Supreme Court To Decide Meaning Of “One Person, One Vote”

The Supreme Court accepted a case that will require the Justices to decide just what it meant when it established the "one person, one vote" rule for drawing legislative districts.

The Supreme Court didn’t hand down decisions in any of its blockbuster cases today, meaning that it will be a very eventful June at the nation’s highest court, but they did accept a case for review that could have interesting implications for elections and the political system going forward:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Tuesday agreed to hear a case that will answer a long-contested question about a bedrock principle of the American political system: the meaning of “one person one vote.”

The court has never resolved whether that means that voting districts should have the same number of people, or the same number of eligible voters. The difference matters in places with large numbers of people who cannot vote legally, including immigrants who are here legally but are not citizens; unauthorized immigrants; children; and prisoners.

The new case, Evenwel v. Abbott, No. 14-940, is a challenge to voting districts for the Texas Senate brought by two voters, Sue Evenwel and Edward Pfenninger. They are represented by the Project on Fair Representation, the small conservative advocacy group that has mounted earlier challenges to affirmative action and to a central part of the Voting Rights Act.

“There are voters or potential voters in Texas whose Senate votes are worth approximately one and one-half times that of appellants,” the challengers’ brief said.

In a statement issued after the Supreme Court accepted their case, Ms. Evenwel and Mr. Pfenninger said they “hoped that the outcome of our lawsuit will compel Texas to equalize the number of eligible voters in each district.”

A 1964 Supreme Court decision, Reynolds v. Sims, ruled that voting districts must contain very close to the same number of people. But the court did not say which people count.

Almost all state and local governments draw districts based on total population. If people who were ineligible to vote were evenly distributed, the difference between counting all people or counting only eligible voters would not matter. But demographic patterns vary widely.

If the challengers succeed, the practical consequences would be enormous,Joseph R. Fishkin, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin wrote in 2012 in The Yale Law Journal.

It would, he said, “shift power markedly at every level, away from cities and neighborhoods with many immigrants and many children and toward the older, whiter, more exclusively native-born areas in which a higher proportion of the total population consists of eligible voters.”

Federal appeals courts have uniformly ruled that counting everyone is permissible, and one court has indicated that it is required.

In the process, though, several judges have acknowledged that the Supreme Court’s decisions provide support for both approaches. The federal appeals court in New Orleans said the issue “presents a close question,” partly because the Supreme Court had been “somewhat evasive in regard to which population must be equalized.”

Judge Alex Kozinski, in a partial dissent from a decision of the federal appeals court in San Francisco, said there were respectable arguments on both sides.

On one theory, he said, counting everyone ensures “representational equality,” with elected officials tending to the interests of the same number of people, whether they are voters or not.

On the other hand, he said, counting only eligible voters vindicates the principle that voters “hold the ultimate political power in our democracy.” He concluded that the Supreme Court’s decisions generally supported the second view.

Even if counting only adult citizens is the correct approach, there are practical obstacles. “A constitutional rule requiring equal numbers of citizens would necessitate a different kind of census than the one currently conducted,” Nathaniel Persily, a law professor at Stanford, wrote in 2011 in the Cardozo Law Review.

For now, he said, “the only relevant data available from the census gives ballpark figures, at best, and misleading and confusing estimates at worst.”

Lyle Denniston goes into more detail about what the Court will be asked to do here:

The usual choice considered by legislatures is to make districts more or less equal by dividing up shares of the state’s total population, or, as an alternative, to draw lines based upon some measure of the voting members of the population — such as the numbers actually registered to vote.

Two Texas voters, who wound up in state senate districts where they say their votes will count less than the votes in another district even though each of those districts has about the same total number of people, argued that this contradicts the “one-person, one-vote” guarantee of voter equality. Their votes would have counted equally, they contended, if the legislature instead had used voting-age population as the measure.

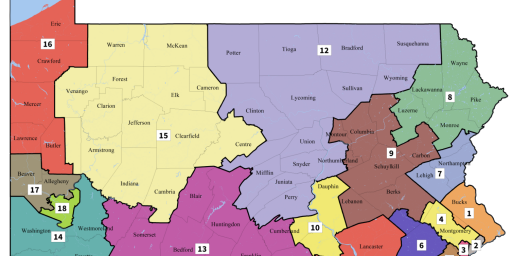

The voters, Sue Evenwel, who lives in Titus County in Senate District 1, and Edward Pfenninger, who lives in Montgomery County in District 4, said their votes were diluted because of the disparity between the two measures as applied to those districts, where more of the people vote proportionally. Both districts are rural. Other, more urban districts have proportionally fewer registered voters, so the redistricting plan based on actual population is said to give those who do vote more weight — that is, fewer of them can control the outcome.

“A statewide districting plan that distributes voters or potential voters in a grossly uneven way,” the two voters told the Court, “is patently unconstitutional under Reynolds v. Sims and its progeny.”

