Bart Starr, Winning Quarterback In First Two Super Bowls, Dies At 85

Bart Starr, who led the Green Bay Packers to five N.F.L. Championships in the pre-Super Bowl era and in Super Bowls I and II, has died at the age of 85.

Bart Starr, the N.F.L. Hall of Fame Quarterback who led the Green Bay Packers to wins in the first two Super Bowls as well as five N.F.L. Championships in the pre-Super Bowl era, has died at the age of 85:

The Packers, of course, are memorializing Starr:

Bart Starr, the first quarterback in history to win five National Football League championships and hero of the most memorable game in the storied history of the Green Bay Packers, died today in Birmingham, Ala.

He had been in failing health since suffering a serious stroke in 2014.

Starr, 85, played for the Packers from 1956 to 1971, and was beloved by fans of not only his generation, but also succeeding ones. Along with being a Pro Football Hall of Famer and among a small pantheon of Packers’ all-time greats, he was the franchise’s nonpareil role model in the eyes of many.

Maybe the most popular player in Packers history, Starr will be eulogized for being a consummate professional, a Good Samaritan and an exemplary role model.

“The Packers Family was saddened today to learn of the passing of Bart Starr,” said Packers President/CEO Mark Murphy. “A champion on and off the field, Bart epitomized class and was beloved by generations of Packers fans. A clutch player who led his team to five NFL titles, Bart could still fill Lambeau Field with electricity decades later during his many visits. Our thoughts and prayers go out to Cherry and the entire Starr family.”

As a player, Starr will be remembered for being the only quarterback ever to lead his team to five NFL titles in a decade and for that frozen-in-time moment where he was lying face down under a pile of bodies in the south end zone of Lambeau Field, the hero of the Ice Bowl.

To this day, a half-century later, Starr’s game-winning quarterback sneak in that Dec. 31, 1967, game remains the signature moment in Packers history and personified what the Packers franchise is all about: Perseverance against all odds and unmatched success among all NFL teams.

With the Packers trailing by three points, 16 seconds remaining and the ball at the 1-yard line, it was Starr who suggested to coach Vince Lombardi during the Packers’ final timeout that he run a quarterback sneak for the first time that season.

When Starr squeezed between the blocks of right guard Jerry Kramer and center Ken Bowman and landed in the end zone, he not only sealed the Packers’ 21-17 victory over the Dallas Cowboys, but also climaxed the Lombardi Era.

What made it such a timeless moment in pro football history besides the last-minute drama were the conditions – a frozen field, temperatures that hovered around -16 degrees and a brutal wind chill that dipped to a -46 – and the stakes

To this day, the Lombardi Packers are the only team to win three consecutive NFL titles since post-season play was introduced 85 years ago.

Starr’s name may have been the most flamboyant thing about him. But he would prove to be skilled, sly and, by at least one measure, incomparably successful: He won five N.F.L. championships (in 1961, ’62, ’65, ’66 and ’67), and the first two Super Bowls, in 1967 and ’68. (With his victory in 2019, Tom Brady has won six Super Bowls.)

The Packers, with Starr at quarterback, won three straight N.F.L. championships, a run that helped bring new attention to professional football as it moved into the Super Bowl era.

He was named the league’s most valuable player in 1966 and received the same honor in Super Bowls I and II. He was selected to the Pro Bowl four times. And on a team known for running — with the flashy Paul Hornung and the rugged Jim Taylor — Starr was one of the league’s most efficient passers. He led the N.F.L. in that crucial category in three seasons and, on average, for all of the 1960s — even though his rival Johnny Unitas of the Baltimore Colts was often viewed as better.

