Sex Selection Abortions Lead to 160 Million ‘Missing’ Girls

160 million girls are "missing" owing to selective abortion and cultural preferences for male children.

Erik Loomis offers a remarkably uncharitable summary of Ross Douthat‘s latest column: “I Believe, Through the Very Selective Reading of a Book I Picked Up, That Empowering 3rd World Women Leads to Aborting Girls. Therefore, Let’s Reinforce Patriarchy.”

Douthat, a socially conservative devout Catholic, is anti-abortion. But his treatment of the subject isn’t hyperbolic, much less misogynistic:

In 1990, the economist Amartya Sen published an essay in The New York Review of Books with a bombshell title: “More Than 100 Million Women Are Missing.” His subject was the wildly off-kilter sex ratios in India, China and elsewhere in the developing world. To explain the numbers, Sen invoked the “neglect” of third-world women, citing disparities in health care, nutrition and education. He also noted that under China’s one-child policy, “some evidence exists of female infanticide.”

The essay did not mention abortion.

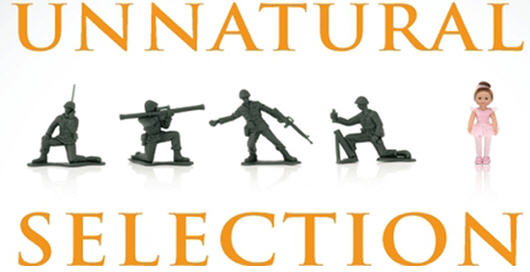

Twenty years later, the number of “missing” women has risen to more than 160 million, and a journalist named Mara Hvistendahl has given us a much more complete picture of what’s happened. Her book is called “Unnatural Selection: Choosing Boys Over Girls, and the Consequences of a World Full of Men.” As the title suggests, Hvistendahl argues that most of the missing females weren’t victims of neglect. They were selected out of existence, by ultrasound technology and second-trimester abortion.

Does he lament the passing of the patriarchy? Not so I can tell. He just says that its absence doesn’t end sex selection.

The spread of sex-selective abortion is often framed as a simple case of modern science being abused by patriarchal, misogynistic cultures. Patriarchy is certainly part of the story, but as Hvistendahl points out, the reality is more complicated — and more depressing.

Thus far, female empowerment often seems to have led to more sex selection, not less. In many communities, she writes, “women use their increased autonomy to select for sons,” because male offspring bring higher social status. In countries like India, sex selection began in “the urban, well-educated stratum of society,” before spreading down the income ladder.

Moreover, Western governments and philanthropic institutions have their fingerprints all over the story of the world’s missing women.

From the 1950s onward, Asian countries that legalized and then promoted abortion did so with vocal, deep-pocketed American support. Digging into the archives of groups like the Rockefeller Foundation and the International Planned Parenthood Federation, Hvistendahl depicts an unlikely alliance between Republican cold warriors worried that population growth would fuel the spread of Communism and left-wing scientists and activists who believed that abortion was necessary for both “the needs of women” and “the future prosperity — or maybe survival — of mankind,” as the Planned Parenthood federation’s medical director put it in 1976.

For many of these antipopulation campaigners, sex selection was a feature rather than a bug, since a society with fewer girls was guaranteed to reproduce itself at lower rates.

Does he advocate the return of the patriarchy? No. Indeed, he doesn’t really advocate any explicit change in policy in the column. Presumably, he would outlaw abortions generally and those on the basis of sex selection in particular. But to argue that this is “reinforc[ing] the patriarchy” solely on the basis that women are the ones who carry babies is, at best, ridiculously lazy.

