Supreme Court Upholds Campaign Finance Limitations In Judicial Elections

In a marked departure from recent cases, the Supreme Court rules that states can impose significant restriction on solicitation of campaign contributions in judicial elections.

In an opinion that both went against recent precedent in the area of campaign finance regulation, and included a rather unusual ideological pairing in the majority, the Supreme Court ruled today that restrictions that prevent candidates in judicial elections from soliciting donations do not violate the First Amendment:

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court ruled Wednesday that states may limit candidates for elected state and local judgeships from making a personal appeal for campaign contributions.

The justices’ 5-4 ruling means in 30 states that elect state and local judges, restrictions on judicial candidates and their campaign solicitations can remain in place. In all, 39 states hold elections for judges and some allow personal appeals.

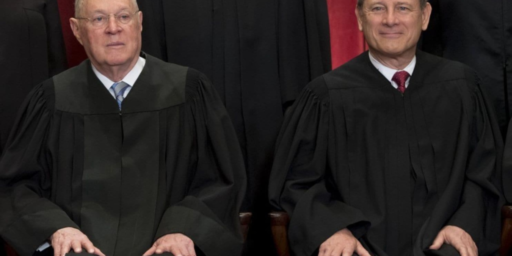

Chief Justice John Roberts said in his majority opinion that laws barring judicial candidates from personally asking for campaign cash do not run afoul of First Amendment free speech rights.

“Judges are not politicians, even when they come to the bench by way of the ballot,” Roberts said. “A state may assure its people that judges will apply the law without fear or favor — and without having personally asked anyone for money.”

The court’s four liberal justices joined Roberts.

The ruling took note of concerns that lawyers in particular might have a hard time refusing to contribute when a judge personally asks for campaign cash.

The case of Lanell Williams-Yulee of Tampa, Florida, arose after Williams-Yulee signed a mass-mailing asking for money for her campaign for a local judgeship, and also posted the letter on her website. The appeal didn’t yield a penny, but Williams-Yulee received a public reprimand for violating a Florida Bar rule that bans candidates for elected judgeships from personally soliciting donations.

In dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia called the Florida rule a “wildly disproportionate restriction upon speech” that should be struck down under the First Amendment. Scalia said the electoral setting “calls for all the more vigilance” in protecting free speech rights.

The justices had previously struck down limits on what judicial candidates can say during campaigns. In 2002, the court struck down rules that were aimed at fostering impartiality among judges and barred candidates for elected judgeships from speaking out on controversial issues.

But in 2009, the court held in a case from West Virginia that elected judges could be forced to step aside from ruling on cases when large campaign contributions from interested parties create the appearance of bias.’

Lyle Denniston summarizes the opinion:

In a quite modest retreat from the Supreme Court’s full support for the free and massive flow of money into American politics, the Justices split five to four on Wednesday in allowing states to bar candidates for judgeships from personally asking for campaign donations. Although the majority left wide options for judicial candidates to obtain funds near election time, and even to thank the donors, the ruling drew deeply pained protests from four dissenters that the Court was seriously undercutting the First Amendment in the campaign realm.

What clearly made the difference, in this break from a string of First Amendment rulings protecting big money in politics, was that this was about judicial elections and the majority was worried that asking directly for money by a would-be judge was a serious threat to judicial integrity. By assigning the main opinion to himself, as the nation’s highest-ranking judge, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., gave the ruling something of the stature of a national judicial policy declaration.

At issue in the case of Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar was a state ethical rule that no candidate for a state judicial office may personally ask anyone for a campaign contribution — whether the person contacted was a lawyer, a friend, or even a family member. That, the Chief Justice wrote, is sufficiently related to a state’s interest in impartial courts that it is permissible under the First Amendment.

“When the state adopts a narrowly tailored restriction like the one at issue here,” Roberts’s opinion said, the right of judicial candidates to speak and the interest of the state in protecting the public reputation of the judiciary “do not conflict. A state’s decision to elect judges does not compel it to compromise public confidence in their integrity.”

