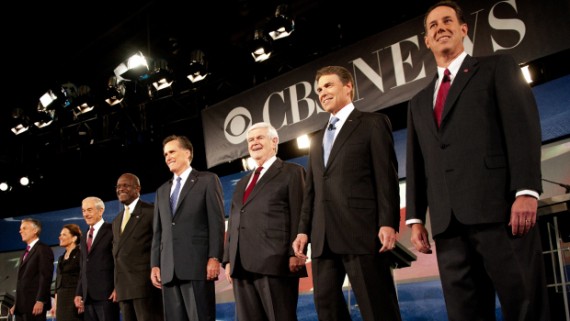

Republican Foreign Policy Debate: Winners and Losers

Huntsman will gain little if any traction and none of the frontrunners really helped or hurt themselves.

Most of the buzz around the first of the 2012 Republican debates devoted to foreign policy has been on the bizarre format. NRO’s Marc Thiessen: “If there was a loser on the debate stage tonight, it was CBS. First, they scheduled their debate on a Saturday night between two major football games. Then they decide to only broadcast the first hour of their 90-minute debate. Then their Internet feed failed for the final 30 minutes. This was CBS’s first and only debate–and it showed.”

As I joked on Twitter, they clearly got the idea from The Daily Show. Jon Stewart routinely overshoots the ridiculously short time allotted for interviewing the substantive guest of the evening, asks them if they can stick around for a few more minutes, and promises the TV audience that “we’ll put the whole thing on the Web.” Presumably, they’ve decided that, despite the fact that Stewart would rather spend another ten minutes talking to Bill Clinton than air a tediously long bit featuring Samantha Bee, the audience for a late night comedy show would not.

But I digress. In terms of the substantive discussion, opinions are all over the map, influenced both by the pre-existing preferences of analysts and the differing expectations of the ability of each candidate to put together a coherent sentence.

Brian Montopoli, Stephanie Condon, Corbett B. Daly of CBS focus on optics rather than substance and rank the candidates in order of how much they helped themselves:

Mitt Romney: Romney has been better than his rivals in presidential debates so often that it’s gotten to the point where a strong performance – as he had in this debate – feels almost ho-hum. Romney managed to be hawkish on issues like Iran while also leaving himself a little breathing room, playing to a Republican base that still views him skeptically.

And despite being widely seen as the frontrunner for the nomination, Romney didn’t take any serious blows from his rivals. (Gingrich notably declined to elaborate on his not-so-veiled criticism of Romney as little more than a competent manager who wouldn’t change Washington.) Romney’s only cause for concern: If he’s supposed to be the man to beat, why aren’t his rivals more eager to take him down?

Newt Gingrich: For one of the most substantive debates of the campaign, Gingrich’s depth and command of the issues allowed the former speaker to shine. Gingrich has been accused of scowling in prior debates, but his demeanor Saturday was markedly friendlier. And he scored points with conservatives in responding to a question from debate co-host CBS Evening News anchor Scott Pelley, who pointed out that al Qaeda recruiter and U.S. citizen Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed by U.S. forces without trial, was not convicted in court. You don’t get such privileges if you are at war with the United States, Gingrich said. He also offered more red meat to conservative base, who are looking for a consensus non-Romney candidate, when he said he would be willing to attack Iran to prevent the oil rich nation from obtaining a nuclear weapon.

Ron Paul: Paul is able to provide the biggest contrast with his rivals when he discusses his opposition to U.S. military intervention abroad and what he sees as civil liberties violations against U.S. citizens, and this debate gave him a chance to hit those notes repeatedly. Paul was passionate about issues like his opposition to waterboarding: “It’s illegal under international law and under our law,” he said. He also called it “immoral,” as well as the U.S. government killing U.S. citizens who are suspected of terrorism, saying, “I don’t think we should give up so easily on our rule of law.”

The polls suggest Paul’s brand of hardcore libertarianism has a limited appeal with GOP primary voters, and he remains a serious longshot for the Republican presidential nomination. But his goal is also to get his ideas into the public sphere, and on that front this debate was an unqualified success for him.

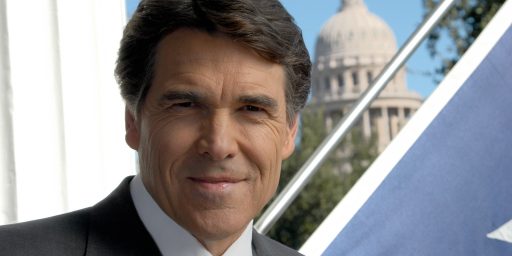

Rick Perry: By all measures, Perry exceeded expectations. He touted his military service and spoke passionately on counter-terrorism in way that would appeal to foreign policy hawks. And perhaps even more importantly, his performance was free of the gaffes that he’s become known for in debates.

