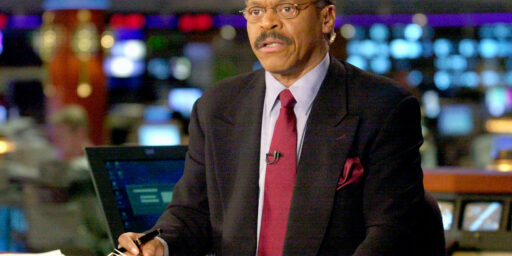

BEING AN ANCHORMAN

NYT prints an excerpt from a forthcoming book by David Brinkley, who died Wednesday at the age of 82. He offers some candid observations on the evolution of network news, especially the anchorman, and argues that neither are as powerful as most think. The irony is that, with the rise of cable news outlets and the Web, this has become especially true. Many of us who once upon a time would never miss the nightly news now seldom watch it, getting our information when we want it, where we want it.

The entire piece is pasted in the entended entry, since NYT columns have a habit of disappearing into the archives (and are inaccessible without registration).

June 14, 2003

On Being an Anchorman

By DAVID BRINKLEY

When they learned how to send pictures through the air, out came a new creature called the anchorman. God knows where that term originated. Some of us who have held the position have never liked it, but there it is.

The anchor’s role is difficult to assess, because there is nothing to compare to it. Newspaper reporters and editors do some of the same work, but they are not more or less personally in the living room every night and are not instantly recognizable in airports, poolrooms and saloons.

But the great difference, I think, is that in a night-to-night or day-to-day relationship with tens of millions of people, the anchor gives the news a kind of dimension and character it never had before, mediated through his own voice and appearance and personality. The news then becomes not just what happened but what a familiar face and voice says happened, and the meaning of it is to some extent determined by how he says it.

It is a strange relationship, and only a few people have experienced it in the half century or so since television news became a significant force in American life. Between the anchor and the audience, there is a kind of intimate remoteness. They know his clothes and his haircuts and to some extent his likes and dislikes. They watch him get older. They feel they know him, and in a way they do. But he does not know them.

By now, it has become accepted as journalism. But it bears only a scant relationship to the journalism we knew in the past — and still know in news media other than broadcasting. Television news is not merely the same news delivered in a different way. It is different because the means of its delivery changes its meaning to its audience and because it reaches more, and different, people — many of them barely, if at all, reached by other news.

It might be politically dangerous for any one person to have that much access to so many eyes and ears. But as our own politicians have lately discovered, the American people tend to believe little of what they hear from their government; they tend to assume that whatever they are told by political leaders is a pack of lies. And as we have seen, and continue to see, remarkably often they are right. To some degree, the same is true of journalists, and television journalists in particular. Delivering the news on television is not unlike appearing on the stage of a provincial Italian opera house. When the aria is over, nobody knows if the reaction will be cheers and applause, or cabbage and tomatoes, or both.

In my view, television news tends more to reinforce the existing social and political values than to change them, and the recurring cry that it and other news media excessively influence public opinion in one political direction or another seems to me an empty claim. It must be if, after a half century of news reporting that has been regularly charged with being too liberal, we have recently elected some of our most conservative presidents.

TV anchors and reporters serve the useful public function of delivering the goods, attractively wrapped in the hope of attracting some millions of people to tune in. In recent decades, I fear, the wrapping has sometimes become too attractive and much television news, in response to economic pressures, competition and perhaps a basic lack of commitment to the integrity and value of the enterprise, has become so trivial and devoid of content as to be little different from entertainment programming. But even at its best, television news is driven less by the ideology of those who deliver it than by the pressures of the medium itself. And as a result, individual journalists, from the anchors to the local news beat reporters, are all constrained in their power by the skepticism of a public that from the beginning saw in television something closer to the tradition of entertainment (movies, theater and the like) than to the tradition of the press.

The television journalist does have the power to steer the public’s attention in one direction or another. He can make an obscure person famous for a day or two, but not much longer than that, unless the person is then able to hold the public’s attention with his own resources. Television can keep a story alive but it cannot ensure that the public will continue to believe in it. The year or more during which the news media was obsessed with the Monica Lewinsky scandal, for example, saw a significant rise in President Clinton’s public approval ratings and a significant decline in the media’s.

There is no question that television anchors have become enormously famous. Most of my adult life has been shaped by that reality. But I do not believe that I, or my fellow anchors, have become famous for our power to influence uncritical masses of people, or for our ability to change the social or political order, or to elect a candidate or defeat one. So what are we famous for? Mainly, we are famous for being famous.

To survive, an anchor must convince millions of people that he is at least modestly competent, that he has some idea of what he is talking about, and that he is playing it straight, and that is about all. He might also wear a tie and keep his suits pressed and comb his hair if he has any (and virtually all anchors have quite a lot).

I believe that all of the network anchors of my time have done that pretty well, and I tried to do the same. But is there any real power? I believe not. Over the years, several television newsmen, not understanding that they were famous only for being famous, have run for political office. Most of them lost.

It has been at least 5 or 6 years since I made a habit of watching the network news, and only watch it now either by accident, or when channel-surfing during a major news event.

As an aside, not only do the NYT archives disappear behind a wall, but mere registration has disappeared as the means of access to the archives; if you want an archived article, you must pay [even thought they say it as an “invitation”].

—