Supreme Court Takes On A Second Political Gerrymandering Case

The Supreme Court has agreed to hear a second case dealing with political Gerrymandering.

Yesterday, the Supreme Court announced that it had agreed to hear a second case involving political Gerrymandering, raising the potential of a pair of Supreme Court opinions that could have profound implications on how Congressional and state legislative district lines are drawn and, in turn, on the makeup of the House of Representatives itself:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court added a second partisan gerrymandering case to its docket on Friday, suggesting that the justices are seriously considering whether voting maps warped by politics may sometimes cross a constitutional line. The court has never struck down a voting district as an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

A ruling allowing such challenges could reshape American politics.

The earlier case, from Wisconsin, was argued in October. The new case, a challenge to a Maryland congressional district, differs from the first case in several ways. It was brought by Republican voters rather than Democratic ones; it is focused on a single district rather than a statewide map; and it relies solely on the First Amendment rather than a legal theory that includes equal protection principles.

When the first case, Gill v. Whitford, No. 16-1161, was argued, a majority of the court seemed at least open to the possibility that some kinds of partisan gerrymandering are unconstitutional. That case was a challenge to voting districts for Wisconsin’s State Assembly, which is dominated by Republicans notwithstanding very close statewide vote totals.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who probably holds the decisive vote in both cases, asked several questions about the First Amendment theory relied on by the challengers in the new case.

That case, Benisek v. Lamone, No. 17-333, was brought by Republican voters who said Democratic state lawmakers had redrawn a district to retaliate against citizens who supported its longtime incumbent, Representative Roscoe G. Bartlett, a Republican. That retaliation, the plaintiffs said, violated the First Amendment by diluting their voting power.

“The 2011 gerrymander was devastatingly effective,” the plaintiffs wrote in their appeal to the Supreme Court, saying that “no other congressional district anywhere in the nation saw so large a swing in its partisan complexion following the 2010 census.”

Mr. Bartlett had won his 2010 race by a margin of 28 percentage points. In 2012, he lost to Representative John Delaney, a Democrat, by a 21-point margin.

A divided three-judge panel of the United States District Court in Maryland denied the challengers’ request for a preliminary injunction. In dissent, Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, who ordinarily sits on the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, in Richmond, Va., wrote that partisan gerrymandering was a cancer on democracy.

“The widespread nature of gerrymandering in modern politics is matched by the almost universal absence of those who will defend its negative effect on our democracy,” wrote Judge Niemeyer. “Indeed, both Democrats and Republicans have decried it when wielded by their opponents but nonetheless continue to gerrymander in their own self-interest when given the opportunity.”

Lyle Denniston discusses the Court’s decision at his blog:

Friday’s order gave no explanation of why the Justices added the Maryland case, Benisek v. Lamone, to the docket for a decision in the current term. Already under review is the Wisconsin case, Gill v. Whitford, which the Justices have been studying in private since holding a public hearing on it on October 3.

The Court apparently is not yet ready to release a decision in the Wisconsin case, and that was one factor that made it a surprise that they were willing to move into the Maryland case now. It is quite common, when the Court already is reviewing a case raising an issue to hold other cases raising the same or a similar issue until after the initial one has been decided.

Although there are some key differences between the Maryland and Wisconsin cases, other than the fact that they involve elections at different legislative levels, they are close enough in scope that most observers expected that the Maryland case would have to await the outcome of the case ahead of it in timing, from Wisconsin. That expectation rose when the Justices, in September, refused to move up the schedule on the Maryland case so that it would be reviewed along with the Wisconsin case, which the Justices had agreed last June to review.

Instead of holding the Maryland case, though, the Justices agreed on Friday to accept it at the first opportunity, under current procedures, to do so.

