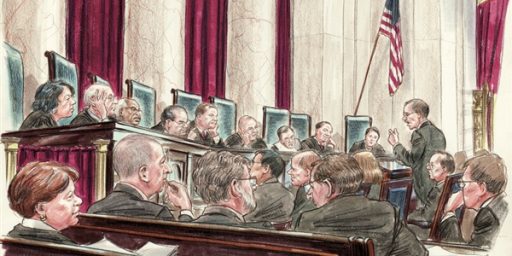

Supreme Court Appears Sympathetic To Some Parts Of Arizona Immigration Law

The Solicitor General had another bad day in Court yesterday.

Keeping in mind the caveats about basing predictions about the outcome of a case that I noted prior to the Supreme Court’s hearings on the Affordable Care Act, yesterday’s oral argument on the Constitutionality of Arizona’s controversial immigration law would appears to indicate that there’s at least some sympathy on the Court for the state’s position, and skepticism about the argument the Federal Government is making:

WASHINGTON — Justices across the ideological spectrum appeared inclined on Wednesday to uphold a controversial part of Arizona’s aggressive 2010 immigration law, based on their questions at a Supreme Court argument.

“You can see it’s not selling very well,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a member of the court’s liberal wing and its first Hispanic justice, told Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli Jr., referring to a central part of his argument against the measure.

Mr. Verrilli, representing the federal government, had urged the court to strike down a provision requiring state law enforcement officials to determine the immigration status of people they stop and suspect are not in the United States legally.

It was harder to read the court’s attitude toward three other provisions of the law at issue in the case, including one that makes it a crime for illegal immigrants to work. The court’s ruling, expected by June, may thus be a split decision that upholds parts of the law and strikes down others.

A ruling to uphold the law would be a victory for conservatives who have pressed for tough measures to stem illegal immigration, including ones patterned after the Arizona law, in Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina and Utah. President Obama has criticized the Arizona law, calling it a threat to “basic notions of fairness.”

Should the court uphold any part of the law, immigration groups are likely to challenge it based on an argument that the court was not considering on Wednesday: that the law discriminates on the basis of race and ethnic background.

Indeed, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. signaled that the court was not closing the door on such a challenge, making clear that the case, like last month’s arguments over Mr. Obama’s health care law, was about the allocation of state and federal power. “No part of your argument has to do with racial or ethnic profiling, does it?” he asked Mr. Verrilli, who agreed.

Wednesday’s argument, the last of the term, was a rematch between the main lawyers in the health care case. Paul D. Clement, who argued for the 26 states challenging the health care law, represented Arizona. Mr. Verrilli again represented the federal government. In an unusual move, Chief Justice Roberts allowed the argument to go 20 minutes longer than the usual hour.

The two lawyers presented sharply contrasting accounts of what the Arizona law meant to achieve.

Mr. Clement said the state was making an effort to address a crisis by passing a law that complemented federal immigration policy. “Arizona borrowed the federal standards as its own,” he said, adding that the state was simply being more assertive in enforcing federal law than the federal government. Mr. Verrilli countered that Arizona’s approach was in conflict with the federal efforts. “The Constitution vests exclusive authority over immigration matters with the national government,” he said.

Mr. Verrilli, whose performance in the health care case was sometimes halting and unfocused, seemed on Wednesday occasionally to frustrate justices who might have seemed likely allies. At one point Justice Sotomayor, addressing Mr. Verrilli by his title, said: “General, I’m terribly confused by your answer. O.K.? And I don’t know that you’re focusing in on what I believe my colleagues are trying to get to.”

The Arizona law advances what it calls a policy of “attrition through enforcement.” The Obama administration sued to block the law, saying it could not be reconciled with federal laws and policies. In legal terms, the case is about whether federal law “pre-empts,” or displaces, the challenged state law.

As a general matter, federal laws trump conflicting state laws under the Constitution’s supremacy clause. But no federal law bars the challenged provisions of the Arizona in so many words, and the question for the justices is whether federal and state laws are in such conflict that the state law must yield.

Lyle Denniston, as usual, has a great summary of yesterday’s argument:

In an oral argument that ran 20 minutes beyond the scheduled hour, the Justices focused tightly on the actual operation of the four specific provisions of the law at issue, and most of the Court seemed prepared to accept that Arizona police would act in measured ways as they arrest and detain individuals they think might be in the U.S. illegally. And most of the Justices seemed somewhat skeptical that the federal government would have to change its own immigration priorities just because states were becoming more active.

At the end of the argument in Arizona v. United States (11-182), though, the question remained how a final opinion might be written to enlarge states’ power to deal with some 12 million foreign nationals without basing that authority upon the Scalia view that states have a free hand under the Constitution to craft their own immigration policies. The other Justices who spoke up obviously did not want to turn states entirely loose in this field. So perhaps not all of the four clauses would survive — especially vulnerable may be sections that created new state crimes as a way to enforce federal immigration restrictions.

