Supreme Court Rules Against Military Tribunals; Geneva Applies to Al Qaeda (Updated)

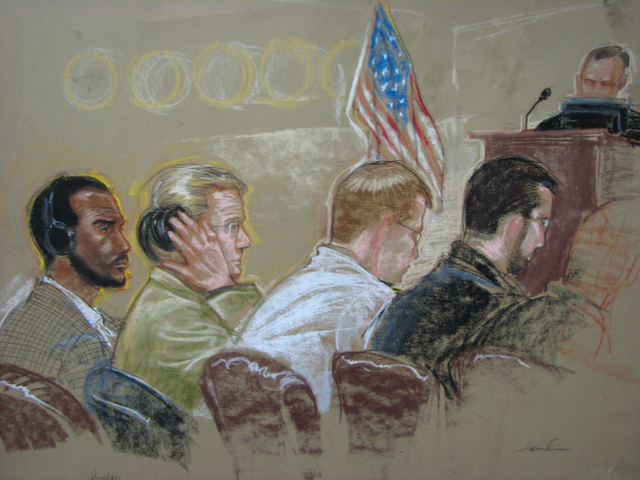

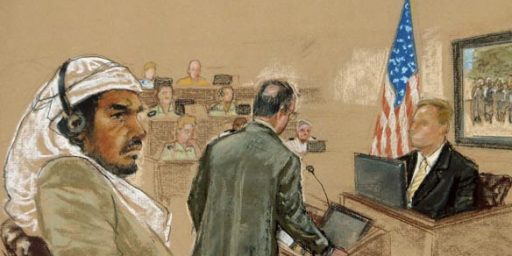

The Supreme Court ruled that Ahmed Salim Hamdan was being improperly held at Guantanamo Bay and apparently held that President Bush does not have the power to try those he deems “enemy combatants” in military tribunals.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that the Bush administration did not have the legal authority to go forward with military tribunals for detainees at the Guantanamo Bay military base in Cuba. The 5-3 ruling means officials will either have to come up with new procedures to prosecute at least 10 so-called enemy combatants awaiting trial, or release them from U.S. military custody. The case was a major test of President Bush’s authority as commander in chief in a wartime setting. Bush has aggressively asserted the power of the government to capture, detain, and prosecute suspected terrorists in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.

The high court was ruling on the case of Ahmed Salim Hamdan, a Yemeni native captured in Afghanistan in 2001, shortly after the September 11 attacks. He is accused of conspiracy, which his lawyers say is not an internationally approved charge. His lawyers argued that President Bush exceeded his authority by setting up military commissions to try terrorist suspects, whom the administration terms “enemy combatants,” rather than prisoners of war. The term means the suspects do not have the rights traditonally afforded prisoners of war, as outlined in the Geneva Conventions.

Three issues were before the high court: whether the planned tribunals are a proper exercise of presidential authority; whether detainees facing prosecution have the right to challenge the procedures of those tribunals and their detentions; and whether the Supreme Court even has the jurisdiction to hear such appeals.

[…]

Chief Justice John Roberts did not participate in the Hamdan case. He had ruled against the government last year when the case was argued in a lower federal appeals court.

More once I see the ruling itself. Obviously, not much to go on from just this report.

While it has long seemed obvious that the president did not have the authority to term United States citizens “enemy combatants” and thereby deprive them of their constitutional rights, the court has a long history of deferring to wartime presidents in their role as commander-in-chief. The idea that enemies captured fighting American soldiers on the battlefield have due process rights is frankly idiotic; one suspects the ruling is much more narrow than described by CNN.

