China Losing Patience With Pyongyang? Don’t Believe It Until You See It Happen

There are again reports of Chinese frustration with the Kim regime in North Korea, but change is unlikely to happen in the DPRK until Beijing is ready to let it happen.

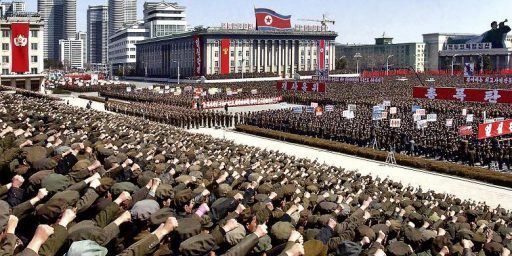

With world attention focused yet again on Pyongyang thanks to U.S. Government claims that the modern day Hermit Kingdrom is behind the cyber attacks on Sony Pictures over the release of a move that depicts the assassination of Kim Jong Un, we’re once again seeing reports that the Kim regime’s sponsors and protectors in Beijing may be growing frustrated with them:

BEIJING — When a retired Chinese general with impeccable Communist Party credentials recently wrote a scathing account of North Korea as a recalcitrant ally headed for collapse and unworthy of support, he exposed a roiling debate in China about how to deal with the country’s young leader,Kim Jong-un.

For decades China has stood by North Korea, and though at times the relationship has soured, it has rarely reached such a low point, Chinese analysts say. The fact that the commentary by Lt. Gen. Wang Hongguang, a former deputy commander of an important military region, was published in a state-run newspaper this month and then posted on an official People’s Liberation Army website attested to how much the relationship had deteriorated, the analysts say.

“China has cleaned up the D.P.R.K.’s mess too many times,” General Wang wrote in The Global Times, using the initials of North Korea’s formal name, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. “But it doesn’t have to do that in the future.”

Of the government in North Korea, he said: “If an administration isn’t supported by the people, ‘collapse’ is just a matter of time.” Moreover, North Korea had violated the spirit of the mutual defense treaty with China, he said, by failing to consult China on its nuclear weapons program, which has created instability in Northeast Asia.

The significance of General Wang’s article was given greater weight because he wrote it in reply to another Global Times article by a Chinese expert on North Korea, Prof. Li Dunqiu, who took a more traditional approach, arguing that North Korea was a strategic asset that China should not abandon. Mr. Li is a former director of the Office of Korean Affairs at China’s State Council.

In a debate that unfolded among other commentators in the pages of Global Times, a state-run newspaper, after the duel between General Wang and Mr. Li, the general’s point of view — that North Korea represented a strategic liability — got considerable support. General Wang is known as a princeling general: His father, Wang Jianqing, led Mao Zedong’s troops in the fight against the Japanese in Nanjing at the end of World War II.

Efforts to reach General Wang through an intermediary were unsuccessful. The general’s secretary told the intermediary that the views in his article were his own and did not reflect those of the military.

How widespread his views have become within the military establishment is difficult to gauge, but a Chinese official who is closely involved in China’s diplomacy with North Korea said that General Wang’s disparaging attitude was more prevalent in the Chinese military today than in any previous period.

“General Wang’s views really reflect the views of many Chinese — and within the military views are varied,” said the official, who declined to be named because of the sensitivity of the matter. Relations between the North Korean and Chinese militaries have never been close even though they fought together during the Korean War, the official said. The two militaries do not conduct joint exercises and remain wary of each other, experts say.

l, the parlous state of the relationship between North Korea and China was on display again Wednesday when Pyongyang commemorated the third anniversary of the death of Kim Jong-il, the father of the current leader, Kim Jong-un, and failed to invite a senior Chinese official.

The last time a Chinese leader visited North Korea was in July 2013 when Vice President Li Yuanchao tried to patch up relations, and pressed North Korea, after its third nuclear test in February 2013, to slow down its nuclear weapons program.

Mr. Li failed in that quest. The North Korean nuclear program “is continuing full speed ahead,” said Siegfried S. Hecker, a professor at Stanford University and former head of Los Alamos National Laboratory. North Korea had produced enough highly enriched uranium for six nuclear devices, and it may have enough for an additional four devices a year from now, an assessment the Chinese concurred with, Dr. Hecker said.