The opinion professed to take no position on the good or bad of choosing judges by popular elections, noting that the question “has sparked disagreement for more than 200 years.” But the outcome of the case was a reinforcement of the state’s limited power, when it does choose judicial elections, to try to dispel the notion that judges are just like other politicians with tin cups in hand.

The decision made clear, through the support of four Justices who were part of the majority and four Justices who were in dissent, that any restriction on what candidates for elective office — including those seeking judgeships — may say in reaching out to voters must pass the most demanding constitutional test (“strict scrutiny”). Only Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg would not go along with that standard, arguing that states should have more leeway in putting limits on the financing of judicial elections.

And election law expert Rick Hasen has these observations:

Chief Justice Roberts’ opinion for the Court, with the four liberals, over the dissent of the four more conservative Justices, is unusual—Roberts usually does not side with the liberals in these cases over the objections of the conservative Justices. So what motivated things? It comes from the very beginning of the case: Chief Justice Roberts says that judicial elections are different, and that therefore the First Amendment analysis is different. This is a huge change in Supreme Court doctrine, where in cases like Minnesota Republican Party v. White the Court did not accept such differences as a basis for restricting the speech of judicial candidates. This is an acceptance of Justice Ginsburg’s White, dissent in which she rejected the “unilocular” an election is an election.

(…)

The state’s interest which lets the law survive strict scrutiny is public confidence in the judiciary. This makes me a bit queasy—because in other areas where the Court has purported to uphold laws to promote public confidence (think voter id laws, Shaw v. Reno expressive harms in the racial gerrymandering context, and the appearance of corruption in campaign finance law), the social science showing that these laws promote public confidence is shaky to non-existent. Nate Persily and others have done important work on this. And Jim Gibson’s important book shows that in some ways judicial elections, even nasty partisan ones, can help with public confidence. Justice Scalia in his dissent comes down hard on this interest.

This is also a big, big win for Justice O’Connor, who has been pushing issues of judicial integrity and the need to allow for different rules in the judicial elections context. This is a very big deal which will likely make it much, much easier to uphold a host of different campaign finance and speech rules in the judicial elections context. The Chief’s discussion of how “narrow tailoring” under strict scrutiny is not “perfect tailoring” will help a great deal in this regard.

The big question will be whether spending limits and limits on super pacs in judicial elections can now pass constitutional muster. There’s the hint of that in Caperton (though the Chief Justice dissented there and Justice Kennedy was on the other side there). Certainly the door is open now for respectable arguments on this side.

To an outside observer, the Court’s decision here likely seems like a bit of an oddity given recent rulings in cases such as Citizens United v FEC, SpeechNOW v. FEC, and McCutcheon v. FEC, and others where the Court has put significant limits on the ability of federal and state authorities to regulate political speech connected to political campaigns, including fundraising and expenditures by entities unaffiliated with any political campaign or party. Taking the rules that have been set forth in those cases literally, one would think that a rule such as the one here, which prohibits candidates for judicial elections from actively soliciting for donations, would be a clear violation of the First Amendment. When you read those cases, however, what becomes clear is that the Court is applying a balancing test that measures the free speech rights of candidates, parties, and outside groups against the interests being asserted in defense of the laws and regulations in question. For the most part, the court has found that the interests asserted were not sufficient to justify the outright bans or significant limits on speech that the laws represented. In this case, though, it’s clear that what the court is saying is that there is a difference between elections for political offices and judicial elections that justifies more significant restrictions in the latter that would not be permissible in the context of a race for political office.

While some may dismiss this as a distinction without a difference, it strikes me that the Court is correct to recognize it given the significant differences between what it means to be a judge and what it means to be an elected official. Even when they are elected, judges are not supposed to be advancing a particular political ideology or policy agenda. At the trial level, their job is to apply the law to the facts presented to them and, at the appellate level, their job is supposed to be to properly interpret the law. There’s no room in either of those roles for partisan politics, or at least their shouldn’t be, and even though it’s often done with a wink and a nod, both the states and the Federal Constitution takes steps that are intended to protect judges from the whims of politics and popular will. Additionally, there are real concerns about corruption that are raised by the prospect of judges soliciting donations, usually from lawyers, in an election, with the obvious implication being that a donation could mean favorable treatment in court and the lack of a donation could mean otherwise. In an ideal world, I would suggest that there should not be judicial elections at all, but as long as there are it is entirely reasonable for the states to regulate them in a manner designed to ensure that the process discouraged such practices. Indeed, in the 39 states where at least some judicial seats are filled by election, 30 states have rules that ban candidates from soliciting donations, and all of them have more significant restrictions on campaigning by judicial candidates than those for candidates for regular political offices. Today, the Court recognized the difference between judicial and political offices and ruled, correctly I believe, that those regulations are entirely within the state’s authority.