Although the order accepting the case did not give a reason for that, one possible explanation is that the Justices may have looked at it in comparison to the Wisconsin case and decided that the ruling they are preparing would not necessarily fit the Maryland case, too

(…)

The Maryland case involves only the Sixth House District. For 20 years, it had regularly elected a Republican to that seat. But, in 2011, the state legislature drew lines that caused a shift of more than 90,000 voters’ areas in or out of the district, with twice as many Republicans moved out as Democrats that were moved in. The challengers – seven Republican voters who had lived in the old Sixth District — told lower courts that they had gathered strong evidence that state Democratic leaders drew the new lines with the specific aim of turning the Sixth into a Democratic district. Indeed, it has since elected a Democrat, Rep. John Delaney, in the 2012, 2014 and 2016 elections.

Another difference between the two cases that the Justices may have noticed, looking at them side by side to decide what to do with the Maryland case, is that each challenge to partisan gerrymandering relies upon a different constitutional theory.

The Wisconsin claim is that a partisan gerrymander harms the minority party by deviating statewide from “partisan symmetry” — that is, drawing lines that create districts that are out of balance with each other, with the majority party getting a statewide advantage over the minority party. It involves a rather complex mathematical formula based on “packing” minor party voters into fewer districts, or “cracking” districts dominated by minor party voters to spread them into majority party districts.

As the Maryland case developed, it has relied upon a simpler theory: when those drafting new legislative districts intentionally place voters in districts depending upon what party they have supported in the past, with the result that the disfavored party’s followers have their votes “diluted.” The federal courts are very familiar with vote dilution claims, after years of dealing with efforts to reduce the election influence of voters of minority races. The dilution theory, when applied to a partisan gerrymander claim, seeks to show that voters have been retaliated against because of their political views, said to be a violation of the First Amendment.

For decades, the Supreme Court has been unwilling to rule on the constitutionality of partisan gerrymandering, because the Justices have not found a workable theory for judging when there has been too much partisanship – especially since drawing new district maps every ten years is always infused with politics and partisan aspirations.

Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who has held an influential vote in this field of the law, has indicated in the past that he might find favor with an argument based upon the First Amendment rights of voters to express themselves in the way they vote.

The Maryland case probably will not come up for a hearing before the Justices earlier than next March. The Justices have the option of holding off on deciding the Wisconsin case until after that, but also the option of going ahead to decide it on its own, and then examine the Maryland case as a potential sequel.

And election law expert Rick Hasen speculates on why the Court may have chosen to take the case:

One thing it might mean is that Gill does not resolve the question of partisan gerrymandering but the Court (i.e., Justice Kennedy) wants things resolved this term. For instance, if the Court rejected something on standing or procedural grounds about Gill, this presents another opportunity to take a pass at the case. Then again, there’s a pending North Carolina case which is about the strongest indication of pure partisan intent as the Court is likely to ever see. Legislative leaders in North Carolina admitted they were acting for pure partisan purposes (in order to forestall a claim of racial gerrymandering). The NC case was put on hold after Gill, though that one too could have been set for argument.

It could also be that Gill finds partisan gerrymandering claims justiciable, but leaves certain issues open, issues which the Court then must resolve in Benisek.

But really, when reporters reached out to me last week to ask why the case was relisted, my answer was “who knows?” I stand by that answer.

The reasons speculated on by Denniston and Hasan for why the Court took this second case are all plausible, and we won’t know for sure until the Court hands down the decisions in these cases, or perhaps when this new case is argued before the Court early next year. As they both discuss, the issues in both cases are quite dissimilar so it doesn’t appear as though the outcome in one case is dependent in some way on how the Court rules in the other, although it’s possible that at least four of the Justices believe otherwise. In addition to those that they discuss, it could be that a majority of the Court in the Wisconsin case may believe that there is something about both cases that make them more similar that we’re recognizing, or perhaps the Court’s deliberations in that case have reached a point where they are looking at issuing a broader and more far-reaching opinion than the facts and questions of law at issue in the Wisconsin case allow them to do. If that’s the case, then it could mean that the Court is siding with the Plaintiffs in the Wisconsin case and that we could see an outcome that puts some limits on the ability of state legislatures to take partisanship into account when drawing district lines.