He set career records for completion percentage, 57.4, and consecutive passes without an interception, 294.Those records were eventually broken in a league transformed by precision passing offenses and increasingly coddled quarterbacks, many groomed since childhood and arriving at the annual N.F.L. draft as celebrities. Starr, by contrast, was drafted in the 17th round in 1956 after barely playing his senior year at Alabama, and he may not have been the most talented player on the Packers during their glory years. Many teammates from that era — including Hornung, Taylor, Willie Davis, Forrest Gregg, Jerry Kramer and Ray Nitschke — are in the Hall of Fame.

Yet Starr became the Packers’ most essential player. Lombardi was a new kind of coach — comprehensive, obsessive, relentless — and he needed a new kind of quarterback, serious and studious enough to put his grand plans into motion, to make crucial decisions when the game, and maybe the season, was on the line and to endure his sometimes harsh criticism. Starr became a passionate student and a superlative field general, and he never stopped giving Lombardi credit for his success.

“I loved it,” he recalled in David Maraniss’s 1998 book, “When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi.” “I loved the meetings. I never, ever was bored or tired at any meeting we were in with Lombardi. I appreciated what he was trying to teach. He was always trying to raise the bar.”

Even as Lombardi wrote the script, Starr directed the offense, calling the plays. His most memorable was his boldest.

It happened in the frigid twilight at Lambeau Field in Green Bay, Wis., on Dec. 31, 1967, in the conference championship game between the Packers and the Dallas Cowboys, now known as the Ice Bowl. The temperature was 13 degrees below zero, and a new heating system installed beneath the turf had failed. Players slipped and fell all afternoon. Starr fumbled disastrously, leading to a touchdown for Dallas.

With less than five minutes to play, the Packers trailed, 17-14, with nearly 70 treacherous yards between them and the end zone. Mixing short passes with run plays, Starr calmly marched his team within two feet of a touchdown. But in the final minute, the Cowboys twice stopped the Packers when they tried to run the ball into the end zone. Sixteen seconds remained when Starr called a timeout and walked to the sideline to confer with Lombardi.

There was no talk of kicking a field goal to tie and force overtime. As Lombardi later recalled, he was worried that Green Bay’s benumbed fans could not endure an extra period. Starr told the coach that the running backs were struggling to get traction, but that he thought he could sneak the ball across the line himself.

“Then run it!” Lombardi told him. “And let’s get the hell out of here!”

Starr returned to the huddle and called for a run play without telling his teammates that he intended to keep the ball.The ball was snapped. Starr hesitated for the slightest moment. Then he dove into the end zone behind big blocks by Jerry Kramer and Ken Bowman. The Packers won, 21-17.

“Texas has the lone star,” read a homemade sign in the stands, “but we have the bright Starr.”

Two weeks later Green Bay defeated the Oakland Raiders, 33-14, at the Orange Bowl in Miami in Super Bowl II. It was the final championship for the Starr-Lombardi Packers. Lombardi resigned as coach and became general manager in February 1968, joined the Washington Redskins as coach and part-owner a year later, and died of cancer in 1970.

(…)

Bryan Bartlett Starr was born on Jan. 9, 1934, in Birmingham, the eldest of two sons of Ben Starr and Lulu (Tucker) Starr. Starr’s father, who was of Native American lineage, served in the National Guard before establishing a career in the Air Force and settling his family in Montgomery, Ala.

Ben Starr believed that Bart’s brother, Hilton, who was two years younger and known as Bubba, had more athletic potential, and he often said so to Bart. When Hilton was 11, he cut his foot on a dog bone while walking barefoot. Three days later he died of a tetanus infection. His death devastated the family, and Bart Starr would later say that it put more distance between him and his father.

When Starr was a junior in high school and playing for the varsity squad, he became the starting quarterback only after the coach’s first choice was injured. But he led the team to an undefeated season and as a senior was heavily recruited.

He nearly chose to attend the University of Kentucky, where the celebrated Bear Bryant was coaching at the time. Instead, to be close to his girlfriend, Carol Morton, he accepted an offer from Alabama. Starr married Ms. Morton in 1954, after his sophomore year.