If the Court is to permit Arizona to put into effect at least some of the challenged parts of S.B. 1070, there would have to be five votes to do so because only eight Justices are taking part (Justice Elena Kagan is out of the case), and a 4-4 split would mean that a lower court’s bar to enforcing those provisions would be upheld without a written opinion. It did not take long for Justice Antonin Scalia to side with Arizona, and it was not much later that Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., showed that he, too, was inclined that way. Justice Clarence Thomas, who said nothing during the argument, is known to be totally opposed to the kind of technical legal challenge that the government has mounted against S.B. 1070.

That left Justices Anthony M. Kennedy and Samuel A. Alito, Jr., as the ones that might be thought most likely to help make a majority for Arizona. Their questioning, less pointed, made them somewhat less predictable. However, they did show some sympathy for the notion that a border state like Arizona might have good reasons for trying to deal with what Kennedy called the “social and economic disruption” resulting from illegal immigration.

The Court’s three more liberal Justices — Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Sonia Sotomayor — offered what appeared to be a less than enthusiastic support for the federal government’s challenge, although they definitely were troubled that S.B. 1070 might, in practice, lead to long detentions of immigrants. They wanted assurances on the point, and they were offered some by Arizona’s lawyer, Washington attorney Paul D. Clement.

Clement’s entire strategy (aside from an emotional plea that Arizona had to bear the brunt of the wave of illegal and often dangerous immigrants) was to soften the seemingly harder edges of the 2010 state law that set off a wave of new state and local legislation to control the lives of foreign nationals living illegally in the U.S. To each question Wednesday about how S.B. 1070 would work if put into effect, Clement pared down the likely impact and insisted that Arizona was only seeking to be a cooperative junior partner in enforcing federal laws and policies against undocumented immigrants.

The Solicitor General, by contrast, clearly did not have a very good day yesterday. Based on the reports, even the Court’s liberal members seemed skeptical of the arguments he was making against the Arizona law. At one point, for example, he seems to completely lose Justice Sotomayor when he essentially argues that it would be acceptable for individual Arizona law enforcement officers to cooperate with Federal immigration authorities, but that it’s somehow unacceptable for that kind of cooperation to be a matter of official state policy or law. More importantly, it seems that Verrilli never really managed to get his point across about what is likely the strongest part of the Federal Government’s challenge to SB1070:

[H]is national supremacy argument seemed regularly to falter, because the Justices as a group seemed much more interested in parsing just how the Arizona law would work in tandem with or, potentially, in conflict with federal policy. Verrilli, in fact, never quite got his point across about federal supremacy, and that showed in an exchange between him and Justices Alito, Kennedy, and Sotomayor.

Alito said he could not understand why Verrilli seemed to be saying that Arizona could not instruct its own state employees on how they should enforce the state’s own law, but rather that they should only do what federal authorities wanted them to do even though they don’t work for the federal government. The question seemed to indicate that Alito did not see that Verrilli was arguing that, since it was federal law that was at issue, federal priorities should govern.

Verrilli replied that, if a state wanted to cooperate in immigration enforcement, they needed only to bring to federal attention the fact that a given illegal immigrant was in the U.S. But Kennedy shot back that Alito was only talking about whose law state employees should enforce as a state priority. The Solicitor General then repeated the idea that the federal priorities should govern what state employees did, in the immigration context.

At that point, Justice Sotomayor said that the government argument left her “terribly confused.” She said she could not understand what was wrong with a system in which, if federal officials are contacted about an arrested immigrant and said they did not want that person detained, that person would have to be released. She was relying, of course, on attorney Clement’s assurance that that was what would happen if a federal official waved off the need for an immigrant to be detained further.

Chief Justice Roberts, though, went the furthest to try to discount Verrilli’s core argument about the disruption of federal immigration enforcement if Arizona were allowed to have its own style of enforcing immigration law. All that Arizona’s law required, Roberts suggested, was that a state officer let the federal government know that there was an illegal immigrant in its midst, and that did not force the government to do anything; it could enforce its ban on such immigrants or not. Somewhat sarcastically, the Chief commented: “If you don’t want to know who is in this country illegally, you don’t have to.”

Whether this ends up being an accurate statement of how this particular provision of SB 1070 would be enforced is rather beside the point, as are any legal challenges that might arise in the future alleging that the law is being enforced in a discriminatory manner. Clearly, the Court, and not just the conservative members of the Court, is skeptical of the Federal Government’s argument at this early stage. All in all, it was not a good day for the Federal Government’s argument. Ultimately, all of this doubt may end up meaning nothing. Unless the Court is able to come up with a majority on all, or even just one, of the issues before it then the decision below, in which the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the law was unconstitutional. Given Justice Kagan’s recusal, the possibility that this case could end in a serious of 4-4 ties on all four issues strikes me as being fairly high unless the skepticism expressed yesterday is so widespread that even the Court’s most liberal members end up handing the Federal Government a defeat, if not on the whole case then at least on the “stop and detain” provisions in the law.

