s days in the Clinton administration:

In 1995 and 1996, future Supreme Court nominee Elena Kagan was involved in a bizarre controversy in which the Clinton White House was accused of siding with an eco-terrorist group locked in a standoff with federal agents deep in the woods of Oregon. The incident led to an investigation by House Republicans, who concluded that a staffer on the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) tipped off the environmental radicals to impending action by U.S. Forest Service law enforcement agents — a leak that Forest Service officials believed endangered the lives of their agents on the ground.

Kagan, at the time an associate White House counsel, had no role in leaking the feds’ plans to the radicals, but House Committee on Natural Resources investigators concluded she shirked her responsibility by not searching for the source of the leak or pushing for punishment of the leaker.

“Nothing was ever done by Elena Kagan to learn the details about the leaks, or to identify the leaker and ensure that proper punishment occurred,” the committee’s 1999 report concluded. In fact, investigators found evidence suggesting that Kagan, in internal White House discussions, defended the alleged leaker.

(emphasis added) The suspected leaker was a senior CEQ official Dinah Bear who had wide contacts in the environmental community. Bear wrote in an email that “Elena went out of her way to go to bat for yours truly, which was quite decent of her.” When congressional investigators asked the White House for Kagan’s notes of her discussions with Dinah Bear, the White House refused to provide them.”

“Well, if I thought the phases of the moon were relevant I would be happy to include them in the analysis. However, oddly enough, I think the number of opportunities open to Republicans and Democrat to appoint Justices is a relevant issue.”

Well, oddly enough, I suspect the two – to use the analytical tool of the day – are statistically indistinguishable.

“As is rejection by the Senate v. withdrawal. For example, again, it is impossible to assign a partisan motive for the Ginsburg withdrawal.”

Balls. Withdrawal comes when partisans discover red meat, whatever its merits, and which is an amorphous standard.

Anyway. See your most recent post.

Cheers