A Military Stretched Thin

Sydney J. Freedberg Jr. has an excellent piece in the current National Journal entitled, “A Military Stretched Thin.” It’s a candid but fair assessment of President Bush’s efforts at transforming the military, a major plank of his 2000 campaign platform.

“Commander-in-chief.” No other phrase captures so concisely the power of the president. In no other arena is the president’s power so unconstrained as it is in national defense. With the War Powers Act a dead letter and Congress unusually compliant, he can commit the world’s most potent military virtually at will, staking American lives, treasure, and prestige with consequences — intended and otherwise — that ripple down the decades. And yet, at the same time, in no other arena is the power of the president so severely restricted. It takes years to recruit, organize, and train new units of troops. High-tech weapons require one or two decades to develop, and even policy pronouncements must grind laboriously through the bureaucracy before they can emerge as executable plans. The commander-in-chief may wield the sword unchecked — but it takes years of labor and myriads of people to reforge that sword.

This captures the situation in a nutshell. Presidents can do more in their role as commander-in-chief than in virutally any other arena, yet truly changing a military is something that even a two-term president can only begin. Changes started under the Carter Administration in the 1970s, accelerated and aggressively funded under the Reagan Administration in the 1980s, finally saw fruit in the first Bush Administration in the 1990s.

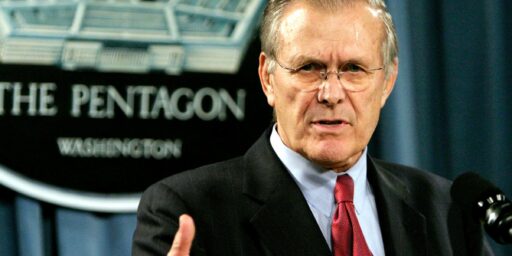

Freedberg reviews the Bush campaign promises and notes that the changes were meeting stiff resistance during the early months but that Bush and Rumsfeld had something approaching carte blanche in the wake of the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Of course, the reality on the ground changes as well.

The pre-9/11 Pentagon was also abuzz with the Rumsfeld team’s consideration of cutting Navy aircraft carriers and two of the Army’s 10 combat divisions. Global war wiped out those plans. But even after the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, Rumsfeld continued to push the Navy and, especially, the Army in a way he never did the Air Force. There was no “skipped generation,” but the administration made real cuts, and real additions.

More subtle, but more radical, than any new construction are proposed changes in how the Navy operates its ships. The traditional round of deployments — six months deployed overseas, 18 months refitting and training, repeat — has already yielded to the demands of supporting the Afghanistan and Iraq invasions. Now the Navy is making such “surges” standard procedure. Under a plan called “Sea Swap,” ships do not sail back after six months but instead have their current crew flown home and replacements flown in. This plan reduces the number of ships required to maintain forward patrols.

In one sense, there’s nothing new here. All of these ideas originated within the Navy itself, back in the 1990s. The first Sea Swap exercise was under way before Bush’s inauguration; seabasing supersizes existing support ships to enable a long-held Marine desire to strike deep inland; and the Littoral Combat Ship was conceived by Vice Adm. Arthur Cebrowski in 1998. But it took the Bush administration to shove Cebrowski’s idea into the budget, and to elevate Cebrowski himself from a lone maverick to director of Rumsfeld’s special office for transformation. Similarly, Adm. Vernon Clark, the chief of naval operations, is pushing all these changes, and was first appointed under Clinton. But it was the Bush administration that backed Clark’s program against Navy traditionalists and gave him an extra two years as chief to implement it — an extension in office unequalled by any chief since the legendary Arleigh Burke, who oversaw the introduction of missiles and nuclear power to the Navy from 1955 to 1961. “What has been the Bush impact on the Navy?” asked one congressional source. “It has been to make Clark probably the most powerful chief of naval operations we’ve had in a long time.”

Indeed, the most important impact of the Bush administration may not be in programs but in people. Although the administration has hardly equaled the mass firings of old officers by Gen. George Marshall at the start of World War II, “what Rumsfeld has sought to do is nothing less than a complete recasting of military culture … by ruthlessly replacing representatives of ‘old think’ with a cadre of senior officers sharing his views,” said Loren Thompson, a well-connected consultant to defense contractors and an analyst at the Lexington Institute. In contrast to Clinton-era officials, Thompson said, “Rumsfeld has not been afraid to criticize and second-guess and punish the most senior of officers.”

Nowhere has this harsh mode of management been more apparent than in the Army. When selecting a new chief of staff last year, Rumsfeld passed over every active-duty general officer to name a retired commando, Gen. Peter Schoomaker. The previous chief, Gen. Eric Shinseki, had pushed what was then considered a radical transformation program under Clinton, but he found himself hammered by Rumsfeld as too conservative. The administration canceled the Army’s high-tech Crusader cannon as too heavy to transport to distant battlefields; conversely, it criticized the Army’s air-deployable Stryker armored vehicle as too light to survive on its arrival in battle. (The Stryker survived the skepticism and is now used in Iraq.) Schoomaker continued the cuts by canceling the Comanche scout helicopter, the Army’s prize aviation program.

