Sex Retalliation Cases Allowed

The Supreme Court ruled that those fired for complaining about illegal sex discrimination may sue the employer who fired them.

School officials may sue under a federal civil rights law when they suffer retaliation for complaining about discrimination against girls’ sports teams, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled. The justices, voting 5-4, reinstated a lawsuit by an Alabama high school girls’ basketball coach who was stripped of his duties after objecting that his team had to use inferior equipment and facilities. The court also said that victims of bias themselves can sue for retaliation.

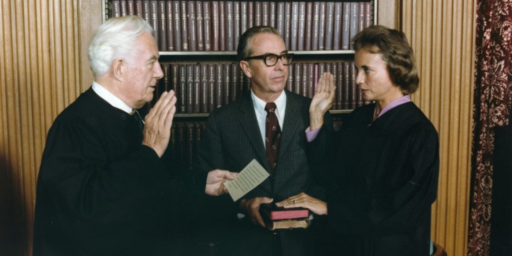

The ruling strengthens a 1972 law that bars sex bias in federally funded education, opening the door to potentially thousands of retaliation suits a year. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission received more than 22,000 retaliation complaints under U.S. civil rights laws in its last fiscal year. “Without protection from retaliation, individuals who witness discrimination would likely not report it, indifference claims would be short-circuited, and the underlying discrimination would go unremedied,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote for the majority.

Well, no kidding. The Supreme Court takes roughly 85 cases a year. Something this obvious should not have to be among them.

The appeals court said Title IX doesn’t let people sue over retaliation for complaints about violations of the law. In addition, the court said Jackson couldn’t sue because he didn’t suffer sex discrimination himself. The language of the law prohibits “discrimination” against any person “on the basis of sex.” The statute says nothing about retaliation.

Even though Alabama is an “employment at will” state, one wonders why such cases couldn’t be brought under standard wrongful termination grounds.

Update (1252): NYT has a better synopsis of the case: Justices Expand Discrimination Protections Under Title IX Law

…[A] crucial question that had been unanswered, until today, was whether by extension Title IX protected people who complained about sex discrimination against others, then suffered retaliation for their complaints. Since 1975, the federal government has interpreted Title IX as providing protection against retaliation – even though the statute itself does not mention retaliation, unlike some other civil rights laws. Justice O’Connor concluded that if the law were found not to protect retaliation, its very purpose would be undermined because “individuals who witness discrimination would be loathe to report it, and all manner of Title IX violations might go unremedied as a result.” Joining her in the majority were Justices John Paul Stevens, David H. Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen G. Breyer.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a dissent that was joined by Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony M. Kennedy. Asserting that “retaliatory conduct is not discrimination on the basis of sex,” the dissenters said the majority was going against the court’s own precedents. “We require Congress to speak unambiguously in imposing conditions on funding recipients through its spending power,” Justice Thomas wrote.

[…]

Alabama’s solicitor general, Kevin C. Newsom, countered that Mr. Jackson could take his complaint to the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights if he wanted, and that “Title IX’s remedial apparatus is ticking along just fine.” Justice Ginsburg asked just how often the Office of Civil Rights had investigated complaints in Birmingham. Twice in 20 years, a lawyer for the Birmingham school board replied. “Two in 20 years?” Justice Ginsburg replied, perhaps tellingly.

Of course, one wonders how often complaints were made. Two investigations is great if there were only two complaints; not so much if there were 2000.

Update (1430) Juan Non-Volokh points to the opinion by O’Connor and dissent by Thomas (PDFs both) and links some background information. The lead-in to the dissent makes sense to me:

The Court holds that the private right of action under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, for sex discrimination that it implied in Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U. S. 677 (1979), extends to claims of retaliation. Its holding is contrary to the plain terms of Title IX, because retaliatory conduct is not discrimination on the basis of sex. Moreover, we require Congress to speak unambiguously in imposing conditions on funding recipients through its spending power. And, in cases in which a party asserts that a cause of action should be implied, we require that the statute itself evince a plain intent to provide such a cause of action. Section 901 of Title IX meets none of these requirements. I therefore respectfully dissent.

Hard to argue with that. I agree with the result reached by the majority and even their rationale that protection for whistleblowers is necessary to give teeth to the legislation. But it does seem like a leap from that to simply declaring something not in a law to be in the law. O’Connor’s rationale (p.4) is rather thin:

Retaliation against a person because that person has complained of sex discrimination is another form of intentional sex discrimination encompassed by Title IX’s private cause of action. Retaliation is, by definition, an intentional act. It is a form of “discrimination” because the complainant is being subjected to differential

treatment.

I don’t doubt that retaliating against whistle blowers is a form of discrimination. Hell, so is preferring people with a college degree or those without a criminal record. But Title IX prohibits only discrimination on account of sex. It’s rather hard to see how that was the case here–although, granted, that’s a question of fact may well result from adjudication.

The legal issue from this case stemmed from the fact that the coach, who is male, was not actually being discriminated against. So the legal issue was whether the coach had standing to sue under the law.

Alex,

Gotcha. It’s not clear to me why he needed to sue under Title IX.

James — I’m not sure he would have a wrongful discharge claim under state law. He might, but it’s not necessarily the case.

Also, I’m pretty sure that under Title IX the court can award attorney fees to the prevailing party. I would guess that does not happen under Alabama state law. Again, just a guess.

Finally, this is probably a case where a plaintiff would rather be in federal court than in the local district court. Since there would be no diversity of citizenship, the only way to get into federal court is to have a federal cause of action.

Sounds like finding something in the law that wasn’t.

Also, you would think there would be other ways he could seek relief-wrongful termination, maybe under the whistleblower law.