Radical Center: Friedman’s Fantasy

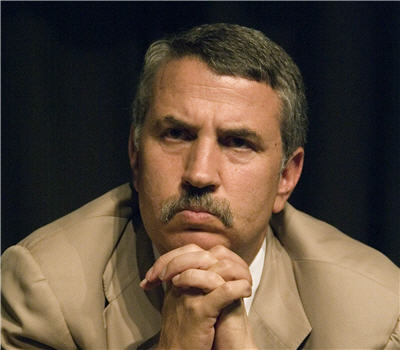

For a really bright fellow who spends a lot of time talking to cabbies and world leaders, Tom Friedman has a remarkably naive view of how the world works. His latest brainstorm is a “Tea Party of the radical center.”

For a really bright fellow who spends a lot of time talking to cabbies and world leaders, Tom Friedman has a remarkably naive view of how the world works. His latest brainstorm is a “Tea Party of the radical center.”

My definition of broken is simple. It is a system in which Republicans will be voted out for doing the right thing (raising taxes when needed) and Democrats will be voted out for doing the right thing (cutting services when needed). When your political system punishes lawmakers for the doing the right things, it is broken. That is why we need political innovation that takes America’s disempowered radical center and enables it to act in proportion to its true size, unconstrained by the two parties, interest groups and orthodoxies that have tied our politics in knots.

The radical center is “radical” in its desire for a radical departure from politics as usual. It advocates: raising taxes to close our budgetary shortfalls, but doing so with a spirit of equity and social justice; guaranteeing that every American is covered by health insurance, but with market reforms to really bring down costs; legally expanding immigration to attract more job-creators to America’s shores; increasing corporate tax credits for research and lowering corporate taxes if companies will move more manufacturing jobs back onshore; investing more in our public schools, while insisting on rising national education standards and greater accountability for teachers, principals and parents; massively investing in clean energy, including nuclear, while allowing more offshore drilling in the transition. You get the idea.

I do!

The problem with this is manifold but, most obviously, as Ramesh Ponnuru points out, “The fundamental reason that politicians haven’t cut entitlements and raised middle-class taxes isn’t the power of hard-core liberals and conservatives. It’s that the public—including most people who could reasonably be described as moderates—doesn’t want them to do these things.”

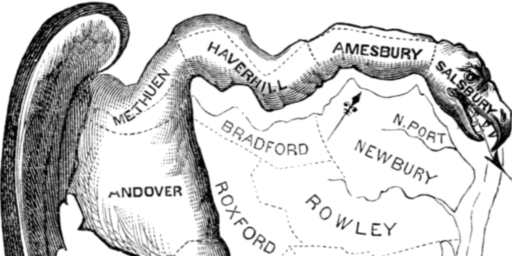

Aside from overreading his own idiosyncratic policy preferences into a majority view — an amusing but forgivable error given how common it is in the pundit class — Friedman fundamentally misunderstands our institutions. He wants to “Break the oligopoly of our two-party system,” despite the fact that two-party systems follow first-past-the-post, single member district setups like night follows day. How?

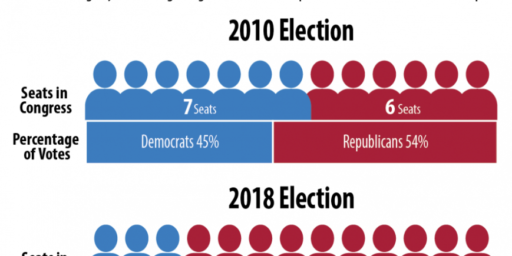

First, let every state emulate California’s recent grass-roots initiative that took away the power to design Congressional districts from the state legislature and put it in the hands of an independent, politically neutral, Citizens Redistricting Commission. It will go to work after the 2010 census and reshape California’s Congressional districts for the 2012 elections. Henceforth, districts in California will not be designed to be automatically Democratic or Republican — so more of them will be competitive, so more candidates will only be electable if they appeal to the center, not just cater to one party.

While perhaps not in the spirit of the Framers, who clearly intended redistricting to be a political process, this is a reasonable enough idea. So much so that at least 12 states — not including California — were doing it in 2000. And several others have advisory committees and other extra-legislative inputs. (See, “The Experiences of Other States — A Comparison of Redistricting Commissions,” PDF.) I’m not sure there’s any evidence that those states are less partisan, much less more prone to tax hikes, benefit cuts, or passing others of Friedman’s pet programs.

Second, get states to adopt “alternative voting.” One reason independent, third-party, centrist candidates can’t get elected is because if, in a three-person race, a Democrat votes for an independent, and the independent loses, the Democrat fears his vote will have actually helped the Republican win, or vice versa. Alternative voting allows you to rank the independent candidate your No. 1 choice, and the Democrat or Republican No. 2. Therefore, if the independent does not win, your vote is immediately transferred to your second choice, say, the Democrat.

Again, I tend to like the idea, which I tend to think of as an “instant run-off” since the effect of “alternative voting” would almost always be to decide very close races, especially those where there’s no majority winner. But let’s not kid ourselves: The impact would be to continue to elect Democrats and Republicans in almost every instance. It’s rare, indeed, that a third party candidate is in second place in the polls going into Election Day.

Regardless of whether we pass these changes — and I see very little groundswell, indeed, for either, especially the second — we’re still going to have a very polarized polity. We’re genuinely divided on major issues of war and peace, freedom and security, and cultural stability vs. tolerance. And we live in a 24/7/365 permanent campaign conducted in a self-selected communications environment.

It’s safe to see that it’s going to take more than a few tweaks — or another six months — to turn us into a nation of Friedmans.

I think there are better stories for The Rise of the Independents than the “radical center” rah-rah that Friedman attempts.

I suspect that shakeout of healthcare etc. will empower the trend, rather than send the disaffected back to the arms of either mainline party.

Aside from overreading his own idiosyncratic policy preferences into a majority view — an amusing but forgivable error given how common it is in the pundit class

That’s Friedman’s MO, to be sure.

And you are correct: his arguments are predicated on rather mistaken interpretations of the way our institutions work and the kinds of outcomes they produce.

Very little groundswell? You did see the polling data running as close on 75/25 as no matter against Obamacare, right?

IRV would actually make third parties even weaker. Right now, pretty much their only influence is through getting a major party to adopt part of their agenda in order to avoid losing elections to protest voters. If those major parties know they’ll get all those protest votes back in the second round, they’re free to completely ignore them.

No I didn’t. Perhaps because I am not privy to the numbers you pull out of your butt. RCP has an average of ~50% against* and the latest poll has a plurality in support.

* The worst this year by any poll shown on RCP is 50% against.

Oops, that should have read 59%. Still a ways short of the 75% coming from bistsy’s imagination.

@GRewGills:

You do read CNN, right?

Translation: 75% say they disapprove of the bill as signed. You really gotta research this a bit better.