Supreme Court Hears Oral Argument On Meaning Of ‘One Person, One Vote’ In Redistricting

The Supreme Court heard oral argument today in a case that could have big implications for redistricting, and the make-up of state legislatures and the House of Representatives.

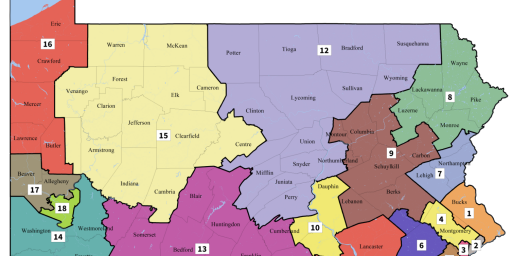

As Steven Taylor noted earlier, the Supreme Court heard oral argument today in Evenwel v. Abbott, a Texas case that could have a profound impact on how district lines at the Congressional and state legislative level are drawn throughout the country depending on how the court rules, and the Court appeared to be sharply divided on the issue:

WASHINGTON — A closely divided Supreme Court on Tuesday struggled to decide “what kind of democracy people want,” as Justice Stephen G. Breyer put it during an argument over the meaning of the constitutional principle of “one person one vote.”

The case basic question in the case, Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, is who must be counted in drawing voting districts: all residents or just eligible voters?

The difference matters, because people who are not eligible to vote — children, immigrants here legally who are not citizens, unauthorized immigrants, people disenfranchised for committing felonies, prisoners — are not spread evenly across the country. With the exception of prisoners, they tend to be concentrated in urban areas.

Their presence amplifies the voting power of people eligible to vote in urban areas, usually helping Democrats. Rural areas that lean Republican, by contrast, usually have higher percentages of residents eligible to vote.

The court’s decision in the case, expected by June, has the potential to shift political power from urban areas to rural ones, a move that would provide a big boost to Republican voters in many parts of the nation.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. seemed attracted to counting only voters. “It is called ‘one person one vote,'” he said. “That does seem designed to protect voters.”

But Justice Sonia Sotomayor said there were other interests at stake. “There’s a voting interest,” she said, “but there is also a representational interest.”

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy seemed to be looking for a middle ground. “You should at least give some consideration to the disparity you have among voters” in different voting districts, he said.

The “one person one vote” principle, rooted in cases from the 1960s that revolutionized democratic representation in the United States, applies to the entire American political system aside from the Senate, where voters from states with small populations have vastly more voting power than those with large ones. Everywhere else, voting districts must have very close to the same populations.

But the Supreme Court has never definitively ruled on who must be counted.

Tuesday’s case, a challenge to voting districts for the Texas Senate, was brought by Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger. They are represented by the Project on Fair Representation, a small conservative advocacy group that has been active in cases concerning race and voting.

The group was on the winning side in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder, which effectively struck down the heart of the Voting Rights Act, freeing nine states, mostly in the South, to change their election laws without advance federal approval. The group is also behind a challenge to affirmative action in admissions at the University of Texas at Austin to be argued on Wednesday.

In court papers, Ms. Evenwel and Mr. Pfenninger said that they lived in “districts among the most overpopulated with eligible voters” and that “there are voters or potential voters in Texas whose Senate votes are worth approximately one and one-half times that of appellants.

Last year, a three-judge panel of the Federal District Court in Austin dismissed the case, saying that “the Supreme Court has generally used total population as the metric of comparison.” At the same time, the panel said, the Supreme Court has never required any particular standard. The choice, the panel said, belongs to the states.

Almost all states and localities count everyone, and the Constitution requires “counting the whole number of persons in each state” for apportioning seats in the House of Representatives among the states. There are practical problems, many political scientists say, in finding reliable data to count only eligible voters.

Federal appeals courts have uniformly ruled that counting everyone is permissible, and one court has indicated that it is required.

In the process, though, several judges have acknowledged that the Supreme Court’s decisions provide support for both approaches. The federal appeals court in New Orleans said the issue “presents a close question,” partly because the Supreme Court had been “somewhat evasive in regard to which population must be equalized.”

In 1990, Judge Alex Kozinski, in a partial dissent from a decision of the federal appeals court in San Francisco, said there were respectable arguments on both sides.

Counting everyone, he said, ensures “representational equality,” with elected officials tending to the interests of the same number of people, whether they are voters or not. Counting only eligible voters, on the other hand, he said, vindicates the principle that voters “hold the ultimate political power in our democracy.”

