Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Court

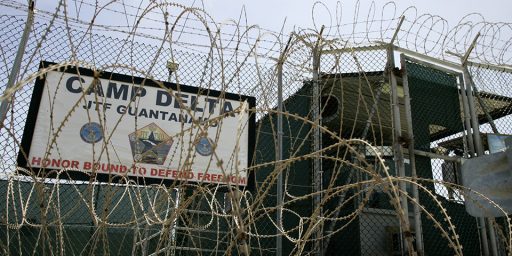

A judge overseeing war crimes cases in Guantanamo Bay has been dismissed from trial without much in the way of explanation.

A judge hearing a war crimes case at Guantanamo Bay who publicly expressed frustration with military prosecutors’ refusal to give evidence to the defense has been dismissed, tribunal officials confirmed Friday.

Army Col. Peter Brownback III was presiding over the case of Canadian detainee Omar Khadr. Marine Col. Ralph Kohlmann, in his role as chief judge at Guantanamo, ordered the dismissal without explanation and announced Brownback’s replacement in an e-mail this week to lawyers in Khadr’s case.

[…]

Charges of conspiracy and supporting terrorism were prepared for Ghassan Abdullah Sharbi, a Saudi with an engineering degree from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University; fellow Saudi Jabran Said bin Qahtani; and Algerian Sufyian Barhoumi. The three are alleged to have attended Al Qaeda training camps and studied bomb-making.

Brownback had threatened to suspend the proceedings against Khadr unless prosecutors handed over Khadr’s medical and interrogation records since his July 2002 capture in Afghanistan.

Khadr’s Navy lawyer, Lt. Cmdr. William C. Kuebler, had asked for the records months ago, and Brownback had ordered the government to produce them.

The lead prosecutor in the Khadr case, Marine Maj. Jeffrey Groharing, this week reiterated to Brownback his view that the defense wasn’t entitled to the records. He urged the judge to set a trial date.

Read the whole thing. Phil Carter has the best analogy for this case.

Imagine if, during the O.J. Simpson murder trial, Judge Lance Ito ordered the district attorney’s office to hand over DNA samples and logs of O.J.’s stay in county jail after his arrest. Then imagine that the prosecutors refused to do so. And that, instead of being fined for contempt of court (or thrown in jail themselves), these same prosecutors somehow got their boss to get Ito tossed off the bench. And then the D.A.’s office worked behind the scenes to replace Ito with a more, shall we say, compliant judge.

Wouldn’t happen. Couldn’t happen. Never in a million years. Not even in California.

Well, Cuba isn’t California, and Guantanamo Bay is further still.

Indeed. I don’t know if Khadr is guilty of the war crimes with which he is charged or not. He may well be. But how can anyone trust the judgment of the court if basic principles of process aren’t followed and if defense attorneys aren’t given access to the evidence necessary to build a case?

Update: In the comments below, Bill Dyer links to this article, giving the Pentagon’s official take on Col. Brownback’s dismissal:

Judge Army Col. Peter Brownback was replaced because his duty orders expire later this month, said Marine Col. Ralph Kohlmann, the chief judge in the U.S. war crimes court at the Guantanamo naval base.

[…]

The Pentagon issued a statement on Friday saying Brownback and the Army had mutually decided he would return to retirement when his active-duty orders expire later this month.

But Kohlmann said in statement on Monday that Brownback had been willing to stay on as long as needed. He said the Army declined in February to extend Brownback’s service “based on a number of manpower management considerations” unrelated to the trials.

Lt. Cmdr. William Kuebler, who is the defense attorney assigned to Khadr, is unconvinced.

Khadr’s lawyer, Navy Lt. Cmdr. William Kuebler, called the explanation “odd to say the least,” given that the Defense Department had recently put out a call urging Navy lawyers to volunteer as judges, prosecutors and defense attorneys in the Guantanamo trials, as a national priority assignment.

I would find it easier to believe the Pentagon were it not for the fact that there are quite a few military lawyers speaking out about the political pressure prizing convictions over process. And even if the Pentagon’s statements are correct, that does nothing to change the fact that the prosecutors in the Khadr case are defying a judge’s orders in refusing to turn incriminating evidence over to the defense so that a proper case can be prepared.

Richard Bacon: Why can’t they be tried in front of a jury in a federal court?

