Appeals Court Rules States Cannot Punish ‘Faithless Electors’

The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled last week that states cannot punish electors who fail to follow the will of the majority of voters n their state or state laws purporting to direct how they should vote.

In a ruling released last week, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that members of the Electoral College cannot be legally bound to vote for the winner of their states’ popular vote in a Presidential election:

[A\ federal appeals court has upheld the right of “faithless electors” to vote with their conscience — a ruling that throws into question states’ winner-take-all election systems that bind electors to vote for the state’s popular vote winner, attorneys on Baca’s case said. In a 125-page split opinion Tuesday, a three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit ruled that Colorado’s decision to nullify Baca’s vote and remove him as an elector was unconstitutional.

“The text of the Constitution makes clear that states do not have the constitutional authority to interfere with presidential electors who exercise their constitutional right to vote for the President and Vice President candidates of their choice,” U.S. Circuit Judge Carolyn B. McHugh, an Obama appointee, wrote in the majority opinion, joined by Jerome A. Holmes, a George W. Bush appointee. Mary Beck Briscoe, a Clinton appointee, dissented, arguing the case was moot because no damages could be awarded.

Baca’s attorney, Jason Wesoky, said the ruling essentially makes laws that require electors to vote for the state’s winner unenforceable in Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico. He said the legal team, with attorneys from the group Equal Citizens, is seeking review from the Supreme Court before the 2020 election.

“Certainly the entire point is to get the Supreme Court to address this issue, which has never been addressed on its face before,” Wesoky said.

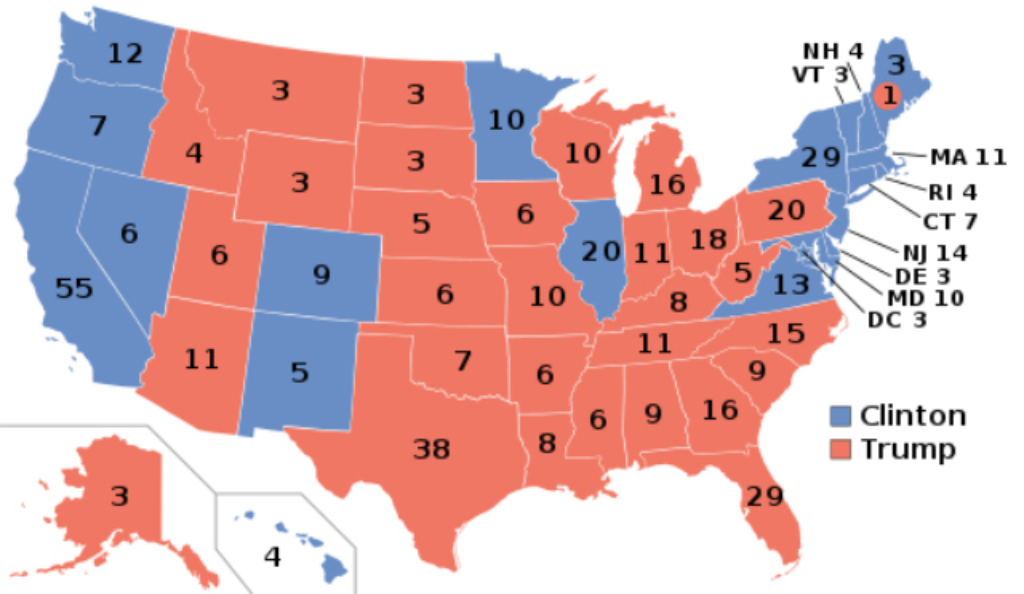

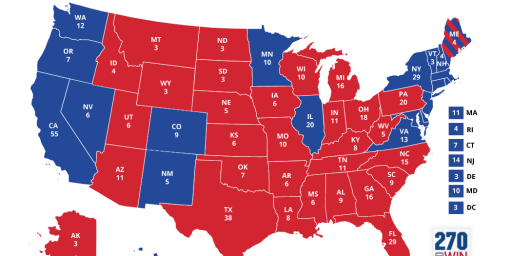

The ruling comes as a growing number of states are rethinking their electoral college systems in response to the 2016 election, after Trump won the presidency despite losing the popular vote by almost 3 million votes. So far, 16 states, including Colorado, have passed laws that would award all of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote — a nationwide initiative that would virtually wipe out the need for an electoral college if enough states join.

It has become a movement embraced largely by Democrats. On Monday, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) called the electoral college a “scam,” a “racial injustice breakdown” that gives more weight to white voters and should be abolished. Democratic presidential candidates including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) andformer Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke have supported scrapping the electoral college as well, pushing for a one-person, one-vote system.

(…)

Baca launched the Hamilton Electors with a fellow elector from Washington state, Bret Chiafalo, after reading Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Paper No. 68. In it, Hamilton lays out his vision for the purpose of the electoral college: a buffer to protect against populism.

The founders were skeptical of direct democracy, fearing it was too vulnerable to electing candidates who knew how to please a crowd but lacked the credentials required for office. The electoral college process, Hamilton wrote, “affords a moral certainty that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.”

But over the years, as the 10th Circuit ruling notes, the electoral college overwhelmingly became a rubber stamp intended to reflect the popular vote in each individual state: As of the 2016 election, 29 states and the District of Columbia had laws binding electors to vote for the state’s popular vote winner.

Baca and Chiafalo thought the 2016 election was the time to return to Hamilton’s vision. Baca viewed Trump as “dangerous” and a “threat to our democracy,” he told The Washington Post.