Lyle Denniston has a summary of the argument:

In fact, the principle of “one person, one vote” has been understood as equality of districts, rather than voters, on the theory that everyone placed in each district — whether eligible to vote or not — is entitled to be represented by the winner. But there is a political movement now, increasingly active, that is pushing for the famous phrase to mean voter equality, so the process would start with making sure that those who are qualified to vote should wind up with roughly equal numbers in each district.

If there is great disparity between the numbers of eligible voters between districts, the theory goes, there is no voter equality: those in districts with fewer voters have considerably more clout, at election time, than those with many voters — even if the districts’ total populations are equal. A district over-populated with voters is said to dilute the ballot strength of each, compared to some other districts’ residents.

This equality theory was neatly captured by Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr. — although it was not clear whether he was really tempted to embrace it, or was just exploring its meaning. Suppose, he said, there was a rural district in which only nine percent of the population could vote, because its overall population is swelled by a large prison and none of the inmates can vote, but there is another district with about the same total population, but ninety percent of its residents can vote. “Is that okay?” he asked a federal government lawyer, Deputy Solicitor General Ian H. Gershengorn.

Gershengorn responded that the courts have recognized that legislatures, in drawing new districts, are entitled to rely on census data — that is, total population figures. There is no existing way, Gershengorn would go on to say, for the census to provide data that would aid legislatures in dividing up seats according to voter figures without simultaneously winding up with major differences in total populations. That, he indicated, would skew district population differences.

The theory was regularly disparaged by the more liberal Justices on the Court, who made clear they were not about to let the concept of representation be changed so that only voters were the constituents who counted in the writing of the laws. At least, they were not willing to make it unconstitutional to use total population as the starting point in redistricting, and mandating as the only constitutional norm the near-equality of voter populations among districts.

But the closest that any member of the Court came to suggesting serious consideration of the theory was Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, in a couple of remarks that were potentially telling. Most significantly, he asked Texas Solicitor General Scott A. Keller, who defended Texas’s use of total population: “Why does it have to be one or the other?” Both concepts, he said, may be worthy.

(…)

Kennedy could see at least the surface appeal of that spread (as a Justice, he is constitutionally devoted to equality principles), and wanted to know why legislatures could not strive for equal districts and equal distributions of eligible voters. Why, he asked Keller, is Texas not required to accommodate both interests? Keller’s response was the same as Gershengorn’s: district map-makers, he said, have to rely on census data, “and all we have is total population.”

Think Progress’s Ian Millheiser seems particularly concerned that the Justices are ready to adopt the Plaintiff’s interpretation of the “one person, one vote” rule in this case and lays out many of the implications that this would likely have going forward. As I’ve said before, however, it’s worth keeping in mind that oral argument is not always a good guide to determining just how a case will end up being decided. Frequently, Justices ask questions and take positions designed to test out an argument that is likely to come up during the conference where the Justices will take their initial discussion and vote on the case later this week, and the questions may be intended to try to steer the Justice’s conversation toward a certain aspect of the case. Additionally, it’s not uncommon for a Judge or Justice to play “devil’s advocate” during oral argument either for their own purposes, or to subtlely point out to a fellow Justice where their argument may be wrong, or may lead to unintended consequences. In the end, we really won’t know how the Court feels about this case until the decision is handed down some time next year. Additionally, as many observers have noted before this is very much an issue of first impression for the Justices since the question of whether “one person, one vote” means total population, total number of eligible voters, or some other measure that may be a combination of the two as Justice Kennedy suggests is not something that the Supreme Court has been asked to rule on before. Given all of that, I’d refrain from making any guesses about how the Court will decide this case based on oral argument alone.

That being said, based on the reading I have done of the pleadings in this case and the decision in the Court of Appeals below, it strikes me that the argument that ‘one person, one vote’ means that states must use only the number of eligible voters, or to make it even more restrictive just actual registered voters, is a misreading of the relevant Constitutional provisions. If the Founders had intended to say that Congressional districts should be drawn up based on the number of eligible or registered voters, for example, they could have very easily done so, and in their era the fact that the franchise was limited to white males, or in some states just white male property owners, would have meant that political power would have been apportioned quite differently than it ended up being at the time. Instead of using language such as that, though, Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, which provides that districts shall be “according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.” Over time, this provision was changed by the 14th Amendment to include all persons, including African-Americans, and Native Americans are now included by virtue of the fact that laws passed in the early 20th Century largely ended the idea that Native Americans living on reservations or tribal land were considered citizens of their respective tribes. Nowhere in the Constitution is there any real textual support for the idea that states should be restricted to counting only eligible or registered voters in drawing district lines.

