A Quote to Ponder

“I think that, first of all, the United States should remember that we have spent the last 15 years trying to use military power, including military assistance, to try and organize the politics of this region. And we have failed miserably.

We have got a failed state in Iraq. We have a failed state in Libya, and we spent $25 billion training the Iraqi army, which then subsequently turned and ran when confronted by ISIS. So I think to believe that we can go in again with airpower primarily and some special forces and eliminate this problem is fanciful.”—Stephen Walt on calls for military action against ISIS.

Speaking as one who supported the 2003 invasion of Iraq (and later regretted that support), I would state that it would be nice if we would we pause and try and learn the lessons of the last decade plus instead of letting runaway rhetoric about ISIS being a direct threat to the US guide policy decisions.

Don’t sell us short here, we started the failed state experiment in Somalia.

American elites appear eternally convinced of their power to manage the forces of history, no matter how unsuccessful past efforts. It’s an isolated and inbred viewpoint that renders them insensate to reality.

Such a waste of lives and money.

I think the problem here is that its possible to point to examples of failures of interventionism AND non-interventionism.

After all, we didn’t intervene in Afghanistan after it started to fall apart after the Soviets left in 1990-and the result was 911.

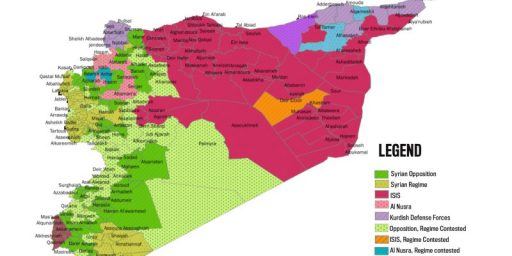

More recently, we didn’t intervene in Syria in the aftermath of the Arab Spring-and the result is the rise of ISIS.

The fact is that non-interventionism also has its failures. ( Indeed, it’s arguable that the biggest non-interventionist failure of all was failing to act against the rise of the Nazis in 1930s).

Maybe just applying a consistent interventionist or non-interventionist approach doesn’t work and you have to evaluate every emerging FP crisis on its merits.

@stonetools:

This is a reasonable position.

However, the issue would still require starting with a few key questions:

1. How often does intervention actually work?

2. To what degree do we have evidence that intervention into a situation such as this is likely to be successful?

@stonetools:

I would note on this observation, however, is that ISIS is anti-Assad. Had we intervened in Syria against Assad it is very possible that ISIS would be stronger and even more active (and perhaps even ruling Syria).

@stonetools:

Although, we did intervene (covertly) in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation to fund the Muhajadeen, and many of them became the Taliban.

Anything we do is considered by most over there to be meddling. And for a significant fraction of those, it is meddling being done by a sworn enemy. I just don’t know how we’re going to win hearts and minds by constantly dropping bombs on them.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Those are good questions. Often, though, non interventionists simply seem to assume that :

1. All interventions must fail.

2. There are never situations that interventions are likely to be successful.

That’s not a helpful approach either.

Also too, non-interventionists also seem to assign no costs to non-interventions. Unfortunately, non-interventions can be costly too, especially if it leads to interventions later. It’s a lot easier to put out camp fires than raging forest fires.

@Steven L. Taylor: @Steven L. Taylor:

The theory of early intervention in Syria was to build up a moderate armed opposition to Assad in order to forestal (and fight against) a Sunni jihadist armed opposition.

The theory was that in the absence of a moderate armed poosition, the rise of a Sunni jihadist armed opposition to fill the vacuum was inevitable.

The Obama Administration’s theory was to hope that the initial unarmed moderate uprising would result in a 1989 type “velvet rebellion.” Unfortunately, 2010 Middle East wasn’t like 1989 eastern Europe.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yeah. Maybe we should have continued intervention after 1989 with rebuilding Afghan civil society rather than creating armed militias and leaving THEM to decide what course Afghan society would take. Shows that intervention has to be carefully thought out, and may have to be deeper and longer lasting than we might like.

The point here is that the intervention\non intervention question isn’t quite the simple one people on both sides think.

