Van Halen Principle

Ezra Klein has a really smart piece titled "How Van Halen explains Obamacare, salmon regulation and scientific grants."

Ezra Klein has a really smart piece titled “How Van Halen explains Obamacare, salmon regulation and scientific grants.”

Right there on Page 40, in the “Munchies” section, nestled between “pretzels” and “twelve (12) Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups,” is a parenthetical alert so adamant you can’t miss it: “M&M’s,” the text reads, “(WARNING: ABSOLUTELY NO BROWN ONES).”

This is the famed rider to Van Halen’s 1982 concert contract. In a sentence fragment that would define rock-star excess forevermore, the band demanded a bowl of M&M’s with the brown ones laboriously excluded. It was such a ridiculous, over- the-top demand, such an extreme example of superstar narcissism, that the contract passed almost instantly into rock lore.

It also wasn’t true.

I don’t mean that the M&M language didn’t appear in the contract, which really did call for a bowl of M&M’s — “NO BROWN ONES.” But the color of the candy was entirely beside the point.

“Van Halen was the first to take 850 par lamp lights — huge lights — around the country,” explained singer David Lee Roth. “At the time, it was the biggest production ever.” Many venues weren’t ready for this. Worse, they didn’t read the contract explaining how to manage it. The band’s trucks would roll up to the concert site, and the delays, mistakes and costs would begin piling up.

So Van Halen established the M&M test. “If I came backstage and I saw brown M&M’s on the catering table, it guaranteed the promoter had not read the contract rider, and we had to do a serious line check,” Roth explained.

Call it the Van Halen Principle: Tales of someone doing something unbelievably stupid or selfish or irrational are often just stories you don’t yet understand. It’s a principle that often applies to Washington.

Klein offers several examples of seeming bureaucratic stupidity that have come under prominent derision, all of which make perfect sense when examined thoughtfully. He concludes:

It would be nice if the government’s mistakes were typically a product of stupidity, venality or bureaucracy. Then we would need only to remove the idiots, fire the villains and cut the red tape. More often, the outrageous stories we hear are cases of decent people trying to solve tough problems under difficult constraints that we simply haven’t taken the time to understand. That isn’t to suggest that people in government don’t get it wrong. They do, repeatedly. But if we want to get it right, we need to work harder to understand why they decided to remove the brown M&M’s in the first place.

Two caveats.

First, there are a lot of brown M&M policies that made perfect sense when enacted whose original purpose has long since been obsolete but nonetheless continue through inertia or because some small, powerful group benefits greatly from continuing them.

Second—and conversely— there are a lot of seemingly outrageous incidents that are artifacts of the way bureaucracy works. Almost all of the stories of government bureaucrats paying $16 for muffins are of this type.

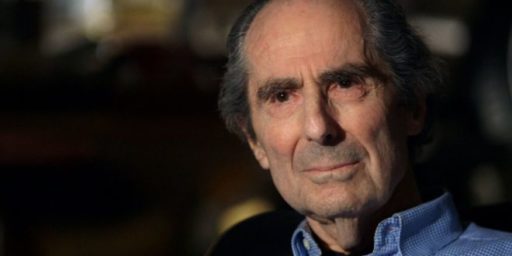

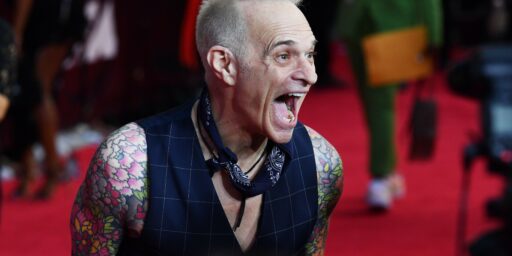

Oh, and watching David Lee Roth explain the brown M&M story while inexplicably dressed as a train conductor is priceless:

Unfortunately, most of government ‘Van Halen Principles’ are more like some other ban adopting the brown MM clause but not knowing the real purpose of the clause. They just use it because that is what Van Halen did.

Or a procedure is adopted as a way to get around a rule that has prohibited some bureaucrat favored action.

“We removed the brown M&Ms because we could.”

That certainly explains why they passed that pile of excrement called ACA

On a similar note there’s G. K. Chesteron’s quote “Don’t ever take a fence down until you know the reason it was put up.”

Greetings:

Don’t train conductors usually wear uniforms as opposed to overalls ???

@edmondo:

You have provided another example of the Van Halen Principle

They passed it because it was the best that could be accomplished in the political realities that it had to be crafted under.

POS it is, but then so is the status quo. As Eisenhower once advised, only partially tongue in cheek: “Whenever I run into a problem I can’t solve, I always make it bigger.”

Actually, this is NOT a very smart piece. It is an interesting observation followed by several non-sequiturs, including an obviously stupid statement that reflects back on Ezra Klein.

First, note that the M&Ms clause is about signalling and lowering information costs — Van Halen wanted a “cheap” way to determine if venue owners were paying attention to their contract. This was brilliant. Go Diamond Dave!

However, the Obamacare amendment has nothing to do with signalling, but is instead a “poison pill” put into the bill to prevent its passage or create political embarassment down the road.

The salmon regulation discussion has very little relation to the signalling aspect of Van Halen’s M&Ms clause. I can’t even figure out why that was in the article other than Klein wanted to talk about it. The bigger story there is that the more you engage in regulation of various activities, the more you will find exceptions that require more regulation. This feeds both the rent-seeking desires of a regulated industry AND its associated regulatory agency. Nothing better than providing more jobs by creating more rules to monitor.

The “shrimps on treadmills” and NSF grants is also a complete non-sequitur in relation to the M&M clause. Yes, NSF (and other) grants can look like they are doing weird things (shrimps on treadmills) that have more important purposes (calculating bacterial resistance), but Ezra seems to jump to the conclusion that oversight of these grants is bad. How is that related to M&Ms? If anything, the title of NSF grant should be an M&M clause that triggers more careful attention and indicates whether the agent (researcher) is acting in accordance to the principal’s (taxpayers) desires.

The following sentence in the article is just astounding to me: “Coburn’s attack is particularly dangerous because it encourages government researchers to conduct science that sounds good rather than science that does good.” Actually, Coburn’s committee oversight seems entirely appropriate and there are plenty of other incentives other than an oversight committee that make researchers do research that “sounds good,” including getting the fame following being mentioned in an article by Ezra Klein.