After the vice president’s visit, relations plummeted further, entering the icebox last December when China’s main conduit within the North Korean government, Jang Song-thaek, a senior official and the uncle of Kim Jong-un, was executed in a purge. In July, President Xi Jinping snubbed North Korea, visiting South Korea instead. Mr. Xi has yet to visit North Korea, and is said to have been infuriated by a third nuclear test by North Korea in February 2013, soon after Kim Jong-un came to power.

Though they have not met as presidents, Mr. Xi was vice president of China and met Mr. Kim when he accompanied his father to China, several Chinese analysts said.

What happened in that exchange is not known, but Mr. Xi, an experienced and prominent member of the Chinese political hierarchy, was unlikely to have been impressed with the young Mr. Kim, who at that stage was not long out of a Swiss boarding school, the analysts said.

“It’s very obvious that there is a very significant change in attitudes,” said Deng Yuwen, a former deputy editor of Study Times, the Central Party School journal, who was dismissed in early 2013 for writing a negative piece about North Korea.

In a sign of more public questioning about North Korea, Mr. Deng, who went to Britain after losing his job, is back in China and said he had no problem in organizing a debate two months ago about the problems with North Korea on Phoenix television, a satellite station based in Hong Kong that is shown on the mainland.

“North Korea will ultimately fail no matter how much you throw money at it, and it is in the process of collapse,” Mr. Deng said.

The heightened debate in China is spurred in part by fears that North Korea could collapse even though economic conditions in the agriculture sector seemed ready to improve, several Chinese analysts said. Indeed, one of the tricky balancing acts for China is how much to curtail fuel supplies and other financial support without provoking a collapse that could send refugees into China’s northeastern provinces, and result in a unified Korean Peninsula loyal to the United States.

If there’s anything that’s as difficult as reading the tea leaves out of Pyonyang, it is, of course, reading the tea leaves out of Bejing. Even in what is by all accounts a new, slightly more open era the Chinese leadership is notoriously secretive about its intentions and its attitudes, albeit not nearly as closed as the Kim regime. One of the few places one can look for clues to the debates that are likely going on inside the Chinese leadership are the official newspapers that are published out of Beijing, in no small part because it’s unlikely that we’d see something that calls official policy into question unless it was authorized. That’s what makes the article by General Wang, which appears to have been drafted before the news of the hacking of Sony’s computers broke, so interesting. The possibility that the Chinese may be losing patience with the regime in Pyongyang, something that seems to have become more of a public issue since Kim Jong Un rose to power in the wake of his father’s death, raises some rather obvious questions about the future of the Kim regime itself. By all accounts, if the Chinese decide to start withdrawing their support, economic and otherwise, then the collapse of the Kim regime wouldn’t be far behind. This is why, as has been the case for some time now, the real key to controlling North Korean behavior lies not in further economic or other sanctions, which at this point would have only a limited impact on a nation that is likely cut off from the rest of the world, but through Beijing and persuading the Chinese to use their influence with the Kim regime to put tighter control on North Korean behavior.

All that being said, it is likely best to view reports of Chinese “frustration” with Pyongyang with a grain of salt at the very least. For one thing, the reports noted above are all that different from reports that we’ve seen in the recent past. There were similar reports four years ago based on information contained in diplomatic cables disclosed by Wikileaks, for example, and then again in 2013 when the North Koreans began heating up tensions on the peninsula in advance of their eventual third nuclear test, a test which the Chinese condemned. Later, China was among those nations that pressured the Kim regime to return to the nuclear talks that had been abandoned some years earlier. Finally, just about a year ago, renewed reports about Chinese unease with the political situation in Pyongyang resurfaced in the wake of the news of the arrest and execution of Jang Song-Thaek, the uncle of Kim Jong Un who had long been seen as the second most powerful man in the country and was, by all accounts, China’s most reliable ally in the North Korean leadership. Despite reports earlier this year that North Korea was “on the verge of collapse,” though, and speculation during the late summer over the reasons behind Kim Jong Un’s prolonged disappearance from the official media in North Korea, the Kim regime has survived for another year and collapse seems unlikely in the near future.