1) Had we intervened in Syria the most likely outcome was not democracy. The most likely outcome would be ISIS sitting in Damascus today atop a heap of bodies. They’re better fighters than the alleged “moderates.” To avoid that outcome we’d have had to simultaneously attack Assad and ISIS and hope our freedom fighters somehow had the capacity to defeat both at once, and then hope that this faction could maintain control in the aftermath. I’ve misplaced my rose-colored glasses so that outcome doesn’t look terribly likely.

2) Can someone please explain how ISIS threatens the US? What we face now is stateless terrorists, so we have a very hard time hitting them. ISIS would have a big fat target painted on its back. They need to pump oil and keep the infrastructure going – not so easy when the Americans are bombing the hell out of you in retaliation for terror attacks.

3) As a rule I’m all for bombing barbarian scum like these. I like it when evil men die. But we need to stop kidding ourselves that the result is a middle-eastern Vermont. The Arab middle-east is not IMO ready for democracy. The institutions don’t exist, the level of education doesn’t exist, the culture that would underpin democracy ain’t there, and the religion is about where Christianity was 500 years ago when Christians were massacring other Christians – men, women and children – for having a slightly different interpretation of the gospels.

CNN news article this morning shows teens being trained by ISIS. It is enough to make your hair stand on end. It makes the Hitler youth look like a Boy Scout troop. They starting them out young over there. Next thing you know they will send them over here. ISIS has passports . Based on the way people have been pouring into this country illegally by the bus load, they won’t have any trouble getting in.

@stonetools:

The problem is, that is less a theory than it is a hoped-for fantasy as it assumes that there is “moderate armed opposition” to identify and cultivate and that, further, such cultivation would not also help non-moderate armed opposition groups.

@stonetools:

1) What would have been the rationale to more deeply intervene at that point?

2) We did provide to Afghanistan after the Soviets left.

3) You can guess who we gave the aid to (which would have been the same people we would have supported with an even deeper intervention: our allies who fought the Soviets).

4) A deeper intervention in 1989 would have provoked the Soviets, who still exists are at the time.

Your theory of intervention seems predicated on the assumption that there is a right way to do it in each case, which is likely not true. The best intended, best funded, best planned intervention can still be a disaster.

Also: much of this is predicated on what “intervention” means. It is not as if, for example, we are currently hands-off in Iraq.

@Tyrell:

First: which is it: are we supposed to be afraid of ISIS rolling in over the Mexican border or are we supposed to be afraid of their passport-wielding legal entry?

Second: what is this based on save from pure paranoia?

@Steven L. Taylor:

I’m monitoring FOX News now to find out which…I’ll let you know.

@stonetools:

I have one simple rule: First, do no harm.

@stonetools: Top of the head examples of successful interventions:

Korea

Grenada (which couldn’t fail as the threat was largely imaginary)

Panama (the goal was so modest, arrest one guy, it would be hard to fail)

Maybe Desert Storm

??

Without much effort I could come up with a much longer TOTH list of failed interventions.

The 2003 war in Iraq accomplished ceding power in the region to Iran, arguably the country in that region that we have the most animus toward. By taking out Hussein we completely destabilized the region. I doubt that the Bush Administration considered that that would be an outcome (a result) with high probability. I’m sure that they calculated that by taking Hussein out they and the Iraqi people would install a less dictatorial leader and everyone would move forward from that.

The same could be said for Libya, or Egypt. Our involvement aside, there are political movements and undercurrents all through that region – from Libya to Central Asia and Iran that we cannot control, that we cannot influence for our geopolitical objectives.

We cannot bury our head in the sand, however to adopt interventionist policies is to mire ourselves in quicksand. We need to be extremely cautious as the battles and interventions we undertake.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Remember, moderates led the initial uprising, so its not a fantasy to say there was a moderate opposition to cultivate.

We just didn’t try because no one wanted to get any further involved and we hoped that things would somehow work out for the best. Well, in the Middle East, that doesn’t happen.

Now would have arming the moderates worked? It certainly isn’t a sure shot, but it was inevitable that jihadists would have arose to fill the vacuum in the absence of us doing nothing, and lo and behold, that’s what happened.

