The Real News From The McChrystal Interview: The Troops Aren’t Happy

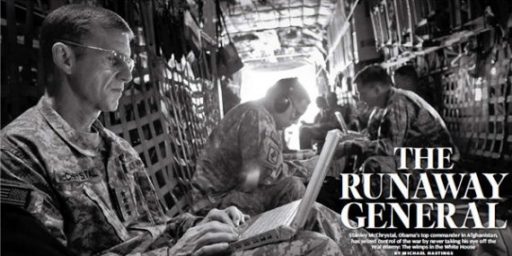

Stanley McChrystal's fate is the story of the day, but there's a broader message in the Rolling Stone story, and it has broad implications for the future of the Afghan War.

While everyone is concentrating, rightfully, on the scandalous and possibly insubordinate comments that are peppered throughout the Rolling Stone story about General McChrystal, there’s another story there too; the troops on the ground are not happy about the counter-insurgency strategy that McChrystal created:

Despite the tragedies and miscues, McChrystal has issued some of the strictest directives to avoid civilian casualties that the U.S. military has ever encountered in a war zone. It’s “insurgent math,” as he calls it – for every innocent person you kill, you create 10 new enemies. He has ordered convoys to curtail their reckless driving, put restrictions on the use of air power and severely limited night raids. He regularly apologizes to Hamid Karzai when civilians are killed, and berates commanders responsible for civilian deaths. “For a while,” says one U.S. official, “the most dangerous place to be in Afghanistan was in front of McChrystal after a ‘civ cas’ incident.” The ISAF command has even discussed ways to make not killing into something you can win an award for: There’s talk of creating a new medal for “courageous restraint,” a buzzword that’s unlikely to gain much traction in the gung-ho culture of the U.S. military.

But however strategic they may be, McChrystal’s new marching orders have caused an intense backlash among his own troops. Being told to hold their fire, soldiers complain, puts them in greater danger. “Bottom line?” says a former Special Forces operator who has spent years in Iraq and Afghanistan. “I would love to kick McChrystal in the nuts. His rules of engagement put soldiers’ lives in even greater danger. Every real soldier will tell you the same thing.”

In March, McChrystal traveled to Combat Outpost JFM – a small encampment on the outskirts of Kandahar – to confront such accusations from the troops directly. It was a typically bold move by the general. Only two days earlier, he had received an e-mail from Israel Arroyo, a 25-year-old staff sergeant who asked McChrystal to go on a mission with his unit. “I am writing because it was said you don’t care about the troops and have made it harder to defend ourselves,” Arroyo wrote.

Within hours, McChrystal responded personally: “I’m saddened by the accusation that I don’t care about soldiers, as it is something I suspect any soldier takes both personally and professionally – at least I do. But I know perceptions depend upon your perspective at the time, and I respect that every soldier’s view is his own.” Then he showed up at Arroyo’s outpost and went on a foot patrol with the troops – not some bullshit photo-op stroll through a market, but a real live operation in a dangerous war zone.

A few days after that foot patrol, one of the soldiers in Arroyo’s outpost was killed while out on patrol and McChrystal returned for a meeting with the troops that turned into a very tense encounter with soldiers who are not happy with the rules of engagement:

Chrystal and his team show up the next day. Underneath a tent, the general has a 45-minute discussion with some two dozen soldiers. The atmosphere is tense. “I ask you what’s going on in your world, and I think it’s important for you all to understand the big picture as well,” McChrystal begins. “How’s the company doing? You guys feeling sorry for yourselves? Anybody? Anybody feel like you’re losing?” McChrystal says.

“Sir, some of the guys here, sir, think we’re losing, sir,” says Hicks.

McChrystal nods. “Strength is leading when you just don’t want to lead,” he tells the men. “You’re leading by example. That’s what we do. Particularly when it’s really, really hard, and it hurts inside.” Then he spends 20 minutes talking about counterinsurgency, diagramming his concepts and principles on a whiteboard. He makes COIN seem like common sense, but he’s careful not to bullshit the men. “We are knee-deep in the decisive year,” he tells them. The Taliban, he insists, no longer has the initiative – “but I don’t think we do, either.” It’s similar to the talk he gave in Paris, but it’s not winning any hearts and minds among the soldiers. “This is the philosophical part that works with think tanks,” McChrystal tries to joke. “But it doesn’t get the same reception from infantry companies.”