UPDATE: Lyle Denniston writes,

The Court expressly declared that it was not questioning the government’s power to hold Salim Ahmed Hamdan “for the duration of active hostilities” to prevent harm to innocent civilians. But, it said, “in undertaking to try Hamdan and subject him to criminal punishment, the Executive is bound to comply with the Rule of Law that prevails in this jurisdiction.” [emphasis mine-JJ]

That quotation was from the main opinion, written by Justice John Paul Stevens. That opinion was supported in full by Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and David H. Souter. Justice Anthony M. Kennedy wrote separately, in an opinion partly joined by Justices Breyer, Ginsburg and Souter. Kennedy’s opinion did not support all of Stevens’ discussion of the Geneva Convention, but he did find that the commissions were not authorized by military law or that Convention. Kennedy expressed no view, for example, on whether Hamdan could be charged with conspiracy or whether the accused has a right under the Convention to be present in all commission proceedings. Since he is not in dissent on those points, however, the Stevens opinion would seem to be controlling as to those points because not overcome by the three dissenting votes.

That makes much more sense. I’ll be interested in reading the opinions and, especially, Scalia’s dissent.

Howard Bashman provides links to oral arguments transcripts [PDF] and background information, including the DC Circuit opinion.

Lawhawk is reserving comment until the opinion is posted here. As of this writing, it’s not yet up. [UPDATE: It is now. 185 pages, though!]

UPDATE: Allahpundit, John Stevenson, and Michelle Malkin have huge roundups. The former hopes this will be John Paul Stevens’ last opinion on the Court.

Marty Lederman has the syllabus and thinks this will have explosive consequences:

[T]he Court held that Common Article 3 of Geneva aplies as a matter of treaty obligation to the conflict against Al Qaeda. That is the HUGE part of today’s ruling. The commissions are the least of it. This basically resolves the debate about interrogation techniques, because Common Article 3 provides that detained persons “shall in all circumstances be treated humanely,” and that “[t]o this end,” certain specified acts “are and shall remain prohibited at any time and in any place whatsoever”—including “cruel treatment and torture,” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.” This standard, not limited to the restrictions of the due process clause, is much more restrictive than even the McCain Amendment. See my further discussion here.

This almost certainly means that the CIA’s interrogation regime is unlawful, and indeed, that many techniques the Administation has been using, such as waterboarding and hypothermia (and others) violate the War Crimes Act (because violations of Common Article 3 are deemed war crimes).

If I’m right about this, it’s enormously significant

Oak Leaf is apoplectic:

This morning, the United States of America signed the instrument of surrender with al Queda and all affiliated terror organizations. The signatories representing the United States were Anthony Kennedy, Steven Bryer, John Paul Stevens, Ruth Ginsburg and David Souter.

The reason for this unconditional surrender was that while the Supreme Court Justices “support the troops” and particpate in drives to send old magazines to soldiers, they do not “Trust the Troops.”

In addition, this was a total rebuke of Chief Justice John Roberts whose lower court ruling was overturned. [emphasis original]

The last point is quite interesting; it hadn’t occured to me.

While I agree with the administration (and thus disagree with the Court’s majority here) that the Geneva Conventions are largely inapplicable to non-uniformed fighters like terrorists, the idea that this constitutes a “surrender” is over-the-top. By and large, we’ve acted as if Geneva did apply while saying that it didn’t. And we’ve applied Geneva to the guerrillas in Iraq without any obvious negative consequence.

UPDATE: A PDF of the decision is now up. It’s 185 pages.

Scalia’s dissent begins on p. 103. I’ll begin there, letting others dissect Stevens’ opinion. Scalia’s thrust is that SCOTUS lacks the jurisdiction to intervene here and, even if it didn’t, it is damned foolish to do so.

On December 30, 2005, Congress enacted the DetaineeTreatment Act (DTA). It unambiguously provides that, asof that date, “no court, justice, or judge” shall have juris-diction to consider the habeas application of a Guan-tanamo Bay detainee. Notwithstanding this plain direc-tive, the Court today concludes that, on what it calls thestatute’s most natural reading, every “court, justice, or judge” before whom such a habeas application was pend-ing on December 30 has jurisdiction to hear, consider, and render judgment on it. This conclusion is patently errone-ous. And even if it were not, the jurisdiction supposedlyretained should, in an exercise of sound equitable discre-tion, not be exercised.

[…]

An ancient and unbroken line of authority attests that statutes ousting jurisdiction unambiguously apply to casespending at their effective date.