Non interventionists kept hoping that the two sides would kill off each other or the conflict would burn it self out or be limited to Syria. Instead the conflict escalated because hey, that’s what happens in the Middle East , and now we’re fighting Syrian jihadists in Iraq.

Looking back on it, its hard to believe that arming the moderates could have worked out worse than doing nothing. I’ll say that both options were supportable so I don’t fault the administration or the non-interventionists for pursuing the non-interventionist option. There ain’t no such thing as a sure shot option in the Middle East.

@al-Ameda: This is why I said above “maybe” Desert Storm was successful. In my mind it wasn’t. Maybe if we’d liberated Kuwait and kept it. More seriously, I’ve seen speculation about whether it would have been better to let Iraq keep Kuwait rather than return it to people who help the Saudis fund all the craziness in the Middle East. And cynically I wonder if we wouldn’t have let Iraq have it had BushCo not been a wholly owned subsidiary of the Saudi royal family.

Yes, ultimately our screwing around in Iraq has strengthened our enemy, Iran. And Iran needn’t have been an enemy except for blowback from our intervention there in the 50s. Our overthrow of their government is the classic example of an ostensibly successful intervention turning horribly wrong in the long term.

@gVOR08:

World War 2, the Berlin airlift, and the Marshall Plan are big examples of successful interventions. More lately, there’s Bosnia and Kosovo (although those results are mixed).

Non-interventions that failed are failures to act to prevent the rise of militaristic regimes in Germany and Japan in the 1930s and more lately, Rwanda ( Gotta count non-interventions that led to disasters).

@stonetools:

I would submit that our success rate with intervention is likewise poor, and it costs a lot more than non-intervention.

@stonetools: How could we have intervened to stop the rise of Germany and Japan pre-WWII? This kind of assertion makes me think you have an unrealistic view of what can and cannot be accomplished.

Also, there is some serious apple/oranges going one here: Berlin Airlift and militarily intervening in Iraq against ISIS are rather radically dfifferent.

Likewise, I would not put the Marshall Plan in the same category as what we are discussing here. (as it was peaceful economic investment with willing partners).

@stonetools:

No, but it is wishful thinking in the extreme to assume that the right intervention in a situation like Syria’s would lead to the establishment of the moderate in power. If anything it has to be recognized that in a situation such as Syria any help to the moderates would also be help to the radicals.

Further. those who appear moderate at the beginning often end up not being moderate once in power.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Again, non-intervention is chaper if you don’t have to intervene with greater force later as we are doing right now.

@Steven L. Taylor:

These were interventions-just not military ones. Intervention is not necessarily military.

I don’t really think that there is an iron law of interventions that dictates a particular result like that.In the case of Syria you wouldn’t be looking to turn Syria into Switzerland-you would just be looking to cultivate a moderate opposition. . Had we armed the moderates there would have been a chance that the moderates would win, or at least influence the outcome-not a good chance, but a chance.Not arming the moderates made it a certainty that they would lose and that jihadist armies would rise to become the only opposition.

@stonetools: The Marshall plan was not an intervention. None of the affected states were under attack. You are really reaching with that example and undermining your argument in the process. One might as well argue that NAFTA was a successful intervention.

@stonetools:

The rather profound problem with that logic is that part of the reason that we have to contemplate a vigorous intervention at the moment is because a previous vigorous intervention took out the Iraqi state.

@stonetools:

This is, of course, true. However, two important points:

1, In your quest to find examples of positive intervention you have rather broadly expanded the definition. Again: the Marshall Plan was a cooperative, mutually consensual arrangement. I am not sure that fits “intervention” in the mold of directly inserting national power into a context in which key actors would prefer you stay out (and where the goal is to alter the behavior of those actors).

2. Beyond definitional debates: we are talking here rather specifically about military intervention , so it seems rather pointless to try and use non-military examples to make a case one way or another.

No, there is not iron law of intervention. However, you were the one suggesting counterfactuals in which the moderates in Syria could have won.

This is only true if the moderates are large enough to actually beat BOTH the regime AND the radicals. Are you really going to suggest this is the case? Just being backed by the US does not guarantee such an outcome. And even when the side we back wins, there is no guarantee they will behave as we wish (see, e.g., Viet Nam, Iraq, and Afghanistan).