During the question-and-answer period, the frustration boils over. The soldiers complain about not being allowed to use lethal force, about watching insurgents they detain be freed for lack of evidence. They want to be able to fight – like they did in Iraq, like they had in Afghanistan before McChrystal. “We aren’t putting fear into the Taliban,” one soldier says.

“Winning hearts and minds in COIN is a coldblooded thing,” McChrystal says, citing an oft-repeated maxim that you can’t kill your way out of Afghanistan. “The Russians killed 1 million Afghans, and that didn’t work.”

(…)

As the discussion ends, McChrystal seems to sense that he hasn’t succeeded at easing the men’s anger. He makes one last-ditch effort to reach them, acknowledging the death of Cpl. Ingram. “There’s no way I can make that easier,” he tells them. “No way I can pretend it won’t hurt. No way I can tell you not to feel that. . . . I will tell you, you’re doing a great job. Don’t let the frustration get to you.” The session ends with no clapping, and no real resolution. McChrystal may have sold President Obama on counterinsurgency, but many of his own men aren’t buying it.

One has to imagine that these attitudes are not limited to just this unit, but represent a fairly good picture of how many of the combat troops in Afghanistan feel at this point.

While we will be focused for most of today on the fate of one man, perhaps it’s time we started asking ourselves how our current strategy in Afghanistan can possibly succeed if the troops on the ground don’t think it will work.

No one who understand COIN, wants to do it. Rough paraphrase of Exum. One of the main reasons McChrystal was chosen to conduct a COIN operation was his reputation as real warrior. This was not some pansy-ass desk jockey with some think tank theory. He was the real deal. It was hoped he could sell the troops on COIN with his reputation providing it credibility.

We were lucky in Iraq. The SOI came over to our side even before the surge started. The ethnic cleansing was largely finished before we began COIN ops. Iraq is more urban and doesnt have a mountainous border with a safe haven conveniently at hand. Any undertaking in Afghanistan was gonna be hard. A COIN campaign especially so.

Steve

This is a serious question: Is the US capable executing a war with expediency and resolve, rather than as a holding action and public relations exercise?

Our enemies seem to.

@Drew:

In 2001 the US took Afghanistan (a place that had previously resisted the Soviets, British, and Ghengis Khan) in a couple of months. From a cold start.

A couple of years later the US defeated the Iraqi military and took Baghdad in even less time.

The current campaign in Afghanistan isn’t a war. It’s a counterinsurgency, and nation-building exercise.

Wrong question.

Why do we think the troops on the ground have any better insight into long-term strategy? Long term thinking is counter-productive for ground troops: their interests are in surviving day to day. This is not to disparage the troops — optimizing for the short term keeps them alive for another day — but it’s why they’re required to follow orders.

Upset because insurgents are turned loose due to lack of evidence? Perhaps what our soldiers need is a remedial civics course. Requiring evidence is part of our American ethic, and objecting to *that* just marks one as a bully and wannabe tyrant.

@Mattt is right about this being a nation-building exercise. The normal rules of combat don’t apply. The best way to save the lives of soldiers is to get them out of there and bring them home, and the best way to do that is to build a nation, and _not_ to shoot anyone who looks at you funny.

Of course, we could just give every man, woman, and child in the country an M16 and a case of ammunition, and then wish them a happy bloodbath as we leave. That doesn’t seem as morally satisfying, however.

Best would have been to never go at all. We didn’t accomplish the goal (capture Osama — remember Osama? This is a war about Osama.) we started with, and now we’re having to clean up the mess. Cleaning up a mess is always unpleasant, but you can’t start cleaning it up until you stop making it worse.

I’d like to take my queue from the Special Ops Soldier in the article and kick SJS in the nuts. I’d elaborate on my distaste for his comment, but I’ve had enough of my share of backwards thinking like that and don’t want to drag out a debate.