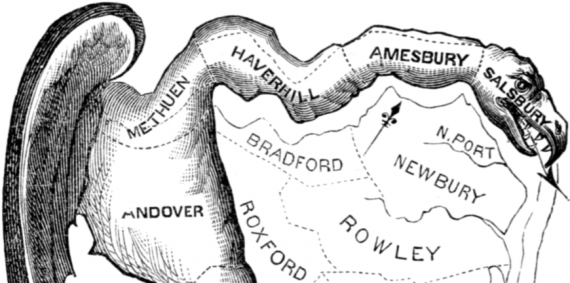

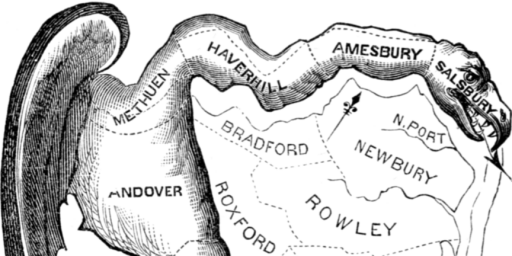

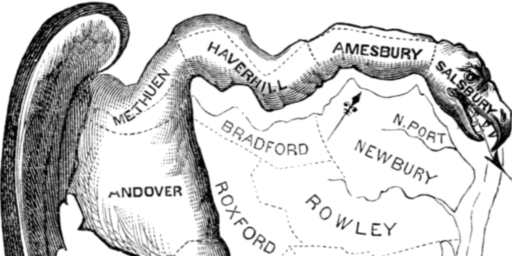

As I noted in my posts when the Supreme Court accepted the Wisconsin case for review, and again in October when the Court heard oral argument, I am somewhat skeptical of the arguments that were being raised in the Wisconsin case. The Constitution gives the states broad authority in drawing district lines for state legislative and Congressional districts. While it’s true that this authority has been limited to a significant degree by things such as the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, the Voting Rights Act, and the Supreme Court’s decision in Baker v. Carr and its progeny, the argument that the Constitution allows the authority of the state legislatures to be disrupted by the mathematical formulas used in the Wisconson case or the unique First Amendment argument being made in the Maryland case. Additionally, it’s worth noting that drawing district lines based on political considerations is hardly a new thing. The very name “Gerrymandering” comes from Elbridge Gerry, who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation and who was among the leading Anti-Federalists opposed to ratification of the Constitution even though he was one of the delegates in the Massachusetts delegation at the 1787 Convention. He also served as Vice-President under James Madison and as Governor of Massachusetts. It was during his time as Governor that the redistricting that came to bear his name occurred. While it was politically controversial at the time, there was never a serious legal argument from any of Founding Fathers who were alive at the time that what the state legislature had done in that case was or should be unconstitutional.

That being said, there is certainly a strong policy argument for the idea that partisanship should not play as decisive a role in redistricting as it does today, many of which have been raised here at Outside the Beltway by Steven Taylor. (See here, here, and here, for example.) Additionally, it’s clear that political Gerrymandering helps to contribute to the political polarization that makes it difficult if not impossible for anything to get done on Capitol Hill due to the fact that it favors candidates who can appeal to the most extreme and politically active factions of their political party and, as a result, are less subject to being influenced by their party leadership on even routine matters like budget votes or raising the debt ceiling, both of which have led to actual and threatened government shutdowns and had a significant negative impact on financial markets. That being said, I am loathed to see the Courts put their thumb on the scale with regard to an issue that the Constitution clearly seems to leave to the political process. We’ll have to wait to see just how the Supreme Court handles this.

As noted, the case has yet to be set for oral argument and has not even been assigned a briefing schedule yet (this won’t happen until a date for oral argument is selected most likely), but you can follow the case at the SCOTUSblog case information page, which at the moment includes links to the ruling of the three-judge panel from the U.S. District Court in Maryland as well as the briefs supporting and opposing the petition for Supreme Court review.

I wouldn’t pretend to understand what the Court is trying to do here. I am pretty sure that if John Roberts continues to pretend to not understand statistically based analysis, no good will come of this.

Each state should select a geographic unit of some kind (such as townships) and be permitted to bisect one less of them than exist legislative seats.

If state has 2 legislative seats, bisecting one unit is allowable; 12 seats, bisecting 11 is allowable, etc.