The voters do not argue that legislatures should be forbidden ever to use total population as the districting measure, but only when it results in the kind of disparity, compared to a plan based on voters’ numbers, that resulted in Texas.

At the theoretical core of this dispute is the theory of representation that a legislature should follow. Texas, supported by the lower court in the new cases, argued that this is a question of how to define democracy, a question that it said should be left to the people’s elected representatives, and not decided by the courts. The state also contended that the Supreme Court had said explicitly in a 1966 decision (Burns v. Richardson) that the choice of population measure was a matter for legislatures.

And Election Law Blog’s Rick Hasen, meanwhile, that the Court granting review here isn’t entirely surprising:

The Supreme Court’s decision today to decide what “one person, one vote” actually means is not all that surprising, at least to many of us. In all the years since the Court recognized that election districts must have equal populations, the Court never squarely resolved what the baseline ought to be for determining “equality” — must districts have equal numbers of residents or equal numbers of eligible voters (which would exclude the young, non-citizens, felons unable to vote)? In 1966, in the earliest days of the reapportionment revolution, the Court did hold that states could choose between equalizing population or eligible voters (Burns v. Richardson, 384 U.S. 73 (1966)). But a lot has happened in the maturation of the law in the ensuing 50 years; in general, the Court has placed greater emphasis on the use of more concrete, precise standards.

Moreover, there is something odd about such a basic constitutional standard under the Equal Protection Clause as the principle of political equality that’s reflected in the “one person, one vote” standard being so ill-defined that states are free to choose whether it’s persons or voters that matter for purposes of equality. Few constitutional standards work that way. In practice, most states have used residents, not voters, for the baseline, but the doctrine leaves open the possibility that states could use other baselines. And as long as the baseline remains constitutionally undefined, states can manipulate the districting system by choosing one baseline over another in order to achieve various partisan or political ends. The difference can be significant, especially in areas of the country — such as Texas, where this case comes from — with large numbers of non-citizen residents.

As Hasen goes on to note, perhaps the best thing that could result from this case is that the Court sets down some kind of clear standard of what “one person, one vote” means when it comes to drawing up legislative districts. What standard it chooses, though, could have a significant impact on politics both at the state and the federal level for years to come. A standard that is based on something as broad as total population, for example, would mean that areas with high numbers of people who aren’t eligible to vote for one reason or another would end up with political power disproportionate to their population. This is how things presently work in Texas with Senate districts, and it is the reason for the case that is now before the Court. Conversely, a standard that stated that seats should be apportioned based on the total number of citizens, or the total number of eligible voters, would tend to balance out that political power and potentially give voters in rural districts slightly more political power in some situations. Even in a solidly red state like Texas, this could have a significant impact on the political system. In any case, Hasan has a point when he argues that there is at least some value in the fact that the Court seems to finally be ready to establish a standard to a rule that it left essentially open ended when the “open person, one vote” default rule for drawing political boundaries was first established.

In any case, whatever the Court decides here is likely to have widespread implications not just inside Texas, but well beyond there. Ultimately, it is likely to spark a whole new round of litigation over Congressional redistricting after the 2020 Census, which may be one reason why the Court would be likely to establish a clear rule in its decision rather than a standard that would just be open to further litigation. Legislators will need to begin drawing new district boundaries as soon as the Census results are available, and Judges who will be asked to review those districts in the inevitable lawsuits are going to need a clear guideline. Otherwise, the Court will just be dealing with this all over again.

Given the makeup of this court, and Roberts’ hostility to any schemes protective of minority voting rights-I have a bad feeling about this.

The sooner Hillary starts appointing Supreme Court justices, the better.

I frankly do not see how this appeal has merit or could be considered “close.” The Constitution gave the right to vote through the intermediary of the States, all of the oldest of which had majorities which were not eligible to vote at one time.

Furthermore, there is no individual right to vote in any election, just simply the right to vote when extended cannot be encumbered on the basis of race, gender or other protected class. What is the class that is being treated unequally here? People living in areas with higher voter turnout?

@PD Shaw:

What is the class that is being treated unequally here? People living in areas with higher voter turnout?

Presumably, citizens.

It looks to me as though Texas is trying to take another bite at pushing the federal government to enforce the border. I’m a bit puzzled by the case having advanced this far. Clearly, some judges somewhere have thought it had merit.

Hobby Lobby = 1 Person.

What’s the question?

@Dave Schuler: The odd thing here is that the Texas Republican party that controls the state is well aware of how best to game the electoral system to maintain control, and they didn’t try to count only eligible voters. The lawsuit appears to be arguing that it is mandatory to do so, even though there does not appear to be a single state that is doing it per the Yale Law Journal article.

I suspect the lawsuit is actually about something else, like establishing an individual’s right to sue the state when a citizen’s vote is being diluted by lax or non-enforcement of voting requirements.