Now, I haven’t read Hvistendahl’s book, so don’t have a strong sense of whether Douthat’s reading of it is “selective.” But it does seem to comport with the PublicAffairs Books, Amazon, Council on Foreign Relations, and Wall Street Journal summaries. Joshua Kurlantzick’s review, in particular, comports with Douthat’s take:

As news of these imbalances has spread, many have blamed ancient preferences: India’s patriarchal social systems, for instance, or Chinese beliefs that only boys provide for ageing parents. Hvistendahl’s research puts the lie to these lazy claims. In reality the wealthier parts of developing nations often see the most skewed ratios, showing that modernisation and progressive views on female children do not always go together.

Instead, the easy availability of ultrasounds in developing cities often hardens sex preferences, because families can find out their child’s sex and abort the foetus with few social or legal sanctions. Sex selection via ultrasound may be illegal, but small bribes can easily convince technicians to skirt the laws. Some prominent hospitals now even advertise their skills in this area.

The West’s population-control policies of the 1950s and 1960s, fuelled by fears of dwindling resources in the developing world – fears that proved inaccurate – are also to blame. Indian doctors received funding and training from American groups, coming home determined to facilitate sex selection in their own country. Chinese officials also forced women to abort second children. As one sign Hvistendahl saw, touting the government line, declared: “You can beat it out! You can make it fall out! You can abort it! But you cannot give birth to it!”

Bachelor nations are dangerous for women too. Hvistendahl follows one typically depressing story, of a woman kidnapped in Vietnam and brought to China by a trafficking syndicate and forced into prostitution, having sex with tens of men each day. This woman is rescued, but returns to Vietnam scarred, and infected with HIV.

The grim consequences of this approach are now being felt. Marriage, scientists suggest, makes men more peaceable, lowering testosterone and lessening violence. Hvistendahl chronicles how China’s new permanent bachelors are buying up weapons, while crime rates are rising in those Indian and Chinese cities with the most skewed ratios. For now these angry young men find outlets in guns and drugs, but if they united they could spark greater instability – as in the 19th century, when unequal ratios contributed to rebellions in the countryside that ultimately led to the overthrow of China’s last emperor.

What, if anything, should be done about this turn of events is debatable. That the situation is sad, if not outrageous, is not.

Look, it’s a choice. Period. To even bring up questioning motives is tantamount to denying that choice, and that’s not allowed. You shouldn’t even broach the subject.

At least, that’s what I’ve learned by listening to Planned Parenthood, NARRAL, NOW, and the like…

J.

My reading of the quotes does not square with Hvistendahl’s thesis that the patriarchy is not influencing selection. I don’t see any proof the women selecting the abortions are not buying in to a patriarchal value. The cultural preference is for males and the women are selecting for that. Upper class women, it seems to me, would especially select for it so as to not lose their status and be replaced by a woman who bears males.

I don’t think it’s limited to Third World countries. As I’ve mentioned before I serve as an election judge and the polling places in which I serve are typically school gyms or multi-purpose rooms. Routinely at some point in the day one or several classes are trooped through the polling place so the kids can see democracy in action.

Whenever that occurs I make a point of counting the students by gender. Over the last decade or so in none of the classes have the girls outnumbered the boys and boys frequently outnumber girls by a substantial margin.

Well, at this point, we are pretty much left with video games and internet porn. It’s not like you can produce a balancing crop of girls to make up the difference.

But diversion into useless pursuits may be the plan. That doesn’t bode well for the progressive plan to extract a percentage of their earnings for social programs though. Single men can live quite well on a reduced salary while spending their time on solitary pursuits. Of course, some geek may perfect the sexbot but then that could result in very low need to encumber themselves with marriage.

It is not like we can count on them being peaceable like the excess of girls in England, France and Germany after WWI.

Interesting, in the US adoption apparatus, the premium is placed on girls. A lot of times you can’t gender-specify a girl unless you already have a boy. But you can gender-specify a boy.

As news of these imbalances has spread, many have blamed ancient preferences: India’s patriarchal social systems, for instance, or Chinese beliefs that only boys provide for ageing parents. Hvistendahl’s research puts the lie to these lazy claims. In reality the wealthier parts of developing nations often see the most skewed ratios, showing that modernisation and progressive views on female children do not always go together.

