Chinese Perestroika?

United Press International: fading fear in Chinese life

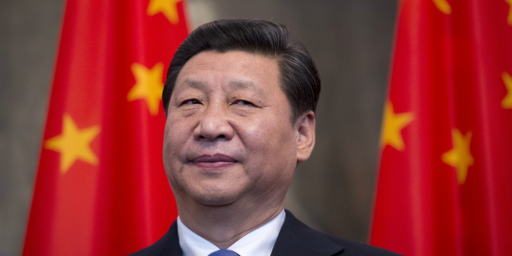

Has last year’s leadership change produced a kinder, gentler China? The duo of President Hu Jin Tao and premier Wen Jia Bao, with their “people first” policies, is threatening to undermine traditional Chinese fear of, and obedience to, authority.

It’s already a break in tradition that the leaders are referred to as “Hu and Wen.” One did not speak of “Mao (Zedong) and Zhou (Enlai)” or “Deng (Xiaoping) and Li (Peng)” or even “Jiang (Zemin) and Zhu (Rongji).” A single strong figure of authority was always paramount at the center — until now.

The term “qin min,” roughly translated as “people first,” describes the new leaders’ populist approach, as demonstrated when Wen visited a small village over Chinese New Year, dropping in on a peasant family to share their traditional dumplings, and when Hu, on a visit to the countryside, ordered immediate payment to a farmer who complained of unpaid wages.

Most people seem to be impressed with the new approach. At the same time, they are starting to test the waters, to see just how far the official benevolence extends.

Over the past 15 years, the Chinese people have come to enjoy much economic freedom. The crackdown on the democratic movement of 1989 warned people away from politics, while relaxed economic policies diverted their attention to making money. But access to information, growing economic strength and increased exchanges with the outside world all contribute to a sense of empowerment.

China may remain on the world’s human rights watch list, but freedom of expression and of action are on the rise. The wall of fear that used to restrain people’s behavior is coming down, with the exception of certain sensitive political issues that still push the Communist Party’s buttons.

“Access to information makes it impossible to control people’s minds,” media commentator Sun Lichuan told United Press International.

He believes that once Chinese taste economic freedom, they will demand more social liberty.

Indeed.

Many Chinese are now speaking their minds. Scholars are extensively quoted in the media on social issues. Ordinary people chat freely, without fear of repercussions. In a casual conversation with his passengers on a late afternoon in January, a Beijing taxi driver dared to broach a forbidden topic, the banned Falun Gong movement.

“Falun Gong?” he said, “I think the crackdown on them was because, in their own way, they made noise about government corruption.”

Such statements were rare in the past.

The present environment is not entirely attributable to the new leadership; the fear of authority has gradually diminished over the past decade. But the tone in which people refer to the government has shifted, from the awe and fear in which people held Mao and Deng, through an era of irreverence toward Jiang, when jokes denigrating the government were popular, to the friendly rapport that people feel for Hu and Wen. Last spring when severe acute respiratory syndrome hit China, messages such as, “Hang in there, Brother Hu,” appeared on the Internet.

How much liberalization can society sustain, however, under Communist Party rule? The new openness has bred a steady stream of intellectuals quietly but unyieldingly demanding democracy. Among Beijing’s intellectual elite, for example, an unpublished book has been circulating, commemorating the late scholar Li Shenzhi, a former vice president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and a longtime democracy advocate. Li once publicly criticized Chinese intellectuals for backing down after the crackdown on Tiananmen Square democracy activists.

Chinese are now more resilient, even in their pursuit of freedom. The last decade has seen the sharp rise of nationalism in China. The support and love of country carry a corollary: It’s OK to make demands under the banner of patriotism.

My knowledge of Chinese politics is exceedingly limited, so I tend to view this through Cold War lenses. To the extent this analysis is correct, it reminds me very much of the Gorbachev days in the USSR, when he instituted glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) to try to save Soviet communism by making it more viable but wound up hastening its collapse. My guess is it won’t happen quite so quickly in the PRC, where free market economics have been gradually taking hold for a quarter century or so.

Let anyone threate the continuance of their regime and the hammer will come down just as severely as in the past. Garunteed!