Playing under Red Drew, Starr became the starter as a sophomore and led the Crimson Tide to the Cotton Bowl. But he missed nearly all of his junior season with a back injury and was then demoted to a backup role as a senior under a new coach. When the 1956 draft arrived, Jack Vainisi, the personnel manager for the Packers, decided to take a chance on Starr, though not much of one: The Packers made Starr the 199th college player chosen in the N.F.L. draft.

Starr floundered in his early years in Green Bay. Then Lombardi arrived. After a few stops and starts, Starr became the starter for good in 1960.

As his star rose on the field, the public began seeing what Lombardi saw: a loyal, dependable leader who worked hard away from the game as well. Unlike many of his teammates, Starr lived year round in Green Bay, where he received “Mr. Nice Guy” awards from community groups — a label that frustrated him but that he never risked contradicting. In 1965 he helped found the Rawhide Boys Ranch, a faith-based nonprofit residential care center for at-risk youth.

Here’s video of that famous Ice Bowl game-winning Quarterback sneak:

And a longer video about the Ice Bowl:

Outside of Green Bay, Starr wasn’t much of a presence in the NFL after retirement, but that didn’t stop him from being remembered. I was born after the Ice Bowl, and after the end of the Lombardi/Starr era, but even I knew who Bart Starr was. The last time I saw him in public was several years ago during a Sunday night N.F.L. game during which the Packers were retiring the number of fellow Packer Brett Favre. Starr had reportedly been ill the week before the game and there was some question if he would attend the ceremony as he typically did when the Packers had a special ceremony like that, but he managed to make it there notwithstanding the fact that it was a cold and bitter evening at Lambeau Field. The cheers from the crowd made it seem like it was 1967 again, but that’s not surprising because Packers fans are particularly well-known for their love for the team and their nostalgia. (You can watch the video of that moment on YouTube) In any case, Starr was obviously one of the greatest players of his generation. Where that places him now after the Quarterbacks that have followed in his footsteps is something that fans will be debating for years to come, no doubt.

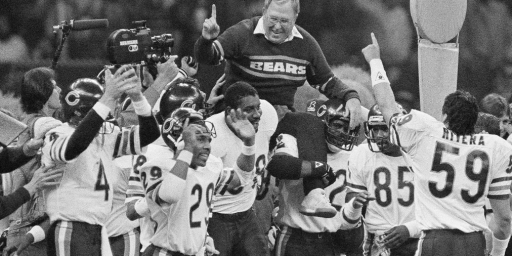

RIP Bart Starr from a die hard Bears fan.

Bart Starr 15-9 as QB vs Bears.

Bart Starr lived a life of achievement and athletic glory; he had many honors bestowed on him. He was seen as an examplar of traditional American values at a time when those values were being challenged. I remember when Joe Namath was being unfavorably compared to Bart.

It is interesting that the recent death of Murray Gell-Mann has gone with much less notice.

I don’t wish to imply any disrespect for Mr. Starr. I was also a Bears fan during that era and can’t entirely shed my prejudices.

@Slugger:

This is the first I hear of it, and I do follow a few science websites.

There is a Skeptical Inquirer post on my Facebook feed timestamped 10 hours ago that notes Murray Gell-Mann’s death occuring May 24th.

I saw that after I read Slugger’s comment here on OTB. My primary source of news.

I am curious to find out where and when Slugger saw this notice.

Six degrees of separation. Benedict (Ben) Gelman, Murray’s brother, was an editor for the Southern Illinoisan newspaper here in Sleepytown for several years. I never met Ben however the brother of a friend of mine was acquainted with both of them.

For what it’s worth.

I met Starr playing golf some 20ish years ago. Surprisingly quiet and reserved. Nice guy.

Go Bears.

@Mister Bluster: Ben and Murray did some bird watching in a documentary about Murray a few years ago, and Murray says it was actually Ben’s copy of Finnegan’s Wake where the word quark came from.