The research does not put the lie to claims that Chinese parents want a boy to care for them in old age. From what does Kurlantzick draw that conclusion? Because China has a few millionaires now? Silly.

Please note that the trend predates Roe v Wade, and women still outnumber men in United States. More interestingly, to me anyway, women certain outnumber men in college — by a wide margin.

Realistically, I think it will continue until the economic and social problems of the skewed sex ratio are so strong that it forces changes in the cultural traditions driving the male preference that the new well-off people are ultimately choosing.

I would like to add one important qualifier to this, regarding India’s sex-imbalance. I’m trying to find the article, but it pointed out that you really see the massive son-preference and female abortion/infanticide with the second child. There isn’t a massive male preference with the first one.

Three things:

1) Maybe this was the point that Sam was making: it is a natural result of our biology that more boys are born than girls. Boys, on the other hand, have a higher death rate. This small difference in birth rates should not be confused with un-natural selection, but it does need to be deducted from the overall numbers to get an accurate figure.

2) At least in China, as more women enter the workforce and succeed, there is a trend (no idea how big) to view women as both having the resources to take care of an elderly parent and more likely to do it well.

3) I read the Ross Douthat piece, but was not clear what his overall point was. It seemed to be something along the lines that Western Liberals are responsible for sex-selection because they trained third world doctors to use ultra-sounds. Or something. Look, Douthat considers abortion murder, and he is upset that there are those among us that disagree. Bottom line is that he is bemoaning the fact that we don’t feel guilty and responsible for something he thinks we are guilty and responsible for.

At least in China, as more women enter the workforce and succeed, there is a trend (no idea how big) to view women as both having the resources to take care of an elderly parent and more likely to do it well.

Chinese women moved into the workforce en masse with the rise of communism. While circumstances have certainly changed since then, employment of Chinese women is not new.

Moving beyond Confucian traditions of male children caring for their parents will take time. For now, they have their “little emperors,” who have the bear the weight of expectation that traditionally was spread across a large family.

Mantis, it is certainly complex, but I think the influx of women into well paying professional jobs, who come back home during the holidays with gifts for the whole family, is a fairly recent phenomena. I’ve been in China 90 days over the past eight months, mostly Shanghai (which is to China what Manhattan is to the US) and will be moving there for a three year stint in August, and have been surprised by the number of ambitious and serious professional women in the workforce.

One summation of Hvistendahl’s argument that set off my alarm was:

I need to check in with some Anthropologist friends who work in these areas (SE and South Asian Cities), but this quote strikes me as a bit odd — or at least throwing a lot of responsibility of women (versus the family as a whole) for choosing to abort girls.

On the subject of paternalism – it influences things in both explicit and subtle ways. For example, at least in India, traditional institutions like Marriage dowries still exist and are very much practiced. With the average cost of an urban Indian wedding now exceeding $30K (with a far lower level of average income — even among the middle class), there are strong financial incentives *NOT* to have a girl.

Good luck in China, MM!

I learned Mandarin in college and spent five months there in 2004. I haven’t been to Shanghai, unfortunately, but given that it is China’s most international, cosmopolitan city (aside from Hong Kong), it doesn’t surprise me. I think the rise of a Chinese professional class has been true for both genders in recent years, but if it is pushing them away from this focus on male children as old-age insurance, that’s a good thing!

If you get a chance to visit Xi’an, and you haven’t already, don’t miss it. The old capital still has it’s wall, and it’s a great way to see old China in a way you won’t in Beijing (and definitely not Shanghai).

Thanks for the well wishes, mantis.

And on another subject: Wow, an actual intelligent discussion on OTB. Just like the old days.

For the record, I’d like to note that not one person responded to my snark at the opening.

Thank you.

Considering the turn of this discussion, I shoulda said nothing here.

J.