Regulatory Capture and the Revolving Door

Top officials of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have taken jobs in the industry they were regulating.

Richard Pollack of the Daily Caller reports on a fairly routine story in Washington circles:

Three of the top four officials at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau have jumped from CFPB to lucrative posts representing financial services industry firms their former agency regulates, according to a Daily Caller News Foundation investigation.

The latest of the departures is Quyen Truong, formerly deputy general counsel, who accepted a position this month with the law firm Stroock & Stroock & Lavan.

Truong’s new law firm represents banks such as Citigroup, Bank of America Merill Lynch, Barclays Capital, Credit Suisse and Deutsch Bank. The company also assists high-flying hedge funds including Carlyle Group, JP Morgan Asset Management and Goldman Sachs, according to its website.

Truong was preceded out the door by her former boss at CFPB, General Counsel Meredith Fuchs, who left in February to join Capital One.

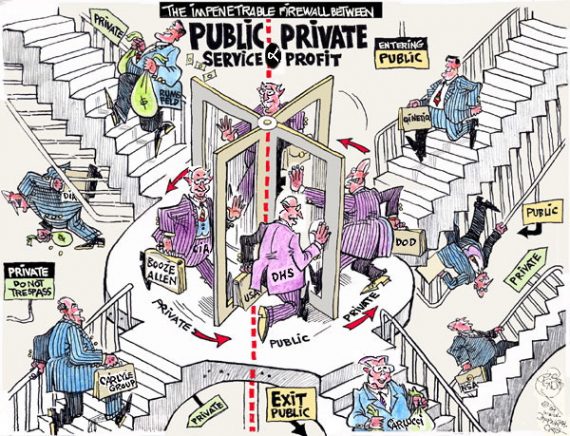

I say “routine” because, as presidential terms wind down, people in appointed positions tend to flee for the private sector to secure more lucrative employment. Some will soon return if their party retains the White House, but they’ll typically expect a promotion. In less cynical times, political scientists termed this the “revolving door.”

Dave Schuler notes the dark side of the practice:

The CFPB was formed in 2010 as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reform bill.

A more cynical man than I might be tempted to think that rather than protecting the interests of consumers the CFPB was created to be yet another venue for placing party apparatchiks in lucrative financial sector jobs.

As Dave notes, the flip side of the revolving door is “regulatory capture,” which Wikipedia defines as, “a form of government failure that occurs when a regulatory agency, created to act in the public interest, instead advances the commercial or political concerns of special interest groups that dominate the industry or sector it is charged with regulating.” Has that happened with the CFPB? It’s hard to tell but the optics are bad.

Let’s take the two examples in the story at hand. Truong served six-and-a-half years in government, including two years as counsel at the FDIC and the remainder at the CFPB. Prior to that, she spend nine years in the private sector with Dow Lohnes PLLC—representing clients with regulatory agencies. That followed three-and-a-half years as associate bureau chief with the FCC. That was preceded by eight years at two different law firms, both doing regulatory-type work.

Fuchs similarly spent a little over six years in government, including four senior posts with the CFPB and 11 months as lawyer for the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Prior to that, she spent thirteen years in various legal positions in the private and education sectors in Washington.

It’s certainly possible to see regulatory capture in those career paths. But the counter-argument is that, when looking to appoint people to various regulatory posts, the president’s team is looking for folks with appropriate experience. Fuchs and Truong were both highly qualified for the posts to which they were appointed. Serving in those high-level government posts, in turn, made them much more valuable upon their return to the private sector. And, of course, serving in enhanced private sector posts could make them more attractive for future government postings.

Absent direct evidence that Fuchs or Truong slanted their regulatory rulings with an eye to their future earning potentials with those they were regulating, there’s no reason to suspect them of wrongdoing. At the same time, it’s easy to see why the public would be cynical of the process. There’s an obvious potential for mischief.

There’s no obvious good solution to this potential for impropriety. Banning public sector employees from doing work that’s even remotely related to their expertise would seriously constrain our ability to hire qualified people. We could, I suppose, shift a large number of currently-appointed positions to the professional civil service, mostly in the Senior Executive Service ranks. But that creates the potential for an entirely different sort of regulatory capture—a bureaucracy that’s completely unresponsive to the wishes of the elected president.