In any case, as I said, we will see how the Court deals with this issue when the time comes. My suspicion is that the Court will ultimately be reluctant to adopt the radical standard that the Plaintiffs are asking for here, but that we may see an opinion that follows somewhere along the lines of the hybrid standard that Justice Kennedy mentions in his questioning. Exactly how that would work out, though, isn’t entirely clear, and it’s likely that the questions it would create would lead to years of litigation after every Census regarding redistricting on top of the litigation we already see. Given that, the Justices may be reluctant to add to the burden that these cases already place on the Federal Judiciary. As I said, we shall see.

Update: Buzzfeed’s Supreme Court reporter Chris Geidner has his summary of the argument up, and election law expert and law professor Rick Hasan offers six takeaways from the argument as well as an Op-Ed in The Los Angeles Times.

Here’s the transcript of today’s oral argument:

Will be fun to see how Scalia will justify going against “the plain language of the constitution”.

How closely related is this to gerrymandering issues?

“Excluding Indians not taxed”!

So, the states can remove the voting power of 47% of people with American Indian ancestors. More, perhaps, if they can show Indians are poorer than average.

Why is no one trying this?

I’m not prepared to argue this legally, but theoretically what would we want?

Surely children should be counted. If so, it would essentially give more voting power to their parents who represent them. (Obviously it would give more voting power to every other voter in the district as well.)

Personally, I’d probably even make the case for legal immigrants and prisoners (either of which could be related to eligible voters and could be indirectly represented by them).

But what about undocumented immigrants? Seems a bit of a stretch. Yes, they might *also* be related to legal, eligible voters, but why should they have any influence on our democratic process when they have unknown allegiance?

@Franklin:

Does a location need less infrastructure simply because it has illegal residents? Less cops? Less roads?

I just don’t see why the concerns of a city whose population consists of mostly of illegals should count less than a smaller city whose residents are legal. The city with more people has to deal with more things no matter the legal status of their residents.

Now that I see some of the comments here, I feel like this is very much “All citizens are equal, but some are more equal than others.” Can we just call all of this gerrymandering and place limits on the geometric complexity of district lines?

@Console:

So clearly Germans, who vacation disproportionately in southern Florida, should be counted in Florida totals so locals can vote the infrastructure spending required to handle them.

Allowing people to permanently stay in a country while not allowing them to vote is the recipe to create a large cast of political underclass. That became large problem in Germany that they changed their citizenship laws, there is a reason why countries in the American Continent are “jus soli”.

Besides that, the problem of elections in the United States is that people that vote(People that are older than the average) have too much political clout, not too little.

@Guarneri: There is a difference between a vacationer and a permanent resident.

One can be a permanent resident and still not be an eligible voter.

@Guarneri:

Well if you’re a “tourist” that makes the effort to come to the US the once a decade when the census is being conducted and magically manages to be included in the count then I suppose.

We aren’t reinventing the wheel here. A resident is a resident and there’s a way we count that. Been doing it for over 200 years.

If voting power is the issue, then the argument could lead to other ideas such as mandatory voting (we don’t want just voters to have too much power); all humans (children, etc) to be eligible voters; automatic and mandatory registration; and annual censuses (or how about real time population counting) to ensure that the 18 year old population has their full voting power taken into account.

@Console:

Why are we even talking the theory of this when this is obviously driven by a conservative law shop maintaining their grift by finding ways to reduce minority/Dem representation?

And how does Roberts get away with saying well, I guess “one person, one vote” means eligible voters when the guys who wrote ‘one person, one vote” did census residents? Let the b******s have this, they’ll be back in a couple years wanting to make it registered voters. They won’t quit ’til it’s back to white property owning males.

@Console: You seem to be equating voting power with more roads, which is a leap.

Yes, as a Californian, I hate that 18 million eligible voters suffer from voter inequality as our senate vote “counts” as much as the 240,000 Wyoming voters. Lets make the senate unconstitutional since it clearly violates the one man one vote doctrine of the wingnuts.