Going forward, I would not expect that we will see this decision having any real impact on other campaign finance cases that will come before the Court. The distinction that the court makes here between judicial elections and elections for other political offices is clear enough that it seems unlikely that we’re seeing any kind of sea change in the Court’s view on that issue. As Hasan notes above, though, what this case does signal is that the Court could start to look differently on other methods of regulating judicial elections. Given that, it’s likely we’ll see more cases making their way through the courts based on what the court decided here today.

Here’s the opinion:

This was about Robert’s sense of love for the judiciary, IMO.

A judge asking a lawyer for a donation in the middle of a case is just downright silly – it’s blatant corruption. But a politician asking for a donation from a company prior to a vote he’s about to make concerning the company’s business sector – now that’s just free speech.

“…some may dismiss this as a distinction without a difference..”

Those people would be right.

This, exactly.

Justice Scalia is growing more and more worried about his mortality and the fact that a Democrat is going to pick his successor.

I’ve gotten much more curmudgeonly about the First Amendment. I think SCOTUS is completely wrong in certain areas:

1) Begging. I don’t consider this a free speech issue. They’re asking for money, treat it as commercial speech and regulate the hell out of it. Maybe if the Justices had to run a gauntlet of beggars every day going to and from work they’d understand this better.

2) Threats of grievious bodily harm transmitted over the internet. ‘Nuff said.

3) Citizens Limited. Also, enough said.

Once lobbyists have bought the laws they want from the legislature, it’s not a problem for them to be adjudicated without fear or favor.

What do you mean I can’t buy my Judges anymore???? That’s just Un-American!!!!

He’s noticed the political winds are all a-tumble. For sure it’s a nor’easter comin’ in, but there’s the faintest hint of a sou’wester that might turn this into a devastating ‘nader. (Only if the sou’wester nominates a respectable cumulonimbus with a broad, uh, expanse, anyway.)

Dude’s not ignorant of court history and legacies as they oft develop. He’s a smart guy. It’s not like he singlehandedly saved Obamacare because he had judicial principles. I give him more credit than principles.

@OzarkHillbilly: If I understand this correctly, you can still buy a judge. It’s just that the judge can’t ask you to buy him.

This is just the exception that proves the rule. The rule is that this court will rule however it feels will benefit Republicans. So this exception has nothing to do with “money is speech” or any other first amendment twaddle. It’s simply that Roberts doesn’t feel that this benefits Republicans any more than Democrats and he can’t stand to see his own house soiled. Doug, you can try to impart logic all you want but ever since the Bush/Gore ruling, where the court literally said not to take it as a precedent. To me anyway, the clause they were leaving out was “…because the next time a similar ruling may benefit a Democrat and we can’t have that”

@gVOR08:

Yes, the judge can sit in the red window and give a wink and a smile, but can’t invite you in.

“Judges are not politicians, even when they come to the bench by way of the ballot,” Roberts said. Bwah ha ha ha ha! Being a Supreme Court Justice means never having to have self awareness.

It is mind boggling to me that Justice Roberts (and Doug) can say with a straight face that the law is that politicians can be bought ( including and up to the President of the United States), but judges cannot be. This is such a classic example of pretzel logic that it should be cited in the dictionary definition of the term. Oxford, take a look at this.

Well, I’ll see if I can repair my sophistry meter, because it blew up when I read the above article.

@grumpy realist: True to form, the WALL STREET JOURNAL is doing a journalistic pout in today’s issue.