A cursory scan of the remainder of Scalia’s dissent focuses on those narrow issues. Only tangentially is there any policy consideration given, as in this passage:

Here, apparently for the first time in history . . . a District Court enjoined ongoing military commission proceedings, which had been deemed “necessary” by the President “[t]o protect the UnitedStates and its citizens, and for the effective conduct of military operations and prevention of terrorist attacks.” Military Order of Nov. 13, 3 CFR §918(e). Such an order brings the Judicial Branch into direct conflict with the Executive in an area where the Executive’s competence is maximal and ours is virtually nonexistent.

Quite.

Justice Thomas’ dissent [pp. 127-] (joined by Scalia and, mostly, Alito) focuses on the public policy question of presidential authority. He cites a steady stream of precedent to the effect that,

When “the President acts pursuant to an express or implied authorization from Congress,” his actions are”‘supported by the strongest of presumptions and the widest latitude of judicial interpretation, and the burden of persuasion . . . rest[s] heavily upon any who might attack it.'”

[…]

Under this framework, the President’s decision to try Hamdan before a military commission for his involvement with al Qaeda is entitled to a heavy measure of deference. In the present conflict, Congress has authorized the Presi-dent “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001 . . . in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizationsor persons.”

UPDATE: Reading Stevens’ Majority Opinion now. The Detainee Treatment Act specifically takes away judicial authority over cases such as this. As Stevens quotes:

“‘(e) Except as provided in section 1005 of the De-tainee Treatment Act of 2005, no court, justice, orjudge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider—

“‘(1) an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien detained by the Depart-ment of Defense at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; or

“‘(2) any other action against the United States or its agents relating to any aspect of the detention bythe Department of Defense of an alien at GuantanamoBay, Cuba, who—

“‘(A) is currently in military custody; or

“‘(B) has been determined by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuitin accordance with the procedures set forth in section 1005(e) of the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 to have been properly detained as an enemy combatant.'” §1005(e), id., at 2741—2742.

Stevens’ claim that this might not have meant to apply to Hamden, who was already in custody because “the Act is silent” on that fact, is plainly absurd.

Hamdan objects to this theory on both constitutional and statutory grounds. Principal among his constitutionalarguments is that the Government’s preferred readingraises grave questions about Congress’ authority to im-pinge upon this Court’s appellate jurisdiction, particularly in habeas cases.

But, guess what? Congress has plenary power to delimit the scope the judiciary insofar as it does not impinge on those matters where the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction enumerated in Article III, Section 2. As the FindLaw summary notes, “[E]xcept for the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, which flows directly from the Constitution, two prerequisites to jurisdiction must be present: first, the Constitution must have given the courts the capacity to receive it, and, second, an act of Congress must have conferred it.” Just as surely, a specific Act of Congress saying the courts do not have power is the opposite of “vesting.”

Stevens’ later quoting of language from the floor debates in defense of a bizarre interpretation of the DTA is laughable. Indeed, Scalia rightly skewers him for it in his dissent.

Together, the UCMJ, the AUMF, and the DTA at most acknowledge a general Presidential authority to convene military commissions in circumstances where justified under the “Constitution and laws,” including the law of war. Absent a more specific congressional authorization, the task of this Court is, as it was in Quirin, to decide whether Hamdan’s military commission is so justified.

Interestingly, this permits a backdoor evasion of the ruling. Congress could, this afternoon if it wishes (assuming the Members could be rounded up) pass a statute authorizing these specific military commissions and stating that the Courts have no jurisdiction over them. [Update: Andrew Cochran agrees: The President and GOP leaders will propose a bill to override the decision and keep the terrorists in jail until they are securely transferred to host countries for permanent punishment. . . .The bill will pass easily and quickly. And if the Supremes invalidate that law, we’ll see another legislative response, and another, until they get it right. Just watch.”] [Update 2: President Bush apparently agrees, too.]