@stonetools: I agree. This court scares me. They would undo much of the 20th century if they got the chance.

Conservatives again prove they cannot win with their policy ideas, so instead they work tirelessly to dilute the power of their enemies.

Since this is a conservative activist group in Texas, it could be to dilute the number of overwhelmingly Democratic Districts that have fewer eligible voters. How many people live in Shelia Jackson Lee’s district but are not eligible voters and not citizens. If her district required the same number of eligible voters and the Republican districts, there is a chance that she would not be re-elected.

I can’t believe that conservatives would ignore the rights of unborn babies to be counted as part of their voting district.

But in all seriousness, it’s interesting that it is basically required at this point to be counted one way or the other. When, in fact, one might prefer to exclude certain groups (perhaps felons) but include others (perhaps children). But I suppose that would require a level of census accuracy beyond what we apparently have, since one of the articles above suggests that even knowing the number of eligible voters is too difficult.

Perhaps illegal immigrants can be counted as 3/5ths of a person.

I have little doubt this is just a typical Republican ploy to try to steal more elections, and even less doubt that this court will simply split along party lines. However the Repubs victory in this may eventually backfire. Remember, the solidly Republican House of Reps cumulatively received fewer votes than their Democratic opponents. And of course the Supremes gave the election to George W. who received fewer votes than Al Gore.

Of course this Supreme Court will seek to apply it only in circumstances that favor their patrons (vis a vis the ridiculous “sets no precedent” comment on Bush v. Gore) but eventually a Democratic president will be able to appoint some justices and the precedent will kick in. Truly representative voting. And the Repubs will be out on their a**.

@Rob Prather: “I agree. This court scares me. They would undo much of the 20th century if they got the chance.”

You are easily scared and manipulated.

@PD Shaw:

Er, No, he is spot on:

And, just to anticipate an argument, just because the SCOTUS conservatives don’t use the phrase doesn’t mean that they are not acting in accordance with the doctrine. Conservatives know that “rolling back to clock to 1932” isn’t a idea with majority support, so they naturally want to engineer the rollback by stealth.

Frankly, I admire the astuteness of approach. Conservatives, unlike liberals, understand the strategic importance of acting in a clandestine manner ito accomplish certain goals.

I am sure the Tea Party will be the first to cry out, “NO TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION!!!”

Doug: “As Hasen goes on to note, perhaps the best thing that could result from this case is that the Court sets down some kind of clear standard of what “one person, one vote” means when it comes to drawing up legislative districts.”

No, because the most likely outcome from this court is something which defines that to mean ‘whatever benefits the GOP at this time’.

The SCOTUS is by far the biggest issue in the upcoming Presidential election.

Marriage equality, economic inequality, foreign policy, the environment…all important.

Keeping the SCOTUS from becoming even more retarded…critical.

I wonder if the Supremes will apply this to people disenfranchised due to being in prison. After all, most prisons are in rural areas, and the prisoners are generally not. If only citizens eligible to vote counted, then communities with prisons would see their influence drop.

I’d love to see the Venn diagram of those who think that this is a good idea and those who favor getting rid of the electoral college and the US going to a nationwide popular vote.

The right to have “your vote count” in a district, where it can dilute the strength of of non-voting population certainly syncs up with wanting to have “your vote count” in a nationwide election where it dilutes the power of smaller rural states…. right?

It’s about fairness, not gerrymandering manipulation….right?

/

I’d actually be willing to consider some type of change if it was tied to getting rid of the electoral college and towards a popular vote.

I’m wondering, in the event that the court decides that some more restrictive means of counting is required to determine the size of a state senate district, would logic dictate that it would also apply to apportionment of Representatives in Congress among the states?

@PD Shaw: Care to expand on that? I don’t see the connection.

@Tom M: I’ve been late to this, and it is largely unrelated to this post, but I would love to see us go to a national popular vote.

so we’re actually counting “illegals” as part of the population now? now just suppose a certain area was prone to having a high populace of convicted felons- who can’t vote- same deal?

@Tony W: so the majority of the congress/senate proves that now? it’s called “buyers remorse”- they realize they were duped and obama was not what he should have been.

@Gustopher:

Remember, it was slave holding Southerns who wanted slaves count as whole persons and non-slave holding northerners who did not want them to count for representation purposes at all. The 3/5 was a compromise that did slightly dilute the political power of the northern states.

What the conservative activist in Texas are arguing is similar to what northerners were arguing when the constitution was written. Why should someone who repressents a district with large numbers of aliens (legal and illegal) get to be elected with fewer votes than a representative of a district with few aliens?

@bill:

To the extent they were elected fairly and without cynical Gerrymandering and polling place interference, yes. Unfortunately we are nowhere near one-person/one-vote, and if we were Congress would look much different.