Michael Goldfarb: Well, frankly, there are security issues. You know, we’re not going to expose American citizens to sitting on a jury for al-Qaeda members […]

Richard Bacon: […] So a terror suspect has never been tried in the United States in a civil or federal court?

Michael Goldfarb: Terror suspects have been tried in a federal court …

Richard Bacon: Well, why was that jury exposed to them?

Michael Goldfarb: I mean, if you arrest someone in this country, we’ve dealt with these things differently. The fundamental issue here is that we’re making these things up as we go along. There was no way to do this. […]

Andy Worthington: It’s an extraordinary confession that “we’ve been making this up as we go along.†That’s exactly what seems to have been happening since 9/11 in terms of the detention, interrogation and prosecution of these detainees. You know, what interests me is the issue that you raised of successful prosecutions that took place in the United States of terrorists before 9/11, and this is something that seems to be missed out on, because we’re led to believe that the world started anew on 9/11. Whereas in fact, those of us who have longer memories will remember that there were the African embassy bombings and that there were earlier events, and that there were successful prosecutions.

Richard Bacon: And those juries were exposed to terrorists?

Andy Worthington: Yes, exactly, and it goes deeper than that …

Michael Goldfarb: And that really worked out to prevent 9/11, didn’t it? That really worked out to stymie the onslaught of these terrorists …

Richard Bacon: Are you saying that it somehow contributed to 9/11?

Michael Goldfarb: I’m saying it was an ineffectual response to terrorism, to simply put them in civilian courts and say, “oh, we’re going to treat this as though they’re just criminals like any others.†They’re not criminals like others.

You are assuming that this is an actual court–it is nothing of the sort. This is just representative of Bush’s continual disdain for the law.

This is a military court and subject to military rules. If something illegal has been done please let us know, if not why speculate? I still don’t get why people think we should be prosecuting these people in civilian courts with all the protections we give American citizens. We have an obligation to examine their cases in a manner that determines fact and then the appropriate punishment.

Discovery rules do apply in military courts, you know.

I don’t. I’m fine with courts-martial. But I do expect the UCMJ to be followed, as the law provides.

And how can we do that if prosecutors defy the law, and the judges who so rule are dismissed from those cases?

There might be another side to the story than that which the L.A. Times provides, d’ya think?

This is a military court and subject to military rules. If something illegal has been done please let us know, if not why speculate?

Yes. Speculation is really out of the question.

Those protections aren’t given solely to American citizens, we give them to any person under our legal jurisdiction, citizen or foreigner, legal or illegal.

The only exception we currently have is for detainees in Guantanamo Bay, because while they are under US military detention, the government has declared them outside of US judicial jurisdiction.

There might be another side to the story than that which the L.A. Times provides, d’ya think?

Yes, issues with trials that are explicitly timed for the Nov presidential election certainly have to be presumed innocent.

Gee, Hal, I’m eager to argue with you, but I can’t diagram your sentence.

I’m going to assume, though, that your argument boils down to: Everyone’s innocent except the U.S. government, there’s a conspiracy by Evil BushRoveCo. to persecute these poor peace-loving Muslims, 9/11 was an inside job by the CIA and Mossad, and I’m a right-wing hack for suggesting that it might have been okay for the military to replace a judge who voluntarily retired. Does that save us some time?

but I can’t diagram your sentence

Geebus. Go back to Junior High School, then.

I’m going to assume, though, that your argument boils down to

See, that’s what sleeping during english will do for you.

Does that save us some time?

Not really. All it does is provide a text book example of the way the argument has been waged on the right for the last 8 years.

Bravo.

You realize of course that Alex linked that article in his post?

Again the prosecution denies discovery, the judge order the prosecution to comply, the prosecution refuses, then the judge is scheduled to be replaced despite his willingness to stay on and the severe shortage of people willing and able to do his job.

Another Attorneys site: http://www.tvojklik.com/attorney/

Hal, Michael and Triumph seem to like the Nation’s analysis of these issues.

Their approach is somewhat at odds with historical precedent in times like these when our nation has been subject to unconventional warfare attacks at home and abroad.

That is when military commissions have traditionally been used. Military commissions are neither invented by nor unique to the “Bush Administration”, see, e.g., ex parte Quirin.

