Academic Labor Market Exploitation

Atlantic business and economics editor Megan McArdle wonders, “Why Does Academia Treat Its Workforce So Badly?”

Atlantic business and economics editor Megan McArdle wonders, “Why Does Academia Treat Its Workforce So Badly?”

This might seem a ridiculous question, given that most people think professors are overpaid, underworked prima donnas who can never be fired. But she cites Peter D.G. Brown‘s recent Inside Higher Ed piece explaining that, if it was ever the case, it’s not longer true:

As everyone in academe now knows, the professoriate has experienced a radical transformation over the past few decades. These enormous changes have occurred so gradually, however, that they are only now beginning to receive attention. The general public has remained largely unaware of the staffing crisis in higher education. As contingent colleagues around the country came to outnumber the tenured faculty and as they were assigned an ever larger share of the curriculum, they became an inescapable fact of academic departmental life.

Nationally, adjuncts and contingent faculty — we call them ad-cons — include part-time/adjunct faculty; full-time, nontenure-track faculty; and graduate employees. Together these employees now make up an amazing 73 percent of the nearly 1.6 million-employee instructional workforce in higher education and teach over half of all undergraduate classes at public institutions of higher education.

Megan wonders how it came to this, much less why anyone puts up with it, especially given the left-leaning sympathies of the academy which lead one to “assume that the collective preference should result in something much more egalitarian.”

Cato’s Will Wilkinson isn’t surprised. He offers “one multi-part guess: (1) academia is a sticky status hierarchy, (2) academic jobs have a larger consumption component than most jobs, creating (3) increasing rents from tenure.” He explains at length what he means but, in essence, there’s a prestige to the academy that’s reinforced by grad school, this prestige substitutes for other forms of compensation, and the system is controlled by the haves (tenured profs) who would be disadvantaged if they raised the status of the have-not adjucts.

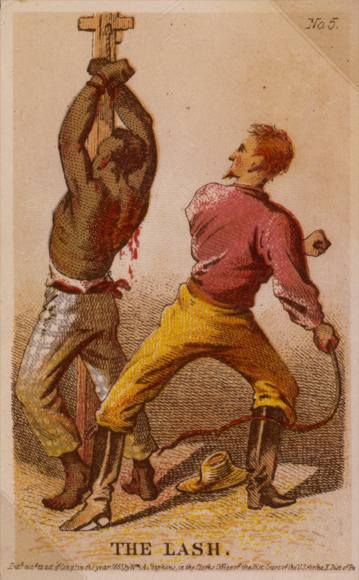

It happens that, way back in January 2006, I wrote a piece for TCS Daily titled “How Wal-Mart is Like Academia,” addressing the issue.

Because the academic market is so tight, universities have adopted virtually the same attitude toward aspiring professors as Wal-Mart does to prospective stockers. They demand heavy teaching loads, substantial committee work, a rigorous pace of professional publication — and offer rather paltry salaries. And that’s for people who have, on average, twenty-two or more years of schooling.

Not only is there intense competition for jobs — a nationwide search and the willingness to move, usually at one’s own expense, to whatever school will hire you is a must — but schools increasingly hire part-timers (called “adjuncts” in the business) who work for peanuts and no benefits rather than full-time professors.

Now, obviously, those who succeed at getting tenure-track teaching jobs make more money and have better benefits than those who land jobs as retail store cashiers. But, then, the latter don’t give up a decade of earnings while pursuing degrees in higher education.

It’s simple supply and demand. There is a vast oversupply of people qualified to teach in most academic disciplines and most institutions are facing budget shortfalls. So, rather than pay, say, $50,000 a year plus benefits to hire a young PhD as a potential lifelong colleague to teach four courses a year (or, eight, in a teaching school) they instead farm those courses out to part-timers for $3000 each. A substantial savings! And there’s a long line of people waiting for the privilege! Why, that’s not exploitation at all!

In slight fairness to my colleagues, there are some faculty who fight these things (I witnessed this firsthand today in a meeting). The private (non-profit) universities I taught at also resisted the use of non-TT faculty other than graduate students, mostly for quality control reasons.

But the train has already left the station in a lot of other disciplines (English is the most egregious example); thankfully in political science, our degrees just aren’t as appealing to wistful slackers avoiding the real world as in the humanities, and political science gen ed isn’t labor/workload intensive enough to create a need for a standing army of low-paid laborers (grad students and adjuncts) to maintain student-faculty ratios: I could teach a 500+-student American government course with no help thanks to Mr. Scantron, but not even the best English professor can effectively teach a 50-student composition course without some help.

And yet, higher education costs outpace inflation. You need to update a post on why college education costs have increased so much. If it isnt going to professor salaries, where is it going?

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/03/education/03college.html

Steve

Another example of colleges becoming more about themselves than the mission to educate. Bloated administration, bloated tenured faculty, bloated classified employee unions. Modern robber barons exploiting the young and parents wanting success for their children.

Granted, I am one the tenured ones (but don’t feel too bloated at the moment), but the point of the post was a decrease in tenure-track faculty and an increase in part-time, cheaper labor.

That would wholly depend on the state. We have no union presence where I teach, for example.

Is this true even in fields where there is demand outside of academia like engineering and accounting; or is it the case only in fields like the humanities where faculty do not have lucrative options outside academia?

A lot of it, especially at state schools, is that the taxpayers have always subsidized tuition at a very high rate. That rate, though, has been steadily decreasing for twenty years. Someone’s got to pick up the slack.

This is exactly right. As states face budget problems, they have to cut back on a variety of things and higher education is one of them and when state funds are taken away the money to pay to run the place has to come from somewhere. Some it comes from hiring the aforementioned adjuncts instead of tenure-track faculty, but most of it comes from hiking tuition.

To tack onto what James and Steven wrote, the answer definitely centers on decreased state contributions. In my state, the state budget for higher education has literally been halved since the 2007-2008 fiscal year. The state’s proposed budget for 2011-2012 rolls back higher ed funding to less than the appropriation for 1986-1987.

And like Taylor, I live and work in a no-union state.