The most interesting part of Steven’s ruling is his invocation of the Law of War:

This high standard was met in Quirin; the violation there alleged was, by “universal agreement and practice” both in this country and internationally, recognized as an offense against the law of war. 317 U. S., at 30; see id., at 35—36 (“This precept of the law of war has been so recog-nized in practice both here and abroad, and has so gener-ally been accepted as valid by authorities on international law that we think it must be regarded as a rule or princi-ple of the law of war recognized by this Government by its enactment of the Fifteenth Article of War” (footnote omit-ted)). Although the picture arguably was less clear in Yamashita, compare 327 U. S., at 16 (stating that theprovisions of the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907, 36Stat. 2306, “plainly” required the defendant to control the troops under his command), with 327 U. S., at 35 (Mur-phy, J., dissenting), the disagreement between the major-ity and the dissenters in that case concerned whether the historic and textual evidence constituted clear precedent—not whether clear precedent was required to justify trialby law-of-war military commission.

At a minimum, the Government must make a substan-tial showing that the crime for which it seeks to try a defendant by military commission is acknowledged to be an offense against the law of war. That burden is far from satisfied here. The crime of “conspiracy” has rarely if ever been tried as such in this country by any law-of-war mili-tary commission not exercising some other form of juris-diction,35 and does not appear in either the Geneva Con-ventions or the Hague Conventions—the major treaties on the law of war.36

But, surely, that part of Quirin is mere dicta. It merely states that the law of war is a longstanding concept; it doesn’t require that charges brought against non-military combatants have to be codified in universal understanding. Besides which, as Stevens soon notes, the charge of conspiracy was brought in Quirin itself and not ruled down by the Court! Stevens takes the fact that the Quirin court made no mention of the conspiracy charge as evidence that they didn’t think it had merit!

And this must have been thrown in just to piss off Scalia:

Finally, international sources confirm that the crime charged here is not a recognized violation of the law of war.

So?

Elsewhere:

Steve Bainbridge: “Is ‘war’ the right metaphor for dealing with terror? Or should we accept that terror is really mainly a police/intelligence issue? If the latter is the right metaphor, this ruling makes more sense.” (And vice versa?)

Ann Althouse: “It is standard practice for the Court to read statutes that purport to cut back jurisdiction in a way that is defensive of the role of the judiciary.” (Otherwise known as ignoring the law when they don’t like it?)

Cigar Intelligence Agency: “That’s why you don’t take terrorists as prisoners and try to ‘bring them to justice’. You mete justice out to them where you find them, and arrange that meeting with Allah and the 72 virgins.” (Yup)

UPDATE: President Bush will ask Congress for a law allowing military tribunals for Gitmo detainees. My strong guess is it’ll pass, quickly.

________

Related:

Now that the Court has ruled I expect the President to follow the law. That does not mean he was doing anything wrong in the first place. Sometimes law is established just as it has been in this case. Two opposing parties work it through the courts until the law is interpreted and decided. Critics of Bush should keep that in mind before attacking him for his actions.

He’ll probably issue a “signing statement” saying he’ll think about following the Suprement Court ruling.

Should.

Won’t.

How can the ruling be a rebuke against Roberts if Roberts ruled against the government when he sat on the appeals court? Either the CNN account is wrong or there’s some flawed reasoning here.

As far as the explosive consequences go, I won’t be losing any sleep because CIA contractors can no longer get their jollies off by waterboarding terrorist suspects or wiring up their genitals to car batteries.

Chris: Roberts ruled against Hamdan originally and recused himself. SCOTUS overturned the DC Circuit ruling.

I’m not losing any sleep over the ruling, either, and have argued for some time that Gitmo was doing us more harm than good. I think SCOTUS is wrong here, though, on the merits. Rather clearly, Congress gave the president wide authority here and, when dealing with enemy combatants, presidents/the executive/the military have always had virtual carte blanche.

The idea that enemies captured fighting American soldiers on the battlefield have due process rights is frankly idiotic.

It’s called “the laws of war,” JJ. Do American prisoners captured by their enemies have any rights, or should we just say “oh well” if they’re shot on the spot? Of *course* prisoners have rights.