Money Quote:

Well, stepping back, I’ve long been of the opinion that this is not a war, it is a police action. There is no country, and anything in the past has been based on such an assumption. Take away the country and you are left without the current framework of rules that we have operated with in the past. Framing it as a war is extremely problematic and the consequences of this ill advised framing are quite apparent to even the initial skeptics.

Having said that, the point is simply that even within a military tribunal – regardless of whether you hold my view of the affair, or Michael Goldfarb and Bill Kristol’s view of what this struggle is all about – there are rules to be followed. The issue is that, even within the framework of a military tribunal, such rules are not being followed. Worse, the issue of the judge which is what this post is about make the whole process seem more of a joke rather than anything useful.

Even in war, there are standards to be followed – or, used to be.

Geeez….

I have, for the defenders of this “process”, a simple question:

Who among you are willing to be prosecuted, even for a crime as simple as jay-walking, under these rules?

Who? Who? Any takers? No caveats, now… Just who is willing?

I don’t see it that way, Hal. But reasonable people can differ.

The overt hostility characterized by the spectacular tactics like the Khobar Towers, the USS Cole, and the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington, DC were more than mere criminal activities. All of these events seemed to me to more seriously jeopardize the nation’s safety than the organized drug trade, the mafia, or other international crime syndicates.

If any rules and procedures are breached in the military tribunal, the alleged offenders have appellate rights that can correct any prejudicial breaches.

One thing for sure, there are very competant and committed defense counsel representing the accused in these proceedings at no expense to them.

If BHO wins the election, as is distinctly possible, it will be interesting to see what he does with these folks, and what the results will be during his watch.

Then we can compare and maybe contrast.

We shall see.

They aren’t accused of jaywalking, tom p. They are accused of violating the laws of war. As the above quote from the Quirin case shows, military commissions are appropriate for individuals so accused.

vnjagvet,

Wouldn’t precedent require that the detainees be classified as POWs? Also, I’m pretty sure we don’t have any national historical precedent for the kind of war we’re fighting, unless we go back to the days of fighting piracy in what, the late 1700s?

Hal,

There weren’t always countries, we have historical wars between ethnic groups, city states, etc. Even in US history we have the piracy wars I mentioned above, the Civil war, and numerous native American wars where there was not clearly defined “country”.

There weren’t always countries, we have historical wars between ethnic groups, city states, etc. Even in US history we have the piracy wars I mentioned above, the Civil war, and numerous native American wars where there was not clearly defined “country”

Yes, I understand that. We’ve also had quite a bit to do with organized crime and drug cartels which seem every bit as nasty as terrorists. Not to mention white christian separatists, christian militias, etc.

And the question is, what did we do in these cases? Did we try Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols as enemy combatants in a military court? Of course not. What about dealing with Waco or Ruby ridge? How did we defeat the mob? What about the mexican drug cartels?

Are we just going to have to make Guantanamo a heck of a lot bigger? Start chucking the criminal court system, bring in the military and treat it like we’re fighting countries?

Somehow I don’t think that’s even close to the correct answer. Sure, the military is a component, but I would argue that it’s not even a *major* component in the issues with non-state actors.

Even terrorists. Certainly not for countries which weren’t even terrorist countries before we invaded them, to be sure…

In those cases, these groups were inside the US, under the jurisdiction of civilian law enforcement*. Not so with Al Qaeda militants in Afghanistan and Iraq.

That wasn’t ever my position, I was merely pointing out that history provides examples of war conducted against non-nation states.

(*)I’m not familiar with the Mexican drug cartels, but I don’t think we’ve been able to do much in the way of combating them with law enforcement initiatives.

I don’t think we’ve been able to do much in the way of combating them with law enforcement initiatives.

A point not lost on the civil libertarians…

I don’t think we’ve been able to do much in the way of combating them with law enforcement initiatives.

… and, I would point out, that we don’t seem to be able to do much in the way of combating them with military initiatives, either.

I don’t believe the Mexican drug cartels have had the privilege of facing the full might of the United States Armed Forces, but if they ever did I don’t believe they will fare as well as they have against law enforcement.

I don’t believe they will fare as well as they have against law enforcement.

Hmmm. Certainly not the *full* might of the US armed forces, but then there’s that problem of the mexican civilians, not to mention the pesky mexican government which would make such fantasies extremely complicated. Still, one only has to look to the booming success of the Columbian cartels to get a hint as to how the military biased strategy have worked out so far.

