The Beginning Of The End Of The Euro?

With the political situation in Greece becoming more unstable by the day and the Franco-German alliance on monetary issues likely at an end, it’s beginning to be hard to see how the Euro survives:

Is there any hope for the euro dream?

One potential way forward would be to create a European- level fiscal union that assumes all national debt, much like what Alexander Hamilton did as first U.S. secretary of the Treasury. That isn’t going to happen in modern Europe. Why would German taxpayers and savers agree to pay for the good times previously enjoyed in Greece, Italy or Spain? Who could even ask them to do so?

As a result, all eyes are turning to the European Central Bank, because some in the euro policy elite still hope loose monetary policy and higher inflation rates will provide an escape hatch. But addressing fiscal issues through monetary means generally doesn’t work, and it does nothing to improve the competitiveness of the struggling euro-area periphery.

It appears that the euro-area politicians and the ECB agreed to a pact last year whereby banks bought government debt, and the central bank provided the financing. In return, the ECB got national governments to sign on to fiscal austerity. So far, the results are disturbing.

Employment levels and leading indicators in Spain and Italy imply the economic decline has accelerated. Greece continues to fall. Ireland is held up as a success story, but its debt levels are enormous, a great deal of fiscal adjustment remains to be done, and the domestic economy declined over the past six months.

Voters are already tired of what they perceive as austerity — see Greece, Spain and now France — and the policy debate has begun to shift. The changed tone of the discussion is gradual but it would be a mistake to overlook this development: Austerity programs have been huge social and political failures, removing one more hope for saving the euro area.

(…)

Here’s what happens next: The euro becomes cheaper, prodded by the ECB taking extreme credit risk and the popular revolt against austerity.

A cheap currency won’t solve Europe’s deeper problems. Depreciation amounts to a nontransparent way for the Germans to bear more of the costs of the failed euro experiment as their purchasing power falls, but investors will still prefer Germany to Greece. It also increases the risk that European and international investors may simply lose confidence in the euro, leading to mayhem in the area’s leveraged financial markets.

For European politicians, the most important task now is to cover their tracks and blame others. Inflation is confusing. It also is an unfair tax on savers and a transfer of wealth to borrowers (assuming that interest rates can be held down or otherwise controlled, probably through nonmarket means). The ECB will now be under great pressure to take actions that create inflation. This may bring the end of the euro.

Paul Krugman suggests that the collapse could come so fast that it would be beyond the power of policy makers or Central Bankers to do anything to stop it:

1. Greek euro exit, very possibly next month.

2. Huge withdrawals from Spanish and Italian banks, as depositors try to move their money to Germany.

3a. Maybe, just possibly, de facto controls, with banks forbidden to transfer deposits out of country and limits on cash withdrawals.

3b. Alternatively, or maybe in tandem, huge draws on ECB credit to keep the banks from collapsing.

4a. Germany has a choice. Accept huge indirect public claims on Italy and Spain, plus a drastic revision of strategy — basically, to give Spain in particular any hope you need both guarantees on its debt to hold borrowing costs down and a higher eurozone inflation target to make relative price adjustment possible; or:

4b. End of the euro.

Each of these events is entirely plausible, of course.

The exit question is this —- if the Euro collapses, what does that mean for the political future of Europe itself? I’ll leave it to people far better versed in these things than I to answer that question.

This should have happened at least 18 months ago in order to avoid needless and counterproductive austerity pain. A Euro breakup or just a Euro to Germny and Benelux will have a nast 2 or 3 year adjustment process but that was in the cards no matter when it happens.

1). In a fiscal union German “savers” (looters in reality) wouldn’t be on the hook for anything. The ECB would just issue the needed reserves to end the debt problem.

2). The ECB has no credit risks and cannot become insolvent because it issues the currency. If needed it will just alter account balances.

3). The euro is too flawed to stand the test of time. With no chance of fiscal union to address currency imbalances a breakup is inevitable. There were people warning of this specific outcome many years ago, but they continue to be marginalized and labelled as cranks and loons. I guess being correct really doesn’t have any value.

@Ben Wolf:

Huh?

Probably very little. The two tracks (EU membership and Eurozone membership) are not really dependent on each other. After all only 17 of the 27 EU states are also members of the Eurozone.