This is a big deal, and there are a thousand examples of this problem. The Forest Service is tied to the lumber industry, and the BLM is full of cattlemen. The Medicare D law requires that Medicare allows Pharma to set drug prices without any bargaining. For years the Department of Agriculture dietary recommendations were totally congruent with the interests of the dairy industry. Our tax code is 70,000 pages of 70,000 loopholes for 70,000 special interests. I’m sure each of you can think of many examples of the problem.

The only possible countervailing force are independent civic minded elected officials, but we have hobbled our chances of getting such paragons. Politics takes enormous amounts of money, and the Citizens United decision allows corporate entities to expend their money to help elect people who serve their interests. Citizens United was a radical empowerment of the hand in glove association of government and industry.

The problem is the alternative ends up being just as bad. Say you’re graduating with a finance degree. You can either go work for a bank, or go work for the CFPB. If you pick the CFPB job, you’re paid less, if you ever get let go you’re completely unemployable, and if your career ever stalls out, you can’t leave for another better job some place else.

Do you think the best and brightest are going to take that job?

So you end up with a CFPB full of lower tier people in the field with no actual experience in how the industry they’re regulating actually works. Not surprisingly, the financial companies end up running rings around them.

So you either end up with a CFPB that effective but way too chummy with the industry or one that’s ineffective and never knows what’s actually going on.

Why doesn’t Congress do something about this?

Oh, yeah, because the CFPB was set up specifically to be exempt from Congressional oversight, and put under the Federal Reserve. Its primary backers — Senator Elizabeth Warren and other key Democrats — wanted to make certain it would be entirely aboveboard and above reproach.

Didn’t Obama promise to shut this revolving door? Wasn’t that one of his key campaign pledges?

@Slugger: You’ve identified several issues, but they’re all examples of something different. Congress writing a law isn’t directly part of this revolving door; indeed, Congress has made it illegal for former Congressmen to lobby for X years after leaving office. Citizens United has nothing to do with regulatory agencies; their employees can’t accept contributions or, indeed, run for office or exercise several normal political rights because of the Hatch Act.

@Stormy Dragon: Quite so. That’s what I was trying to get at with “Banning public sector employees from doing work that’s even remotely related to their expertise would seriously constrain our ability to hire qualified people. ”

@Jenos Idanian: I don’t understand your argument. You can’t simultaneously complain that an agency isn’t subject to political oversight and blame President Obama for poor oversight. The Fed is independent of the political system, at least once installed, although it’s not completely above political considerations.

@James Joyner: The Democrats pushed the bill that created it, and Obama signed off on it. They CHOSE to put it beyond oversight, so they are responsible for it.

It was a bad idea, and they made sure that it couldn’t be fixed when it proved to be a bad idea. So they own it.

The only way I see getting around this is empowering the bureaucracy and turning the politicians into squeaking mice, which is how Japan does its system. Does take a long time to get anything done, and you wouldn’t believe the turf battles between agencies…(rolls eyes). Boy do I have some STORIES.

Well, it makes little difference. Between the Chinese and our underfunding of science and technology, we’re screwed.

@Jenos Idanian:

Putting in under Federal Reserve Bank oversight isn’t the same as putting it beyond oversight.

At least under Fed Reserve oversight means it’s under the oversight of financial professionals. Under present Congressional oversight means it would be overseen by a Republican Congress that frankly wants it to fail. Putting it under the Fed insulates it from meddling by conservative politicians who want to wreck it, so that’s a goods thing.

As to regulatory capture, this might just be a danger to be guarded against, given the current setup, rather than a problem for which there is a final solution.

@Grumpy Realist:

That hasn’t really prevented regulatory capture. (e.g. the relationship between the Japanese nuclear regulators and TEPCO leading into the Fukushima Daiichi disaster).

The number of regulations grows like wildfire. The efficacy of the regulations is highly dubious, if not out and out counterproductive. But no one can think of a solution.

That speaks volumes.