@stonetools:

Or some of those moderates you were looking at weren’t. Which is why Obama didn’t send them aid. Sure, in an ideal world all the good guys would wear white hats and the bad guys would wear black hats so we could tell them apart, but the real world doesn’t work that way.

But there was an even better chance of those arms ending up in the wrong hands. Just like they did when ISIS invaded Iraq.

In battles, the motivated tend to win. Or to put it another way, nobody (sane) ever died for a Diet Coke. An Islamic Caliphate? Hmmmm……

Yes, not doing something has risks as well, but in my memory every really big mistake we have made that we had to pay for (I mean really pay for) since WWII came about as a consequence of our own stupid actions. There is no way Iran should be an enemy of ours. That is a relationship that should have long ago been repaired just like with Vietnam. But every chance we have had to “don’t just do something, sit there”, oh nooooo, we had to get involved, we had to do something.

@OzarkHillbilly:

Even better: if the CIA hadn’t ousted a democratically elected government in 1953 to place the Shah back on the throne, think how different the development of the ME might have been.

Again: we are paying for that intervention even to this day.

@Mu:

Off topic, but everyone who thinks Somalia was a failure doesn’t know what we went there to do. And did. Seems to be about 98% of the US public fits that discription.

On topic, Walt has created several straw men. AFAIK, nobody is saying air strikes and “a few special forces” would solve everything, and not everything is about nation building. There is also a logical fallacy of past results dictating all future events. If the Iraqi Army had folded there would be a different government in Baghdad now. Four divisions folded and by Chiver’s accounts it appears to have been ISIS succeeding in turning some officers in at least three of those four divisions. A neat trick, only having to turn a few underpaid and disgruntled officers not withstanding.

Stephan “Why the Tunisian Revolution Won’t Spread” Walt has a good point under all that silliness though. We need to think about what we want to accomplish and match that with a realistic assessment of what the US public will support and for how long they will support it. I think his cynicism isn’t worth much, is all.

@stonetools: Alas, in your Wikipedia article, Assad appears to be one of the moderate forces–at least until his change of heart and the arrests. Another problem with finding the moderate element in the ME–it may not be what you think it is.

Having read this comment thread, I am reminded of something a co-worker used to say:

“If you wish in one hand and spit in the other, I can tell you with almost 100% accuracy which hand will fill up first.”

@Steven L. Taylor:

Nice quip, but it doesn’t answer my main point, which is that non-intervention isn’t cheaper if you have to intervene later, with greater force.

Not necessarily. As you know, there are many revolutions in which several disparate groups combine to defeat the ruler, who is stronger than any single group. The Mexican Revolution is one example; another is the 1980s Afghan uprising against the Soviets. Indeed, in the present situation, there are several jihadist militias fighting against Assad, plus the Kurds. Training and equipping a moderate militia to fight alongside those others looks possible. What you want is is to have YOUR boots on the ground alongside the other forces to give you some options other than just wringing your hands.

Now it would be ideal if you don’t intervene and things somehow work out, the way non-interventionists had hoped. But that’s not what happened. What happened is instead is that the US is providing close air support and committing “advisors” on the ground in 2014 in Iraq versus supplying arms and equipment to local forces in Syria in 2011, and is now thinking about carrying out a campaign in Syria-including sending in (more?) special forces.

Now, its not like the USA can NEVER succeed with funding guerilla movements. They certainly can (although results have been mixed). Its not a sure fire solution; but there are no surefire options in the Middle East, INCLUDING non-intervention. THAT’s something to ponder.

@stonetools:

It is not a quip–it is an observation that interventions can have long-term, unintended, and expensive consequences.