I think if you’ll read Stevens’s or Kennedy’s opinions, you may also revise your thoughts on “Congress gave the president wide authority here.”

Scalia’s dissent doesn’t seem to make sense… Even if Congress passed the DTA, it still conflicts, or could be seen to conflict, with CA3 of the Geneva Conventions. The DTA is federal law; so is a ratified treaty. Ergo, the SC had to make some ruling for deconfliction. Just because Congress passed DTA doesn’t end the debate.

Also, the later point JJ highlights,

appeears to be flatly wrong – as noted earlier, this decision does NOT limit the President’s power to conduct military operations, it only throws out the specific mechanism (military tribunals) being used to handle captured bad guys.

Again, five supreme court judges have made it very clear that they are “The Bastards of America”.

These “Bastards” have time and again forced their liberal agenda down the throats of every American without fear of any acknowledgement of accountability to the American people.

The Congress had better act to “Put these judges in their place” and pursue “Articles of Impeachment” against them. They have forced “European” standards and Law on us and totally disregarded the will of the American people.

They should have every bit of their “Security” assigned to protect them removed and made to face the “Wrath of the American people”.

Their “Liberal Agenda” is and will be the downfall of America as we know it.

Say GOODBYE to whatever freedoms you have with these “Bastards” sitting on the high Court

These activist judges are overstepping their bounds. They don’t understand that we are at war. First they allow the American Flag to be burned, now this.

Luckily, Bush said that he is not going to follow the opinion if it jeaprodizes the security of the American People. Thankfully we have a leader with enough resolution to make sure that the rule of law doesn’t get in the way of securing freedom.

Stevensâ?? claim that this might not have meant to apply to Hamden, who was already in custody because â??the Act is silentâ?? on that fact, is plainly absurd.

But isn’t the decisive language in this portion as follows?

The Government acknowledges that only paragraphs (2)and (3) of subsection (e) are expressly made applicable to pending cases, see §1005(h)(2), 119 Stat. 2743â??2744, but argues that the omission of paragraph (1) from the scopeof that express statement is of no moment. This is so, we are told, because Congressâ?? failure to expressly reserve federal courtsâ?? jurisdiction over pending cases erects a presumption against jurisdiction, and that presumption isrebutted by neither the text nor the legislative history of the DTA.

In plain language, Congress could applied the DTA to petitions under para. (e)(1), but didn’t. That’s the ball game, given their express language about pending cases under (2) and (3).

Well, yes. I think Breyer says as much in his concurrence. Glenn Greenwald notes that Congress can overturn most, if not all of the decision, by merely passing a statute.

Ugh:

Congress doesn’t have the necessary anatomy to do anything that does not put a buck into their pockets.

Our glorious Representatives and Senators are nothing more that a lost cause that lines their pockets at the expense of every American while singing their own praises and making speeches telling everyone how they are the “Great Americans”

Congressman and Senators are also the “Bastards of America”

Another interesting aspect of this decision is that it finally answers the underlying question of Ex parte McCardle (1869): absent a 2/3 majority in the Senate willing to remove justices for political reasons (which arguably was present in McCardle, given the political context in which it was handed down), the Court will not recognize jurisdiction-stripping efforts by Congress that attempt to manipulate its docket.

James: “While it has long seemed obvious that the president did not have the authority to term United States citizens â??enemy combatantsâ?? and thereby deprive them of their constitutional rights,…”

Not to the administration, or to Congress.

…”the court has a long history of deferring to wartime presidents in their role as commander-in-chief.”

Remember that Cheney said that this ‘war’ will not end in our lifetimes. A permanent state of war, in terms of presidents-as-commander-in-chief, is a recipe for dictatorship.

” The idea that enemies captured fighting American soldiers on the battlefield have due process rights is frankly idiotic; one suspects the ruling is much more narrow than described by CNN.”

The idea that these people were all, or even in the majority, captured ‘fighting American soldiers on the battlefield’ is known to be false; the US paid Pakistani bounty hunters to produce ‘Taliban’ and ‘Al Qaida’.