@Guarneri: I’m as small government as the next guy but I don’t see a solution here. The financial sector, like many others, is simply too complicated for ordinary folks to be able to navigate in a caveat emptor fashion; we simply can’t reasonably expected to understand the terms. That requires regulation. But that’s complicated, even in a world without regulatory capture and other malfeasance, by the fact that industry will always be two steps ahead of the regulators.

Dear Dr. Joyner,

We are in fundamental agreement that the relationship between the watchdog and the watched allows for an advantageous role for narrow interests over the interests of the entire country. The revolving door is one mechanism of this problem. You emphasized the formal barriers that have been erected; I think that a lot of stuff isdone informally. Our laws and regulations don’t come from a burning bush, but they are written by people. I believe that much of the text of our laws is written by technical staff that is part of the revolving door population which is the reason I brought this up.

@James Joyner: It has become more apparent to me lately – and I see it in comments like Jenos’ – that there is an implicit belief held by many sophisticated people that, if only some other party or politician was making the decisions there would be no problems, no complications, no blow back, no unforeseen collateral issues. Unfortunately, running a government, running an economy, running a society (or, frankly, living your own life) is hard, complicated work. Some policies are better than others. Some politicians are smarter than others and some are more honest or dishonest than others. But judging your opposition as bad intentioned simply due to a failure of perfection in the outcome or by an absence of any collateral problems is complaining from a fantasy vantage point.

Nice balanced piece James. You seem to forget that there is an option of taking these people, and their returning, to academia. Of course that has its own issues.

Steve

@Stormy Dragon: Ah yes. I used to work at a very obscure institute under the Science and Technology Agency aegis–we joked that the guys picked to head up our organization were the people who had to get whisked out of public view for six months whenever something embarrassing happened with one of Japan’s nuclear power plants. (Not that they had ever been actually responsible for anything, mind you–just that they were the poor bastards in the wrong spot when something had happened.) They usually spent the first half of their time making the rounds of the government offices in “getting to know you” visits and the latter half doing the same with “I’m about to leave” visits. While all of us researchers would just continue doing on what we had always been doing and ignoring them as much as possible.

(This was before the powers that be decided to meld STA together with Mombusho, which was an ill-matched marriage if there ever was one. Totally different cultures. Those of us in STA would have much preferred getting mashed together with MITI.)

As others have suggested above, historically the solution to this problem was a fully functional bureaucracy populated by nonpartisan career professionals. It’s not agile, but it avoids many of the problems noted above, including regulatory capture.

In the US, we had that in at least some sectors of the government until one of our two parties began deliberately sabotaging the bureaucracy as part of a campaign to prove that government is itself the problem. As a result, we have moved from (for example) a Department of Defense that used to employ tens of thousands of competent engineers in both design and oversight roles, to one that employs a handful of less-qualified engineers in led-around-by-the-nose roles, while at the same time coping with a crushing burden of contradictory and counterproductive statute.

It is certainly true that the Executive Branch is terrible at regulatory oversight these days. That’s not surprising, given the deliberate evisceration of the regulatory agencies that’s been going on since Reagan. We used to be much better, and it’s not an accident that we got worse.

@DrDaveT: This is, of course, the ultimate regulatory capture — when the money that wishes not to be regulated or taxed controls the legislature to an extent that enables them to dismantle regulation and taxation and government itself.

@steve: Academia and think tankery are indeed viable options for many of these folks, although there are only so many of those posts to go around and a lot of competition. But the ones who were high-powered lawyers before going into government service aren’t likely to permanently give up high earning potential for the opportunity to serve. I’m not sure that’s even a reasonable expectation, even aside from the limiting of the talent pool that it would naturally create.

@Joe: “It has become more apparent to me lately – and I see it in comments like Jenos’ – that there is an implicit belief held by many sophisticated people that, if only

some othermy party or politician was making the decisions there would be no problems, no complications, no blow back, no unforeseen collateral issues that I would care about.”FTFY

@Jenos Idanian:

The primary motivator for these jumps is salary increases – enormous salary increases. The only way to truly nullify that factor is for the government to pay competitive compensation, which will never happen because 1) it can’t afford it and 2) the taxpayers would lose their collective minds.

When you conceive of a viable way to persuade $112k per year apparatchiks not to jump ship for seven figure compensation packages, please let the rest of us know how it works.