He may have walked into a trap, however, when he answered a follow-up question regarding his proposal to “start at zero” when it comes to foreign aid. When asked via question about whether that policy would apply to Israel, Perry said “yes,” although he quickly confirmed his belief that Israel is a critical ally. The response could still prove risky for a Republican candidate when the GOP base so intensely supports Israel. Furthermore, commentators pointed out the U.S. has a 10-year agreement to provide Israel with about $30 billion for security assistance.

Michele Bachmann: Bachmann came to the debate prepared. She sounded well-versed on the ongoing war in Afghanistan and gave specific responses with respect to how she’d handle the war. She was quick to respond to Perry’s “start at zero” foreign policy, pointing out that applying that policy to a state like Pakistan — an unstable country with nuclear capability — could be risky.

One instance in which Bachmann’s performance faltered was during a debate over assassinating an American citizen living abroad who’s engaged in terrorism. The congresswoman seemed to miss the point of the question and said she approved of the order to kill Osama bin Laden – who was not, of course, an American citizen.

Rick Santorum: Santorum didn’t get as many questions as the more popular candidates in the polls, but when he did get a chance to talk, his remarks sounded thoughtful and measured. Presented with a hypothetical scenario of nuclear weapons from Pakistan going missing, the former senator insisted the U.S. would have to cooperate with the country. And while Santorum took an aggressive stance on the issue of Iran attempting to acquire nuclear capabilities, he was able to cite his history of working on the issue in Congress — an advantage over the other candidates.

Jon Huntsman: The former ambassador to China didn’t get to say much, but when he did he was able to articulate his vision clearly. Unfortunately for Huntsman, that may not matter for a candidate who is consistently at the bottom in polls of the GOP contenders. For the candidates less favored by GOP primary voters, breaking through to get airtime is always a challenge, and it was no different for Huntsman.

Herman Cain: Cain came into this debate having shown almost no knowledge on foreign policy issues, and the fact that he got through all 90 minutes without any serious gaffes has to be considered something of an accomplishment. But Cain also failed to put to rest concerns that he doesn’t have the knowledge to lead on the international stage, often offering vague and unspecific responses when pressed on details. The good news for the former Godfather’s Pizza CEO is that the election is almost certainly going to be decided on the economy, an area where he has shown himself to be far more convincing.

It’s amusing that simply not committing major gaffes is considered a win. Ditto that woeful ignorance of even the basic questions–not understanding that the “assassination” question was about Awlaki rather than bin Laden, for example–is considered a minor issue. But really this all points to the silliness of the format: Too many candidates on stage, too little time to have a decent discussion, and moderators playing favorites is just no way to learn much of anything useful.

Still, the above framework is probably the right way to judge these things. Voters aren’t foreign policy wonks and they’re mostly judging these candidates viscerally–do they have “the right stuff” to be commander-in-chief–rather than in terms of their expertise.

In terms of substance, most of the credible candidates said roughly the same thing on Iran: that military action has to be on the table but should be used only if all other actions (including, as Gingrich noted, covert action) failed. Herman Cain was the most reluctant of the frontrunners on the use of force, preferring instead assisting the Iranian opposition movement, such as it is. Ron Paul was the interesting outlier, emphasizing the need to get congressional approval for any action and noting ”I’m afraid what’s going on right now is similar to the war propaganda that went on against Iraq.”

Paul and Huntsman took the strongest stances against waterboarding, with both stating directly that it’s “torture” and not only illegal but a violation of American values. Huntsman hit the ball out of the park on that one, declaring “We diminish our standing in the world and the values that we project which include liberty, democracy, human rights and open markets when we torture,” adding, “We should not torture. Waterboarding is torture. We dilute ourselves down like a whole lot of other countries and we lose that ability to project values that a lot of people in corners of this world are still relying on the United States to stand up for.”

But that’s not the popular answer in a Republican debate. Perry, naturally, was the most pro-torture of the candidates, declaring, “for us not to have the ability to try to extract information from [terrorists] to save our young peoples’ lives is a travesty. This is war. That is what happens in war.”

On Afghanistan, Paul and Huntsman were both forceful advocates for withdrawing American forces. Romney rejected the notion of negotiating with the Taliban while Gingrich, correctly, said that it’s hard to imagine how you’d win the war without reaching a settlement with them.

Romney and Gingrich endorsed the notion of killing American citizens who were accused of terrorism; Bachmann did, too, although she clearly didn’t understand the question. Gingrich declared, ”if you engage in war against the United States, you are an enemy combatant” and therefore lose the expectation of due process.