It’s important to note what wasn’t before the Court yesterday. The Federal Government’s challenges to SB1070 make no allegations regarding racial profiling or the possibility that this law will be disproportionally enforced against people of Hispanic decent. In reality, this is the type of argument that really cannot be made until the law has actually been enforced and there’s some actual evidence, and more important actual Defendants, that the Court can look to in order to determine whether there are Equal Protection violations inherent in the law. Even if the law survives this challenge, then, the likelihood that we’ll see some kind of future litigation either by the Feds, or by private parties, is fairly high.

In all likelihood, we’ll be getting this decision in late June, around the same time as the ObamaCare ruling, and just in time for the General Election campaign to heat up. Whichever way it goes, it should be interesting.

Here’s the transcript of yesterday’s argument:

Clement vs. Verrilli is starting to look a lot like that first fight between Clubber Lang and Rocky.

Anyone else get the idea Verrilli didn’t want this job?

The hell? This smells like something that’s put in solely for the option of prosecutorial “piling on” – if they pick up someone, decide he’s illegal, and find money in his pocket, they can add this charge too.

Also,

This is the first I’ve seen of Scalia believing something that, to me, sounds embarrassingly preposterous. Is there a pointer to details on this? Does he really think we could function as a national entity with individual states running their own immigration? How does he feel about states printing their own money? Negotiating treaties with foreign powers? didn’t we have an entire civil war just to disprove things like that?

legion,

It already is a crime to employ someone who is in the country illegally.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’s body of work suggests otherwise.

It’s not as if Scalia will need to pay for his state’s immigration bureau, now is it? He’s just asserting that, in principle and writ, there’s nothing that says a state can’t do this crap. It’s entirely up to that state if it wants to waste money on redundant immigration services. The voter will decide things in the end.

If, as Doug suggests, the Administration could not bring the most powerful weapons to bear on these laws, the racial/ethnic profiling problems, then the Administration should probably not have mounted a weak facial challenge. A loss here will validate the laws and give amunition to supporters in other states.

It is starting to seem as though maybe Mr. Verrilli was not the best person for the job.

This strikes me as a very weird argument, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if a solid majority overturns the Federal argument. Being in the US illegally is a crime, is it not? Is holding a known criminal for the proper (in this case, Federal) authorities really a problem? If it is a problem, doesn’t that mean that a person that committed Murder in California effectively has sanctuary in Idaho? Or does the Arizona law go further than simply holding a known criminal and transferring them to the proper authorities?

I would not be surprised at all if Sotomayor joined a solid majority supporting Arizona, only to have a similarly solid majority overturn the law later on Equal Protection grounds (after it goes into effect).

@Doug Mataconis:

Actually, it’s a crime to knowingly employ someone who is in the country illegally, which is actually a significant distinction.

@Doug Mataconis: That’s not what this is saying – what you describe is a violation by _the employer_. This law is targeting _the immigrant_. Considering that the immigrant’s alternatives are starving or turning to crime, it seems more than a bit vindictive & wrong-headed to put into a law.

@legion: What I believe Scalia has been arguing is that in the federal immigration law, states are expressly authorized to create and enforce licensing and other laws concerning immigration. So, its not a state’s rights issue, it’s a federal grant to the states, the parameters of which are probably debatable and unclear, but Congress has the power to retract the grant.

OTOH, the Administration’s arguments about “exclusive authority over immigration matters” goes too far as well. This is probably a decent statement of the federal/state relationship from a very important SCOTUS decision::

@John D’Geek:

I’m pretty sure it is a civil infraction, and not a crime.

@Gromitt Gunn:

I’d argue it’s not illegal, in that the federal government does not have the constitutional power to limit immigration, and thus any law claiming to do so is invalid. The constitution grants the congress authority to determine rules for naturalization, not immigration.

The summaries of the arguments brought up a point that had escaped me before. Arizona isn’t really creating its own immigration laws — if it was, it would have its own punishments tied to the law. It’s simply reinforcing federal laws, saying that it will turn over illegal aliens to federal officials for their breaking federal laws.

And yeah, Verrilli’s arguments are incredibly weak. As one Justice noted, it roughly translates to “we don’t want to offend the Mexican government and the international community in general by actually enforcing the same kinds of laws pretty much every other nation on Earth has.” It is also consistent with the Obama administration’s policies in several other areas — the law is what they say it is, and they can unilaterally decide just what the law is and what it means.