You keep arguing in a very abstract, hypothetical way that seems to start with the assumption that there is a right way to intervene that will lead to success (e.g., your argument about supporting moderates in Syria)–i.e., you seem to assume that if done right (pick the right allies. employ the right strategy) that the outcome will be positive. You cannot assume this to be the case

You also seem to think that I think that non-intervention will lead to good outcomes. That is not my argument. Indeed, it is likely that both intervention and non-intervention will lead to undesirable outcomes. The question is: which route costs less (in lives, treasure, etc.)? Looking at these situations as if they are controllable is part of the problem (and it was the problem going into Iraq). We should have learned a lesson about our power capabilities in Iraq–and that is what the Walt quote points to. (Or, at least, that is what I arguing should be pondered).

I never argued that anything is surefire. I am arguing, however, that a) our record of intervention, especially in the region is not that good, and b) the cost of intervention is certain, while the cost of non-intervention is less clear.

Forget the abstract: how heavy of an intervention do you want to have in Iraq right now? And, moreover, why do think it will be worth the cost?

Further, I will note that you are making the same kind of theoretical arguments about intervention in Syria and Iraq now that were made about Iraq in 2003–all predicated on a vague what if?’ scenario if we did nothing. Iraq 2003 did not work out as planned, not by a long shot. As such. a pause to think this through strikes me as worthwhile.

Why are you so hellbent on the notion that intervention can work out?

Side note:

I am unclear how the Mexican Revolution is a relevant example here (sincerely: I don’t see any parallels of note).

The Soviets in Afghanistan was a scenario about expelling an imperial power. That tends to unite the locals against the outsiders. ISIS is different in that it has ethno-religious ties to many of the people in western Iraq. It could be seen not as a invading force, but as one of unifying people with similar religious an ethnic identities (while expelling, killing, or converting those that don’t belong). This is a very different dynamic.

Part of the problem with your approach to this subject is that a) you have a very vague definition of intervention, and b) your historical analogies are largely quite imperfect in terms of a source of relevant lessons in this context

@Steven L. Taylor:

With all due respect, I don’t think I am arguing in an abstract way, etc. Nor am I argiung that my way will inevitably lead to success. Quite the contrary. My point is that ALL options are difficult . I’ve pointed out that it is the non-interventionists who are assuming that non-intervention is the “cheapest” option, to use your characterization.

Surely, two can play at that. Why are you hellbent on showing intervention can NEVER work?

Firstly, there are no perfect historical analogies. I’m pointing out that revolutions often involve several disparate groups fighting against a ruler. Secondly, I believe that we were specifically talking about fostering and arming a Syrian moderate group back in 2011-13. Back then, non-interventionists strenuously argued against that as being unnecessary. They argued that it would draw us into a conflict that we should avoid simply by “sitting this one out.” The pro and anti Assad forces would “destroy themselves” , the conflict endangered no US assets, etc. Today of course, we are involved at a much deeper level than just supplying arms and are about to be involved even deeper still. And we are pursuing the strategy non-interventionists argued against in 2011-3:arming moderates.

One pundit put it this way, in pungent fashion:

He also proposes a strategy (which I’m not sure I endorse, but at least it’s specific):

Now this strategy goes far beyond what Obama has so far proposed he would do: maybe even beyond what he politically can do. And, of course, like EVERY option, it’s not surefire. But at least it has the look of a coherent intervention strategy. One thing we know WON’T work is sitting and waiting for things to get better. That just hasn’t worked at all, and IMO ain’t going to work.

Please free my comment from moderation. I originally forgot to disguise a profanity in a quote. I have now done so. Thanks.

@stonetools:

This isn’t a strategy, it’s ad hoc reactionism. Firstly there are virtually no moderates to arm in Syria, nor are our intelligence services in a position to determine who is and is not trustworthy with our weapons. Secondly, we have thirteen years of data telling us that bombing campaigns deliver mixed results at best; given that most targets are located in cities controlled by the Islamic State, significant civilian casualties would be inevitable and therefore poses the real risk of strengthening popular support. Thirdly, a no-fly zone is a virtual guarantee of eventual U.S. ground intervention against the Islamic States’ most bitter enemy, Bashir al-Assad. It’s in our greater interests to keep him there, not to destroy any effective resistance to Islamic fundamentalism as we did in Iraq and Libya.

Each recommendation is another method of shooting ourselves in the foot.

@Ben Wolf: Sorry for the italics vomit, I seem to have forgotten the closing part.