Michael:

There was little question that beginning at least in September 2001, Bin Laden and Zawahiri, with the aid and encouragement of the Taliban in Afghanistan, escalated their campaign of terrorism by attacking the US. The individuals who aided and abetted the attackers, saboteurs all, are equally guilty of sabotage. Sabotage is a violation of the laws of war.

When the US went after those aiding and abetting the saboteurs in Afghanistan, it believed it caught some. Those make up one group of Guantanamo prisoner being tried by Military Tribunal.

During the war in Afghanistan, we captured individuals on the battlefield who were engaged in a number of nefarious activities believed by the capturers to be violative of the laws of war(e.g., not readily or distinctively identified as combatants). These folks are another group of Gitmo prisoner subject to military tribunal.

The third group in Gitmo are, in fact, prisoners of war. They are being held in accordance with the Geneva Convention. Until hostilities are over, they need not be released. Unless they participate in crimes while POWs, however, they are not subject to proceedings by military tribunal.

Hal:

No one has ever suggested that there was much evidence that McVeigh or Nichols were working for another country or group or organized terrorists seeking to overthrow the government. Bin Laden never has made any bones either about the purpose of his jihad against the US or about the role of the 9/11 attacks in it.

Criminal syndicates are clearly out there to make money from their enterprises, not to overthrow governments.

Grewgills asked (at 2:22pm), in response to my assertion (at 11:58am) that there might be another side to the story and my link to a later news article, “You realize of course that Alex linked that article in his post?” Yes, I’m grateful that after my comment and its embedded link, Alex updated his original post. The update isn’t marked to show its time, but Alex duly credited my comment as having inspired it. That’s because Alex is a straight-up and intellectually honest guy, which is a key reason that I enjoy debating issues with him, in absolute good faith, on this blog. (Ditto for Dr. Joyner and their co-bloggers.)

Tom p asked (at 7:12pm): “Who among you are willing to be prosecuted, even for a crime as simple as jay-walking, under these rules?” Well, I’m not eager to be charged with any crime, but whether it were jay-walking or murder, I’d much rather be tried by one of these commissions than by the regular criminal courts of most other countries other than the U.S. The procedural rights accorded to the accuseds in these proceedings aren’t as extensive as they are for regular criminal trials inside the U.S., but they are better than what’s available in many, many other supposedly civilized countries. (Contrast, e.g., all countries whose criminal systems stem from the Napoleonic Code, in which there is no presumption of innocence!) Moreover, I personally would much rather risk my life on the relative degrees of corruption vs. integrity in the U.S. military than I would on the judicial systems of most other countries (including places like Spain, Italy, Japan, or even Canada).

It’s fine that there are skeptics. When a judge is taken off a case, it’s fine that someone asks “Why?” But when there’s a clear answer that doesn’t smack of anything improper — as here, where the judge is, by his own decision and agreement, going off the active duty status that he’d need in order to preside — then only hard-core conspiracy theorists will continue to insist that this incident shows some lack of fairness.

As for the pending ruling on production: I don’t know whether departing judge Brownback’s interim ruling is correct or incorrect. I can’t tell from these stories, and I don’t know, whether the commission’s tribunals permit interim challenges to trial judge rulings on producing evidence. It may be that the prosecution is seeking immediate review prior to complying, and that may be entirely proper. Even if not, however, presumably that’s a potential appeal point for this defendant; if the prosecution chooses to run the risk of noncompliance, they do so knowing that creates a vulnerability on appeal. And even that presumes that Judge Brownback’s successor lets the trial proceed notwithstanding their noncompliance. Instead, it’s entirely possible that he may agree with Judge Brownback, and condition holding the trial on the prosecutors’ compliance. In that event, there would likely be a dismissal, from which the prosecutors would appeal. Bottom line, anyone whose knickers are seriously twisted by this interim evidentiary ruling is ignoring the bigger picture and drawing vastly premature conclusions.

The outcomes of these trial are not foregone conclusions by any means. Congress defined the playing field (including the factors affecting its slope), but these are incredibly challenging prosecutions even apart from the self-imposed handcuffs that may be imposed by national security concerns. I’ll be surprised, for example, to see this defendant get the death penalty, if for no other reason than that he was a minor when he was captured.