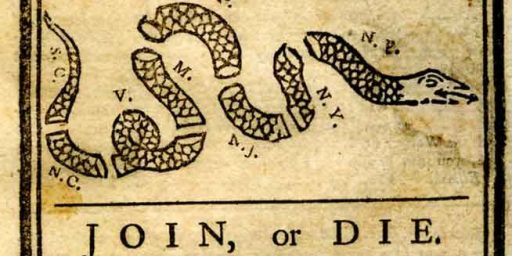

The one thing that is probably very difficult of US citizens to understand is that the Euro was essentially a replay of the European Economic Community. The gamble was that just like economic harmonization eventually led to a political union, a common currency would automatically lead to a federalist structure down the road. The Euro was never a primarily economic project (which also explains the primacy of policy considerations over economic base data in the membership process).

Unfortunately (?) the political environment changed rapidly in the meantime and such a harmonization never took place.

@Stormy Dragon: Germany’s economy is kept afloat by draining the financial wealth of its poorer neighbors via covert subsidization of trade deficits. Without Greek, Irish and Spanish spenders there would be no German savers because Germany would be in the same economic boat.

@Ebenezer Arvigenius: Well put. Economic considerations were certainly of secondary importance in construction of the currency union.

Beginning? There Euro crisis is about 4 years old now (timeline), which as some pundits note, makes it less a crisis than a condition.

@john personna:

Yes, I agree that the crisis has been going on for some time. It does seem, though, that we are at somewhat of a turning point, and that the odds that the Euro survives (which were slim to being with) are infinitesimal at this point.

@Ebenezer Arvigenius:

Well, yes and no. The creation of a common currency was *supposed* to have been an event that united Europe. Instead, it seems to be dividing it even further.

Perhaps what this means is that the idea of a “United Europe” was foolish to begin with, and that a Confederation of states with common interests is the most viable path.

@Doug Mataconis:

I think there were much more desperate calls during the second wave of Greek riots. Things settled down after Merkel and Sarkozy did their deal, in what, this past January?

Here is how one news story begins today:

Basically that’s January all over again. It is (see Nassim Taleb, Black Swan, Fooled by Randomness) “if you can’t predict, try try again.” In this case it is particularly obvious, because it is the same prediction again. If it didn’t work as a prediction in January, try it again now.

It may be that the prediction is this-time-right, but that’s something we can never know. We can never even know the odds. It may happen, or some other short or long term solution may appear.

Wait! Did you lay odds? “infinitesimal?”

So, you are like confident enough to lay me 1000:1?

(lolz, it is important to remember what confidence-words really mean. If the world thought “infinitesimal” was right, they’d be playing that …

Isn’t that the wrong way to trade it? If you face currency risk, you get INTO stocks and commodities. Especially boring ones.

Germany economy is kept afloat by the fact that they have one of the greatest industrial systems of the whole world.

@André Kenji de Sousa: The German government has cheated for years to boost its exports, by subsidizing its industries and violating the Stability and Growth Pact seven out of ten years. Take away its trade surplus and its economy falls. It’s become too much of a one-trick pony.

The same can be said about the US and the domestic market (or the UK & US and the banking sector). This whole “compare to theoretical ideals” stunt is getting somewhat ridiculous.

@Doug Mataconis:

The EU lacks the massive wealth redistribution system that the US has, there’s no equivalent to the federal tax, its size, and how it is redistributed.

Instead the member states of the EU pay a yearly tax based on for example GNI and VAT.

California (35 million people), in 2005, paid $290 billion in federal tax and got back $242 billion.

Germany (81 million), in 2012, paid $30 billion to the EU and got back $15 billion.

Greece (11 million), in 2012, paid $3 billion to the EU and got back $7 billion.

Alabama (4.5 million), in 2005, paid $25 billion in federal tax and got back $42 billion.

So, a confederation of states, with a massive wealth distribution then?

@Ebenezer Arvigenius: The difference is that domestic demand can be stimulated, while Germany’s construction of an export machine has impaired the capacity of its domestic economy to provide growth. Germany has become dependent on financial flows from outside its borders to avoid large deficits; once those flows fall Germany will be in the same position as Greece and Spain, borrowing money it can’t pay back. This is not a problem for the U.S. or U.K. which control their own currencies and do not require financing from abroad.