Paul was the only candidate to oppose the war on terror outright. ”We’re pretending we’re at war, we haven’t declared war, but we’re at war against a tactic, and therefore there’s no limits to it.”

Huntsman is clearly the most seasoned foreign policy hand in the field. He’s trying desperately to capitalize on that, including launching a new ad in the run-up to the debate. But it just doesn’t seem to matter. Not only is the economy, not foreign policy, clearly what voters are interested in this cycle, he’s unable to get above 2 percent in the polls. And, as Politico‘s Reid Epstein notes, Huntsman was all but ignored by the moderators.

When the Republicans gathered for their first debate focused on foreign policy Saturday, the candidate with the most foreign policy experience got left in Siberia. That’s how Jon Huntsman, a former ambassador to China and Singapore, described the feeling of waiting 40 minutes into the National Journal/CBS debate for what was his second question of the night.

And, whether because of personality or the 13th Commandment, Huntsman didn’t capitalize on the few chances he got.

Huntsman was reluctant to take the kind of swings on stage that his campaign’s been making for him in the hopes of gaining some traction.

Rather than attack Romney his suggestion that the United States formally accuse China of currency manipulation at the World Trade Organization, Huntsman used a question about China as a quiet, teachable moment.

“First of all, I don’t think, Mitt, you can take China to the WTO on currency-related issues,” Huntsman said. “Second, I don’t know that this country needs a trade war with China. … So what should we be doing? We should be reaching out to our allies and constituencies within China. They’re called the young people, they’re called the internet generation.”

Asked about the European debt crisis, he used the time to answer a previous question about what to do if Pakistan lost control of a nuclear weapon by explaining the back story, name-checking Pakistani Gen. General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and President Asif Ali Zardari.

[…]

The result: in 90 minutes on stage, Huntsman spoke for just over six minutes. He didn’t try to get more time, unlike Bachmann, who repeatedly tried to interject — and who, along with Ron Paul, immediately after launched an attack on the debate sponsors for limiting her speaking opportunities.

“What can you do?” Huntsman said, when asked in the spin room about his lack of time. He added: “These aren’t perfect venues for the American people to kind of absorb what’s in our heads about these issues. And it’d be nice if we could somehow reconstitute them in ways that provided a little more time on the issues that really do matter.”

This is all very appealing to Republicans like me. There are perhaps a hundred of us.

My guess, then, is that Huntsman will gain little if any traction and that none of the frontrunners really helped or hurt themselves. Bachmann helped cement the notion that she’s rather out there, with such things as declaring that Obama was setting up a “worldwide nuclear war against Israel” with poor policy choices or that he’s “allowing the ACLU to run the CIA” when he’s just appointed the most prominent American field general since WWII to run it, but it’s been some time since anyone took her seriously as a candidate, anyway.

Perry likely helped himself a little just by not coming across as an idiot. Additionally, he showed some humor in responding to a question about what he’d do with the Energy Department’s nuclear weapons program if he eliminated the agency with the quip, “Glad you remembered it.”

The likely eventual nominee, Mitt Romney, didn’t give answers that satisfy me on every front but he’s not alienating anyone, either. That’s both how he’s kept his frontrunner status against a bevy of flavor of the week candidates and the reason that he hasn’t put the field away.

“This is all very appealing to Republicans like me. There are perhaps a hundred of us.”

In other words you prefer watching Democratic debates.

I’d say it’s more like 10,000, but that’s effectively the same number.

Heck, I like Huntsman and think he’s by far the best of the bunch and I’m not even a Republican.

@Fiona: I like Hunstman too. I strongly disagree with some of his positions, but he can be reasoned with.

No question that Huntsman is the most qualified to be President. But, as we saw with VP candidate Palin, qualifications mean bubkis to the Republican base.

I could see myself voting for Huntsman.

An important consideration for me would be that the Republican congressional caucus, which has been intentionally holding back the recovery for political purposes, would finally be forced to get serious about the economy. On the other hand rewarding Republicans, for what amounts to treasonous actions, would be wrong.

At least Huntsman leaves it in a conundrum. None of the other candidates are worthy of consideration. Could Huntsman pull a Clinton and come from no-where to win???

James- Mitt has at least a couple of decent advisors. He has been running for this office for years. Does he just not care? I expected better from him.

Steve

@Steve: He’s stuck doing what frontrunners do–taking popular positions or no positions at all. Obama more-or-less did that in 2008.

Romney’s “position” on Iran was silly. That was not the statement of a thoughtful candidate, it was nonsense.

Norm, your accusations of treason are no less hyper-partisan, laughable and worthy of ridicule coming from a liberal than they are coming from a conservative.