But these cuts do not mean that the Army is “skipping ahead” to any radical new weapons. Quite the contrary. The Comanche funds are going to repair and upgrade the current helicopter force, flown hard and shot up in Iraq and Afghanistan. And the centerpiece of Shinseki’s program to re-equip the entire Army with high-tech vehicles, the Future Combat System, is in budgetary trouble and is likely to be reconceived as a test bed for technologies that can be spun off into the current force. Supplemental requests have focused on funding near-term needs, such as up-armored Humvees, missile-jammers for helicopters, and body armor.

Yet this is not a simple retrenchment. Even more so than in the Navy, the transformation in the Army is not about new superweapons but about new ways of using the hardware already on hand. The Army has sped up the fielding of computer communications networks for retrofitting onto existing armored vehicles; it has begun reorganizing its brigades for the high-speed, widely dispersed operations — closely coordinated with air support from the other services — that those networks enable; and it has started overhauling its personnel assignment system to produce stable teams of troops ready to deploy on short notice. (See NJ, 1/31/04, p. 314.)

As someone who wrote a doctoral dissertation on defense tranformation in 1992 (before it was called defense transformation) and studied it very closely ever since, the scope and especially rapidness of the changes took me by surprise. Bureaucratic resistance has been the norm for decades. While it’s clearly still there, Rumsfeld and company have rammed through needed changes.

As one might imagine, however, doing all of this in the face of the biggest war in over a generation has its downsides.

War imposes change. It also stifles change. The same immediate demands that impel troops to adapt or die also devour resources that could be invested in lasting transformation. Although post-9/11 defense spending is comparable, in constant dollars, to the height of spending during the Cold War in the mid-’80s — when much of the current equipment was built — “in the Reagan buildup, virtually all the money was going for modernization. Now a huge chunk is going for consumables,” such as fuel, ammunition, and spare parts, said Steven Kosiak of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. “It’s not going to have the same kind of long-term impact on U.S. defense capabilities.”

The stress of war has hit all the services, but none harder than the Army. The crucial shortfall is not in money or machines, but in manpower. Of the Army’s 500,000 soldiers, almost 140,000 are in Iraq, and they are supported by another 30,000-plus in Kuwait — on top of continuing Cold War commitments to Germany and South Korea, and to Clinton-era peacekeeping in the Balkans. The Web site maintained by GlobalSecurity.org called “Where are the Legions?” counts 15 of the Army’s 34 active-duty combat units (brigades and regiments) as currently deployed. That means that nearly as many units are abroad as at home, when historical experience shows that a long-term commitment, as with the British in Northern Ireland, requires three or four units recuperating and training for each one deployed.

***

Beyond the extensions of an entire unit’s tour, tens of thousands of individual troops in units slated for Iraq, or in short-staffed specialties, are subject to “stop-loss” orders, which forbid planned departures from the service, even to retire. So far, the overall rate at which Army soldiers voluntarily re-enlist as their terms of service end has stayed stable and on target since 9/11. But recent reporting at bases to which units are now returning from Iraq has showed some alarming drops locally in re-enlistment, particularly among the midcareer sergeants who form the backbone of the Army. “That’s the canary in the mine,” said retired Gen. Robert Scales, former commandant of the Army War College. “The thing that broke the Army in Vietnam was the disappearance of the professional noncommissioned officer corps.”

I’m honestly amazed that it’s taken this long. The military has been ridiculously overstretched for over a decade.

“It is very depressing for a lot of these folks to see that their unit is on the schedule for a second rotation into Iraq,” Raezer said. On the upside, she added, and unlike during Vietnam, “the level of support for the soldiers and their families from civilian organizations, employers [of Guard and Reserve troops], just ordinary Americans, and Congress inspires awe — and it is continuing.”

Another crucial difference is that since Vietnam and the end of the draft, the military has restructured its pay and benefits system specifically to retain the long-serving professionals at the core of the force. The upside is that troops are kept in the ranks by what personnel experts call “the golden handcuffs.” The downside is that personnel costs eat an ever-larger share of the budget. By fiscal 2005, the Congressional Research Service estimates, the cost per service member will be 30 percent higher than it was in 1999.

The upswing dates to the late 1990s. With the federal budget in surplus but recruitment and retention rates worrisomely low, service members’ advocacy groups and the Joint Chiefs of Staff lobbied Congress to fund major new benefits. Troops got bigger housing allowances and automatic annual pay raises fixed at half a percentage point above inflation. Some of the most generous additions were to the retirement plan, including a 25 percent increase in pensions for current troops who serve a full 20 years and an expansion of health benefits for both current and future retirees. Coupled with the same kinds of cost growth as in civilian health care, the new medical benefits caused the Pentagon’s unified medical budget to leap by 25 percent in 2002 alone and to increase at 11 percent annually since, to almost $30 billion in 2004.

Bush inherited, not invented, these exploding benefits. Early in his term, he voluntarily upped military pay even above the automatic increase required by law. But in the fiscal 2004 budget, the White House Office of Management and Budget reined in increases somewhat, and the automatic annual raises are about to expire. Nevertheless, costs continue to rise, especially for health care, where spending will double by 2022, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

We’re in a war without an end in sight. Don’t expect any cuts in the benefits side any time soon.

The military needs more money like the public schools and medicare do–not at all. Nasa spends 400 million on every shuttle launch and some guys in California designed built and flew a space plane for 20 million. Just say no to spending increases guys.

—