They should lose this case because they deserve to lose it, because they are utterly wrong — both here, and in many other instances.

this is a case where the chances of this law, as actually implemented, NOT ending up with a horrible racial disparity between “Hispanics” and “non-Hispanics” is so miniscule as to be negligible.

Which means we can see coming down the pipe is the fact that at some point this law WILL be thrown out on constitutional grounds.

Sort of silly that we’re having all this legal kabuki at this point. We know what’s going to happen, just after many years of “your papers, pliz!”, pissed off tourists and Americans, a trashed Arizona economy, and who knows what else.

@Gromitt Gunn:

Being in the U.S. illegally is both a civil infraction under immigration laws and a crime. In most deportation cases, ICE chooses not to pursue criminal charges unless it is a case where someone has been caught in the country on multiple occasions after having been deported.

Entering the U. S. without a visa or at a place other than an official entry point is a crime punishable by fine and/or imprisonment under Section 1325 Title 8 of the United States Code.

@Dave Schuler: Good to know. Thanks. What about those who overstay their visas? Is there a law about “entering under false premises” or some such thing?

@grumpy realist: this is a case where the chances of this law, as actually implemented, NOT ending up with a horrible racial disparity between “Hispanics” and “non-Hispanics” is so miniscule as to be negligible.

Which means we can see coming down the pipe is the fact that at some point this law WILL be thrown out on constitutional grounds.

If only the Arizona legislature had put in some kind of language to specifically ban racial profiling, and require the cops to have a valid other reason to engage the subjects outside of their legal status.

Oh, that’s right, they did. Silly me.

And let’s be real, grumpy. The first test case of this will have at least a hundred lawyers fighting to take it, paid for by legal defense funds and hordes of liberal groups, and will insist that the whole incident was nothing but racial profiling and sheer racism. So I’m fully confident that the particulars of the law I cited will be followed to the letter — because the state officials will inform the police that they will come down like a ton of bricks if they start screwing around.

Despite the fact that the word “immigration” does not appear in the U. S. Constitution, the Supreme Court has ruled in Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong that the Congress does, in fact, have the power to regulate immigration. It is also generally argued that the power to regulate immigration is implicit in sovereignty.

BTW, if Congress did not have the power to regulate immigration then Arizona should definitely prevail in Arizona v. United States.

So far, this sounds like yet another attorney/fund raiser/columnist full employment measure. If the legal residence check passes muster, driving while Anglo may become interesting.

@PD Shaw: You are citing a footnote, you dork, that explains that a state may have a legitimate interest in affecting immigration into that state. Your quote has nothing to do with the actual federal/state relationship as determined by the plain language of the constitution and a couple hundred years of supreme court cases.

@Doug Mataconis: Hmm, okay. I had thought that entering without permission was a crime, but that being in the country without proper authorization was civil (i.e. someone who entered legally, but then stayed past their visa expiration).

People still don’t think that this court is cherry-picking state’s rights issues?

The implication of upholding Arizona’s law is that individual states may begin to establish their own immigration enforcement laws.

This is a very highly motivated conservative movement court.

@Doug Mataconis: “It already is a crime to employ someone who is in the country illegally. ”

Snort.

I’ll be that far more people are incarcerated (and put to slave labor) for being an illegal immigrant than for employing one.

@Tillman: “It’s entirely up to that state if it wants to waste money on redundant immigration services. The voter will decide things in the end. ”

That’s not what’s really at stake, of course. What’s at stake is whether or not Arizona can pass a ‘papers, please (if you’re brown)’ law.

@grumpy realist: “this is a case where the chances of this law, as actually implemented, NOT ending up with a horrible racial disparity between “Hispanics” and “non-Hispanics” is so miniscule as to be negligible.

Which means we can see coming down the pipe is the fact that at some point this law WILL be thrown out on constitutional grounds. ”

No, because Scalia, Roberts, Alito, Thomas and Kennedy know d*mn f*cking well that it is racial. They’re fools, they’re evil. They’ll pretend that it’s not SCOTUS’ place to question the workings of the police and prosecutors, since it’s a right-wing thing.

@Dave Schuler:

I didn’t realize SCOTUS rulings were delivered ex cathedra.

@Stormy Dragon:

For the last roughly 200 years legal is whatever the Supreme Court says is legal.

“immigration” is not Commerce under the Commerce Clause?

Say has all the real Americans flocking to Georgia to work in the fields brought down unemployment numbers yet?

@Barry:

I have always found it humorous that progressives argue that immigration laws are the same as racial profiling and thus, should not be enforced.

Of course, whites pay taxes are a much higher their percentage as a portion of the population. Maybe someone should point out that progressives taxes have a huge disparate impact and are therefore discriminatory.