Senate To Consider Syria AUMF With Time Limits, No Ground Troops

A proposed Syria authorization being considered in the Senate places several limits on Presidential authority to act, but it's unclear if those limits can actually work.

The Senate Foreign Relations Committee is reportedly set to consider an Authorization For The Use Of Military Force (AUMF) in Syria that at least purports to place serious limits on the President’s power:

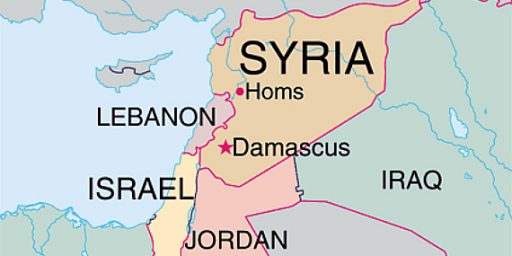

Senate Foreign Relations Committee leaders have reached an agreement on the language for the resolution authorizing the use of force against Syria for up to 90 days — but with no “boots on the ground.”

“Sharing President Obama’s view that our nation is best served when we come together as one, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee has crafted a bipartisan Authorization for the Use of Military Force that we believe reflects the will and concerns of Democrats and Republicans alike,” Chairman Robert Menendez said Tuesday in a statement. “Together we have pursued a course of action that gives the President the authority he needs to deploy force in response to the Assad regime’s criminal use of chemical weapons against the Syrian people, while assuring that the authorization is narrow and focused, limited in time, and assures that the Armed Forces of the United States will not be deployed for combat operations in Syria.”

The New Jersey Democrat scheduled a markup for Wednesday. Earlier Tuesday, Menendez noted that the new resolution would not permit American boots on the ground.

As drafted, the language worked out between Menendez and ranking member Bob Corker, R-Tenn., would authorize the use of force for 60 days, with provisions making it possible that the authorization would be extended for 30 days after that, according to Senate sources.

The draft Senate resolution, which is embedded below, is far broader than the resolution proposed by the White House on Saturday, which reads this way in its pertinent parts:

(a) Authorization. — The President is authorized to use the Armed Forces of the United States as he determines to be necessary and appropriate in connection with the use of chemical weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in the conflict in Syria in order to —

(1) prevent or deter the use or proliferation (including the transfer to terrorist groups or other state or non-state actors), within, to or from Syria, of any weapons of mass destruction, including chemical or biological weapons or components of or materials used in such weapons; or

(2) protect the United States and its allies and partners against the threat posed by such weapons.

In the days since the President sent this matter to Congress, many members on both sides of the aisle have expressed concerns about the open-ended nature of the White House’s proposed resolution, while others have suggested that such a broad grants of authority would have a tough time making it through the House of Representatives. In some senses then, it seems clear that this proposed Senate resolution is meant as a pre-emptive attempt to appease the enough House members to make passage more likely. Indeed, it’s worth noting that the proposals currently floating among House members are fairly close to what the Senate committee is set to consider later today:

A pair of House Democrats and a senior House Republican on the Intelligence Committee have released new draft resolutions dealing with President Barack Obama’s authority to attack Syria, illustrating the resistance to the White House’s initial proposal.

The two House Democrats — Virginia Rep. Gerry Connolly and Maryland Rep. Chris Van Hollen — say Obama wants “far too broad authority” to attack Syria. Meanwhile, Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) wants Obama to present further evidence to justify any military intervention.

The House isn’t even yet in session, but the resistance to the proposal shows that Congress is eager to influence the United States’ plans in the region.

Nunes proposal could be attractive to House Republicans, many of whom are solidly against attacking Bashar Assad’s regime in Syria. A draft copy of his bill, provided to POLITICO, requires Obama to come to Congress within 60 days to provide information in nine areas to justify the use of force.

The bill would require an explanation of attempts to build a coalition; a “detailed plan for military action in Syria, including specific goals and military objectives;” what would qualify as degrading the chemical weapons supply; an explanation how a limited military strike would encourage regime change, prevent terrorists from taking control of power or weapons, secure the chemical weapons and deter their future use; how a strike would prevent Iran and Russia from keeping Assad in power; information about Al Qaeda’s access to weapons; an explanation of whether weapons from Libya are being used by the Syrian opposition and an estimation of the cost.

In contrast, Van Hollen and Connolly are supportive of strikes against Syria, but they think Obama’s language “could open the door to large scale military involvement in Syria and the region.”

“We will not support that resolution,” the pair write in a letter to their colleagues.

Their resolution prohibits ground forces in Syria, limits attacks to 60 days and prohibits Obama from attacking again, unless Obama says that Assad’s regime uses chemical weapons again. The resolution also says Obama can only attack Syria with the goal of preventing use of chemical weapons, not to prevent the stockpiling of them

The time limits set forth in both of these competing resolutions is close in many ways to the time limits set forth in the War Powers Act, and it strikes me that there are rather obvious reasons for that. At the same time, though, these limits raise the same questions that the War Powers Act does, namely what does Congress do if and when a President decides to disregard the time limits that the resolution sets up him. Like the WPA, the resolution has no real enforcement provisions, and past history makes clear that the Federal Courts would be reluctant to involve themselves in a dispute between the Executive and Legislative Branches over an issue like this. In such a situation, the only power that Congress would have to enforce the resolution would be to cut off funding for military operations. Ever since they War Powers Act became law over President Nixon’s veto, President’s have operated under the belief that Congress would never really have the guts to vote to cut off funding while U.S. forces remain in a dangerous or potentially dangerous situation. That same history indicates that they have been largely right about that fact. Of course, Congress could go forward with an impeachment proceeding in such a situation as well, but that also seems unlikely. As a result, it’s unclear if the limits that the Senate resolution has are worth the paper that they’re printed on.

Here’s the text of the Senate resolution. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee will begin the process of discussing this language within the hour:

I’m glad the Congress is moving in this direction. At the very least it’s bringing the authorization into concurrence with what the president has said about what he wants to do which should bring some clarity to the situation.

The resolution tries to reconcile the irreconcilable: Limit the operational scope but provide sufficient authority to deal with contingencies.

Good luck with that.

You’d think that calling for limits and then receiving them would be more satisfying.

It doesn’t matter what kind of resolution is passed because if we bomb Syria, you can bet a reason to keep bombing Syria including sending troops in will be found later on.

This whole attack Syria agenda is in accordance to the will of the Industrial/military complex that Ike warned Americans about. Obama and his cronies don’t care about Syrian civilians being gassed.

What was accomplished in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya? Destabilization is what was accomplished.

So now we are being sold that 90 days of bombing is somehow going to accomplish some kind of good for the Syrians. Madness is what it is. WW3 is about to start because of this and every country in the world is going to be affected one way or another.

God loves you all very much, prepare yourselves.

How many times has the US got into these situations and actually thought there there can be a limited war? Things do not work that way. Maybe that is the problem. Maybe should be a rule that if there is to be any involvement it has to be done with no limits. Then they would decide it is not worth it. “a full retaliatory response” (Kennedy, 1962).

“You want a war you can’t win?” (Colonel Troutman)