“We’re trying to be that ‘break in case of emergency’ fire hose that’s gotten dusty over the last 200 years,” Chiafalo told the Atlantic in November 2016. “This is an emergency.”

Baca was told it was a long shot — but he didn’t think so. All they needed was 37 out of 306 Republican electors to vote for a candidate other than Trump, and they also sought out Democrats to vote for moderate Republicans. Baca found two takers in Colorado: Polly Baca (no relation) and Robert Nemanich.

But once that pair saw authorities nullify Micheal Baca’s Kasich vote and refuse to allow him to cast a vote for vice president, they felt forced into voting for Clinton. They were also plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Colorado’s State Department with Baca, but the 10th Circuit ruled they did not have standing Tuesday.

In its ruling, the 10th Circuit said that before this case, it was not aware of any state that had nullified an elector’s vote and removed the elector because it didn’t like his or her vote. The court agreed that there has been a long-standing tradition of electors pledging to vote for their party’s nominee — but there is also “an opposing historical practice at play: a history of anomalous votes, all of which have been counted by Congress.”

As a matter of law, it appears on its face that the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals got this case right and that any laws that purport to restrict how Electors vote in the Electoral College violate the Constitution. In this respect, there are several important facts to keep in mind.

First of all, the Constitution does give states the power to determine who their electors are chosen. While the modern practice has been that electors are selected from slates put forward by the individual candidates and that the slate of the candidate who wins the popular vote ends up being the slate of Electors that meets in December after a Presidential election will match those of the winning candidate, there have been other methods used in the past. For example, at the beginning of the Republic is was common for state legislatures to pick electors without regard to the popular vote. Second, the Constitution also gives the states the power to choose how those electoral votes are allocated. This is why states such as Nebraska and Maine are able to allocate Electors by Congressional District, with the candidate who received the most votes getting the two votes representing the state’s Senators. Third, the Constitution does not require that either the state or the Electors adhere to the popular vote when the Electoral Votes are cast after the Presidential Election. B

Beyond these powers granted to the states, though, the Constitution grants the Electors a wide degree of discretion and does not appear to permit either the states or Congress to restrict the right of Electors to cast their vote as they see fit. This is why we sometimes see a handful of so-called “faithless electors” who cast a vote for someone other than the winner of the popular vote in their state and, often, for someone who is not even on the ballot. In doing so, though, these “faithless Electors” are arguably exercising the kind of independence that the drafters of the Constitution intended when they created the Electoral College.

If this ruling stands, it has several interesting potential impacts that should be of interest to people on both sides of the debate over whether we should keep the Electoral College to begin with. For one thing, it would appear to be a significant set back for the people behind the so-called National Popular Vote agreement under which the states who are a party to the agreement have agreed that their Electors would vote in accordance with the national popular vote rather than the outcome in their particular states. If it withstands Supreme Court review, this ruling would appear to mean that the Electors in NPV states could not be bound by this agreement, which effectively makes the entire agreement pointless. For those who continue to defend the Electoral College, it means that we could see additional cases of faithless Electors, something that could create a Constitutional crisis in the case of an election where the outcome is close in the Electoral College.

It’s unclear, of course, if the losing parties will appeal this decision to the Supreme Court, but given the importance of the issues involved one hopes that they do.

Here’s the opinion:

Baca Et Al v. Colorado Depa… by Doug Mataconis on Scribd

Say one thing for the combination of #TraitorTrump and #MoscowMitch, electing a corrupt, mentally unstable imbecile as president certainly has shown us the holes in the constitution. When this stain is finally scrubbed from the oval office we are going to have to get serious about amending the presidential pardon power, translating the emoluments clause into enforceable legislation and at least begin the process of killing off the electoral college. The constitution is coming apart at the seams.

I think you are overestimating the impact this would have on the NPV compact. The electors are still going to be partisans, selected in advance for their party loyalty. Let’s say, hypothetically, that the compact had been in effect in 2016, and one of the states included in it was Michigan. Even if Trump won a plurality in the state, only the state’s Democratic electors would get sent to vote, due to Hillary’s winning the national vote. They wouldn’t be likely to become faithless electors.

I suppose it would be theoretically possible for faithless electors to affect the outcome under the NPV compact, but it doesn’t strike me as very likely. It would require at minimum that the electoral vote end up very close, despite the popular vote affecting which electors are chosen.

No, I do not hope that the Court, as currently constituted, rules on this.

But it’s an interesting hypothetical. Would Boof and the Boys favor locking in Electors, as their presidential fortunes are better with the antidemocratic EC as is? Or do they oppose, as a barrier to acceptance and implementation of the NPV compact? On it’s face, it’s hard to see which way favors GOPs more.

I’ll also be waiting for further commentary on just exactly what this ruling says. The states must still be allowed to decide who gets on the ballot as an elector. No one’s ever paid much attention to the process, as it’s never really mattered. I believe the parties select the electors and provide the state with a list. If so, could the elector be required by the party, not the state, to enter into a contract to vote as pledged? Are there, perhaps, workarounds for this ruling?

@gVOR08:

The same argument that prevents states from requiring electors to vote for the popularly elected candidate would render such contracts null and void.

Unless the Supreme Court rules otherwise, it will require a Constitutional amendment to abolish the Electoral College.

And when the elector breaches that contract, the party reacts by…

Even simpler than Schuler’s correct observation, once the breach becomes apparent, it’s too late to do anything; the vote has been cast. (Unless the party finds a district court to suspend the election until the tort case can run its way through the Supremes…)

TL/DR: Don’t like the process? Amend the Constitution–it’s the AMERICAN way.