Kevin Drum correctly points out what seem to be the two major factors influencing Chinese policy toward Pyongyang:

North Korea’s very weakness is also its greatest strength: if it collapses, two things would probably happen. First, there would be a flood of refugees trying to cross the border into China. Second, the Korean peninsula would likely become unified and China would find itself with a US ally right smack on its border. Given the current state of Sino-American relations, that’s simply not something China is willing to risk.

Not yet, anyway. But who knows? There are worse things in the world than a refugee crisis, and relations with the US have the potential to warm up in the future. One of these days North Korea may simply become too large a liability for China to protect.

Perhaps, but if that day comes, then I suspect that it will come in one of two ways. Either some other force inside North Korea, most likely the military, will rise up against the Kim regime and pull off the coup d’etat that everyone in the Kim regime seems to be afraid of the most. In that case, we’d likely see some form of liberalization inside the DPRK from the bizarre despotism that the nation has lived under since the end of World War Two, but we’d be unlikely to see reunification with the south any time soon, and the DPRK would remain a client state of China. The other alternative is that North Korea descends into chaos to such an extent that the Chinese send in the People’s Liberation Army to “restore order” and, of course, install a regime palatable to Beijing in the process. What China is unlikely to allow to happen, though, is an outcome that essentially extends the borders of the Republic of Korea, a close American ally of long-standing, to the Yalu River. Either of these events could happen very quickly, seemingly overnight and without warning, but when they happen is likely to be largely within the discretion of the Chinese government and, for the moment, they seem willing to let the status quo continue.

Doug,

I’m with you. I’ll believe it when I see it. Even so, I wonder when the DPRK will be seen as a liability for China? Sticking a thorn in our side can’t be that beneficial to China.

Rob,

At some point, it won’t be I assume. Kim and his minions are obviously expendable as far as Beijing is concerned. I get the impression that China’s main concern going forward would be having some say in the post-Kim status of North Korea.

Doug,

About a decade a go, when I went back to grad school and taught undergrads in economics, I used an article that discussed North Korea as a way to talk about how messed up communism is. Since the 1960s, North Koreans have lost several inches off their hight compared to South Koreans due to malnutrition. That’s one of the minor horrors that the Kim regime has visited upon those people.

Very sad.

Oh, and I agree: China doesn’t like instability. Even if it means maintaining a horror show like North Korea.

@Rob Prather: I kind of suspect the China views North Korea as a hobby. It’s not that expensive and it doesn’t have to make sense.

@Gustopher: I wonder how much of this stuff we’re seeing is actually political Kabuki carried on between two different groups in China….

If China ever decides they don’t want to indulge their local pet madman anymore, I expect a very quick squish.

I’d love to know whether there are any low-level, backdoor discussions going on with China re regime change in NK. I’d assume at a minimum the Chinese would want an iron-clad guarantee that US forces would not be stationed in the northern part of a united Korea.

I’m sure that China is not that bothered by having an evil neighbor. Having a crazy neighbor is more problematic. As the North Korean regime seems dependent on constant crisis and provocation to maintain itself, the odds that they will go too far and provoke more than China can tolerate. Worst case would be NK lobbing nukes at us and us lobbing more nukes back at them; not a good outcome for China (or anyone else, of course).

So I expect that China will tolerate Kim III so long as they think he’s not crazy enough to take those kinds of risks. There’s no way of knowing how long that will be.

“Either some other force inside North Korea, most likely the military, will rise up against the Kim regime and pull off the coup d’etat that everyone in the Kim regime seems to be afraid of the most.”

This. I think it’s likely that China’s long game is a transition that puts a more reliable puppet in charge. I would be surprised if they played any direct role, but I could certainly see them putting the conditions in place that would be conducive to such an outcome, and then letting things happen ‘of their own accord.’

At this point, it may not even have to be a coup though – AFAIK, Jong-un’s health is pretty bad, so it may just be about influencing whichever member of the extended family is most likely to consolidate power after Jong-un’s death. Of course, China would still have to worry about that person getting purged in the meantime . . .

@michael reynolds:

I would be curious as well.

In the end, I’d be surprised if it was the case only because I think the risks for the Chinese would vastly outweigh the benefits. Sure, the US would love to know what China’s plans for the DPRK are, but I don’t think there is any reason for China to let us in on their intentions, and there are plenty of good reasons to keep the US in the dark.