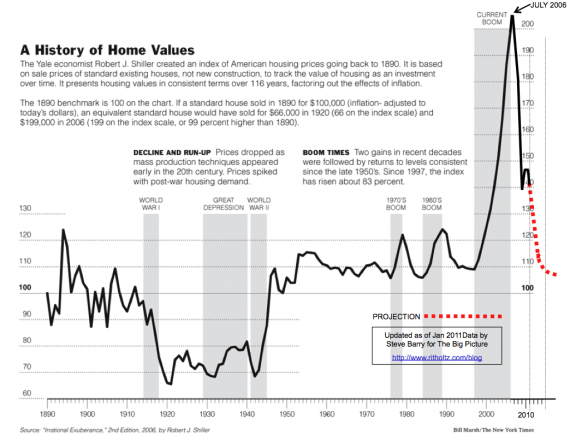

The Housing Bubble Collapse Isn’t Necessarily Finished

One of the co-founders of Case-Schiller home price index says that we may have a long way to go before the housing market hits bottom:

Robert Shiller, the economist who co- founded the S&P/Case-Shiller index of U.S. home prices, said a further decline in property values of 10 percent to 25 percent in the next five years “wouldn’t surprise me at all.”

“There’s no precedent for this statistically, so no way to predict,” Shiller said today at a conference hosted by Standard & Poor’s in New York.

(…)

A model for the U.S. may be Japan, where home prices fell for 15 years after that country’s real estate bubble burst in the early 1990s, Shiller said.

“They lost close to two-thirds of their value,” Shiller said. “Then they went up for one year in 2006 and then they started going down again.”

Forecasting home prices is impossible because there’s no historical precedent for the real estate bubble of the 2000s and the subsequent price drop, Shiller said.

“In real terms, there has never been a bust of this proportion,” he said. “Even in the Great Depression, home prices fell nominally approximately almost as much as they did recently. But that was with all prices falling. So real estate prices didn’t go down hardly at all during the Depression.”

In other words, we don’t know what’s going to happen next, and the housing market is likely to get worse before it gets better. Given the exit to which housing influences so many other parts of the economy, that doesn’t bode well at all. It’s worth noting, for example, that Japan’s “Lost Decade” impacted much more than real estate.

Is that where we’re headed? If we are, then it’s worth noting that part of what made the Long Decade worse was the numerous attempts by the Japanese government and Central Bank to re-inflate the bubble, which seems to be what many in Washington want to try to do. Let’s not make the same mistake twice hoping we’ll get a different result.

I’ve been saying this for a long time. There’s no particular reason to believe that the post-bubble equilibrium prices will be at their post-war norm. Why not back to the pre-war norm? There are demographic and income reasons to believe that might be the case.

Bullshit. I can predict _exactly_ what’s going to happen in the next 2-5 years right now: with housing prices sinking like the Lusitania and rates projected to stay flat, speculators are currently snapping up choice properties, on the assumption that they’ll be able to flip them as soon as the economy recovers & people have money again.

Problem is, that doesn’t look to be happening any time soon. So those properties are going to continue to depreciate, and the speculators are going to panic & get burnt, driving demand (and prices) down even further. Ultimately, the average house in the red now won’t recover it’s pre-crash value for about 10 years.

That’s the future.

Overabundance of supply + lack of demand = lower prices. It’s really that simple.

It’s absolutely correct that the worst thing our policy makers can do here is to throw more federal dollars into the housing abyss artifically to prop up the market. That tax credit from ’09, for example, was the height of fecklessness. When the feds vomit up public dollars to prop up a market all that does is create imbalances that lengthen and ultimately worsen the situtation.

FASB needs to re-instate mark-to-market rules, which in turn will result in many banks going under in short order, including a few “too big to fail” sorts, and bondholders losing their shorts, which in turn will help clear up this mess once and for all. It’s sometimes necessary to destroy in order to build. Then we need to reorganize and to restructure the bad mortgage debt problem with Wall St. investment banks. Similar to the ways in which the FDIC reorganizes and restructures regular banks. This would require legislation and an investment of public dollars, but the payoff would be the necessary deleveraging of the housing market.

The alternative is a slow, grisly death for the American consumer and the economy at large.

Falling house prices are not necessarily a bad thing for sellers. Figure it this way, many (most?) people who sell their houses do so in order to trade up to nicer houses. While they may be getting less money for their present houses, they’ll be paying less for the trade-up houses.

A 3 bedroom, 1 1/2 bath, energy effective home in my neighborhood that sold $75,000 15 years ago. It went into foreclosure and sold for $36,500. The house was not trashed and the neighborhood has not changed. There are several other similar homes like it for sate. We have the lowest unemployment rate in the state 7.8%

I agree that the decline isn’t over, and that the outcome is uncertain.

That’s why I really don’t like that graphic at the top. The red-dotted line implies a most-likely outcome to the general reader. There can be no such thing.

As I understand all the science of market prediction and etc., there is only one tenuous extrapolation possible. That is, markets have momentum. If they are moving in a direction, they have a slightly higher chance of continuing, over reversing.

You can certainly see that in the (black part of the) chart above. Continuations are common, reversals are rare, and unpredictable.